It was the best of tributes, it was the worst of tributes: The statue Charles Dickens never sought

The great author was clear that he didn't want a statue of himself, but his wishes were ignored last week. Proof, if any were needed, that the future has a life of its own

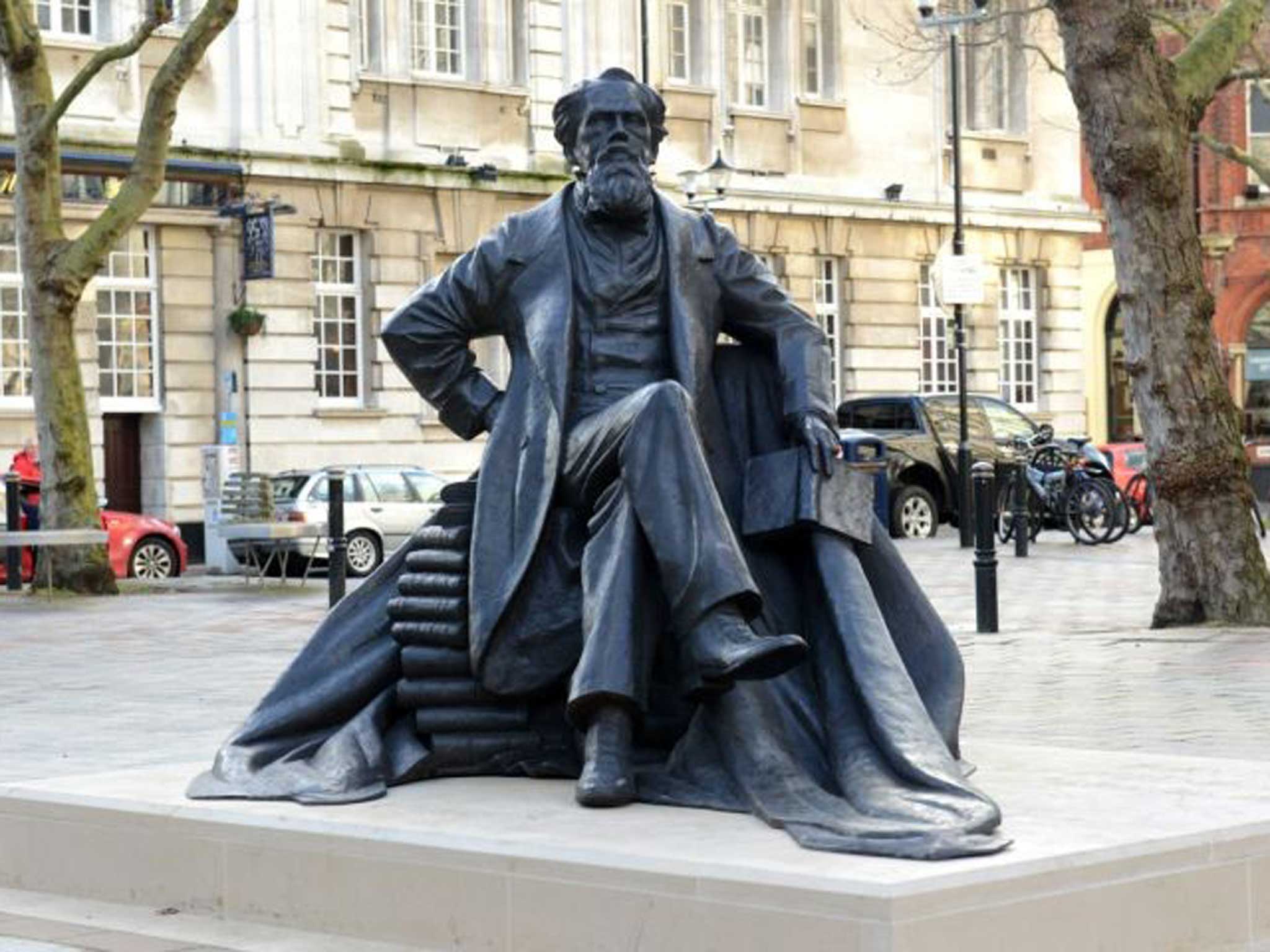

It is not very often that a public memorial to one of the great heroes of British literature provokes any kind of controversy, and yet the unveiling on Friday in Guildhall Square, Portsmouth – his childhood home – of a statue of Charles Dickens stirred a faint whiff of spectatorial unease.

It was not that anyone who could conceivably have taken an interest in the scheme was upset: the council appeared to be delighted by its new amenity and Dickens' great-great-grandson remarked: "There are so many facets to capture – a great author, a social reformer, a man with fantastic energy and charisma … the sculpture has all that and more." No, the real problem had to do with the wishes of the subject.

Dickens' instructions to his heirs, it turned out, were dead against whatever plans might be cooked up by grieving friends to make him the focus of "any monument, memorial or testimonial whatsoever". The Dickens family, not unreasonably, takes the view that this proscription was designed to forestall one of those exercises in toga-draped mock-classicism that rest upon many a Victorian plinth, and could be safely disregarded.

But at the very least Martin Jennings' 1.7m (5ft 6in) bronze, replicated from the original clay, raises some awkward questions about the wishes of the great and good when it comes to posthumous re-imaginings of them and quite how punctiliously their instructions should be followed.

Happily, Dickens stopped short of proscribing a biography: this was completed soon after his death by his fast friend John Forster, and, not surprisingly, contained nothing that was likely to embarrass his descendants. The revelations about his relationship with the young actress Ellen Ternan would have to wait for the sleuth-hounds of the 20th century.

But many another literary titan has set his, or her, face against posthumous commemoration. Dickens's great rival William Makepeace Thackeray, for example, instructed his daughters to ensure that there shall be no book about him "when I drop", while George Orwell expressed the pious hope that no biography should ever be written.

Naturally enough, the publishing industry and human curiosity being what they are, these fiats were very soon ignored. There have been at least three full-length modern treatments of Thackeray, and as many as six of Orwell. I have written one of each myself, with no qualms whatever.

Theoretically, the knowledge that you are embarking on a book in defiance of the person whose spirit hovers above it ought to be a source of disquiet. In practice, doubts of this kind seldom disturb the biographer's conscience. My own view is that if you aspire to the status of a public figure, whether in the arts or any other branch of human activity, then you should not be surprised if the public takes an interest in you. Neither, in the interests of objectivity, should you attempt to suppress or manipulate its search for data. Thackeray himself acknowledged this widespread fascination with the personalities behind art when he remarked that "all I remember of books generally is the impression I get of the author".

More even than this, biography is usually – though not infallibly – at least an indirect route into the creative heartland. Without it our appreciation of a writer's achievement lacks a vital dimension. There is, for instance, a scene in 1984 in which Winston Smith, hauled into a crowded cell at the Ministry of Love prior to his interrogation, hears the tele-screen admonish a fellow-prisoner who is trying to slip contraband food to a starving man. "Bumstead! 2173 Bumstead J! Let fall that piece of bread" shrieks the disembodied voice. It takes a knowledge of Orwell's early life in the Suffolk coastal town of Southwold to confirm that this was the name of the local grocer, and that, even here in the nightmare world of totalitarian Oceania, Orwell is glancing back to the world he had known a decade and a half before.

Inevitably, the creative artists who go to their deaths instructing admirers to leave the grave undisturbed are more or less guaranteeing that these orders will be gainsaid, if only because they themselves will not be there to defy the resurrectionists. Much more liable to succeed, consequently, are instructions to obliterate physical artefacts.

There was a tremendous row several years ago when various Kafka letters that were supposed to have been destroyed were released into public view. Similarly, Philip Larkin's last request to his secretary at the University of Hull was that she should burn a stack of his diaries. This she did, in an act of duty which most biographers would probably regard as excessive. Certainly, the diaries might not have revealed their author to be a particularly nice man, but whatever the exact nature of their contents, Larkin presumably used them either to express various ideas about the person he thought he was or, alternatively, to project various fantasies about the person he might have liked to be, and their destruction leaves a part of him hanging tantalisingly in the ether.

At the same time there are other reasons why the Dickens-Larkin line ought to be stoutly resisted. At bottom, thinking that you can manipulate or otherwise influence the future according to your own dictates is a kind of vanity. Victorian novels, including those by the author of Great Expectations, are full to bursting point with dreadful old tyrants grimly ruining the lives of their children by stuffing their wills with clauses designed to frustrate unsuitable marriages or tie up capital in ways acceptable to the deceased.

One of the great lessons of modern life, on the other hand, would seem to be that the future, much like the past, has a life of its own. No amount of public relations exercises or outraged signalling from beyond the grave stops a determined biographer from succeeding in the end, and a refusal to play the game – see the case of J D Salinger – is nearly always a way of stirring up trouble for your reputation.

To return to the case of the monument lately erected in Portsmouth – Dickens himself was a practised manipulator of information about his own existence: the fragrant air of his Gad's Hill garden was several times polluted by smoke from the bonfires of burned papers, set ablaze as a means of keeping future biographers off the scent. One might even think that Martin Jennings' sculpture is a long overdue additional payment designed to improve the bargain established between Dickens and his public in that public's favour, that after long years of Dickens deciding what he will give us, we have finally settled on something that we want from him.

And in Mr Jennings' further defence, it has to be said that his representation of the great man is a remarkably good likeness. It might usefully be compared with the current BBC film of Dickens' dealings with Ellen Ternan, which, judging from the previews, has no hard-and-fast basis in historical reality at all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies