At least Di Canio is honest about his fascist views - unlike his critics

Our risk-averse culture becomes less tolerant of dissent each week

Because sport is now such an important part of national life, both in itself and as a metaphor for this or that, the appointment of a controversial Italian as manager of a Premiership football club has become something of a news story.

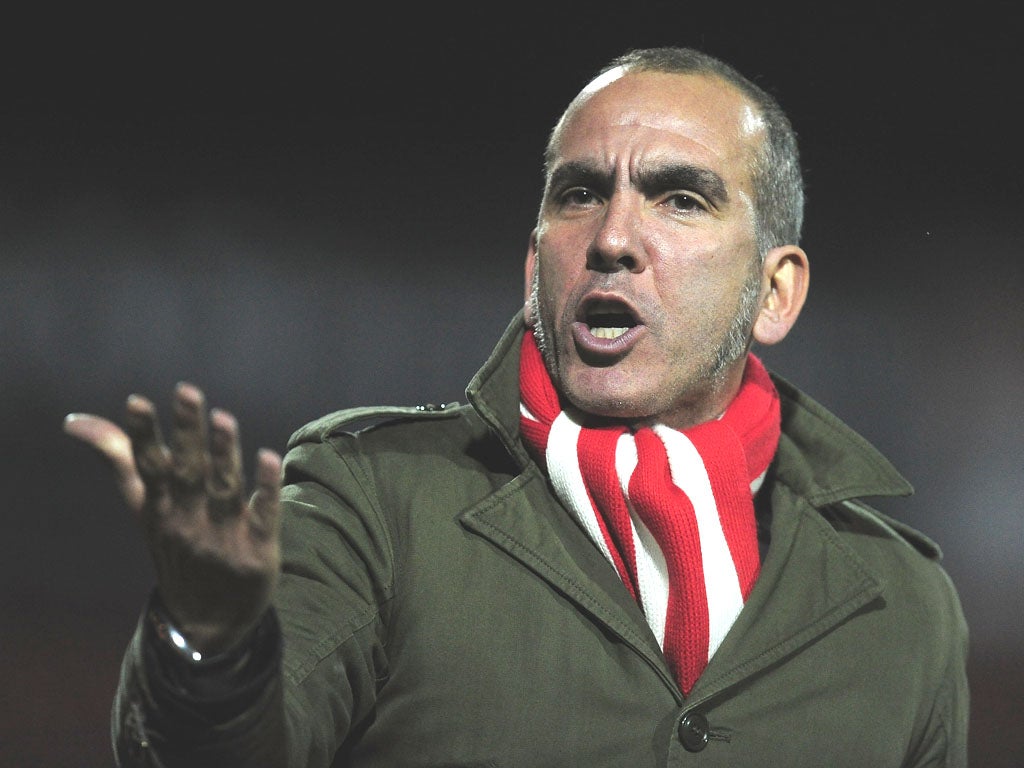

Already, it has caused a high-profile resignation from the club’s board and much rage and hand-wringing in the press and online. The background, personality and, above all, opinions of the new Sunderland manager, Paolo Di Canio, transcend the small matter of football, apparently.

There certainly seems to be a number of good reasons to be offended by his appointment. He is an awkward, shouty character, whose histrionics as a player – pushing a referee over, going on sit-down strike on the pitch – are better remembered than his achievements. His style as a boss is “management by hand grenade”, according to his former employer. He is somewhat boastful, proud of his own egotism. His political views are a bit of a problem, too. In his autobiography, Di Canio wrote that Mussolini was a “deeply misunderstood individual... His actions were often vile. But all this was motivated by a higher purpose.” He has described himself as a fascist and more than once was photographed, mad-eyed, raising his right arm in the direction of fans during games in Italy.

Although he has always denied being racist, and his writings in the Italian press bear out this claim, the fact is that it is fans on the far right who continue to taunt and bully black players across Europe.

Questions have been asked. Is this the sort of man we want in public life? What kind of example does his appointment set to young football fans? Were other, less controversial candidates not available?

It is, in fact, the reaction to Di Canio’s appointment which has been interesting. The club’s former vice-chairman, David Miliband, swiftly moved to distance himself from the club, resigning from the board. Local MPs have spoken of boycotting games. Grizzled, man-and-boy fans have been incandescent. “It is not my club any more,” one has written. “The heart has been ripped out of it.”

We have become so inured to intolerance masquerading as a sense of social responsibility that we have become used to this kind of thing. The idea that a person with unacceptable views, however seriously or privately held, should as a result of those opinions be denied a high-profile job is widely held by people of conscience.

Yet is this not, in its quietly sinister way, itself a form of fascism? Freedom of thought and speech is only meaningful if it applies to those who have opinions which the majority find unpalatable. The argument that only those in the political mainstream are appropriate as football managers is a small step from a wider kind of control. It is part of the same spectrum as, say, a government minister demanding the sacking of a columnist who expresses a view with which she disagrees, or a social services department denying a couple who support Ukip from adopting a child.

Our queasily risk-averse culture becomes less tolerant of any kind of dissent week by week. It is no longer enough to disagree with someone who holds inappropriate views; that person should be banned, barred, cast into the outer darkness.

It is a fear of difference, perhaps even of individuality, that is at work here. Group-think, the kind of achingly concerned, safety-first attitudes which emerge in committees, conferences and boardrooms across the country, is above all self-protective. It wants everyone to be as decent and circumspect as the majority of respectable citizens.

This socially legitimised form of prejudice tends to be highlighted by the cartoonish extremes of professional football. Any player or manager who dares to express opinions about the wider world – Graeme Le Saux, Joey Barton and Paolo Di Canio – will find himself the subject of mockery and sneers. More widely, it tends to drain the colour from everyday life, to reward cautious mediocrity, and to reveal a society afraid of itself.

Beyond the misery memoir

There are few, if any, bad books of mourning. When John Bayley wrote about the illness and death of his wife Iris Murdoch, he was praised for his affectionate honesty, with only a few critics raising questions of taste or morality.

The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion’s anguished memoir following the death of her husband John Gregory Dunne became a classic of remembrance, and Joyce Carol Oates’s A Widow’s Story was praised as a moving response to the many letters of condolence which she had received.

No doubt Julian Barnes’s new book, Levels of Life, which closes with the death of his beloved wife Pat Kavanagh, will be as clear-eyed, perceptive and sad as anything he has written, and fully deserving of the lead reviews it is getting.

It is the job of serious writers to invade their own privacy sometimes, and the best of these books will bring comfort and wisdom to readers. It must be my repressed English nature which makes me feel slightly uneasy about this new literary trend, the mourning memoir.

Twitter: @TerenceBlacker

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies