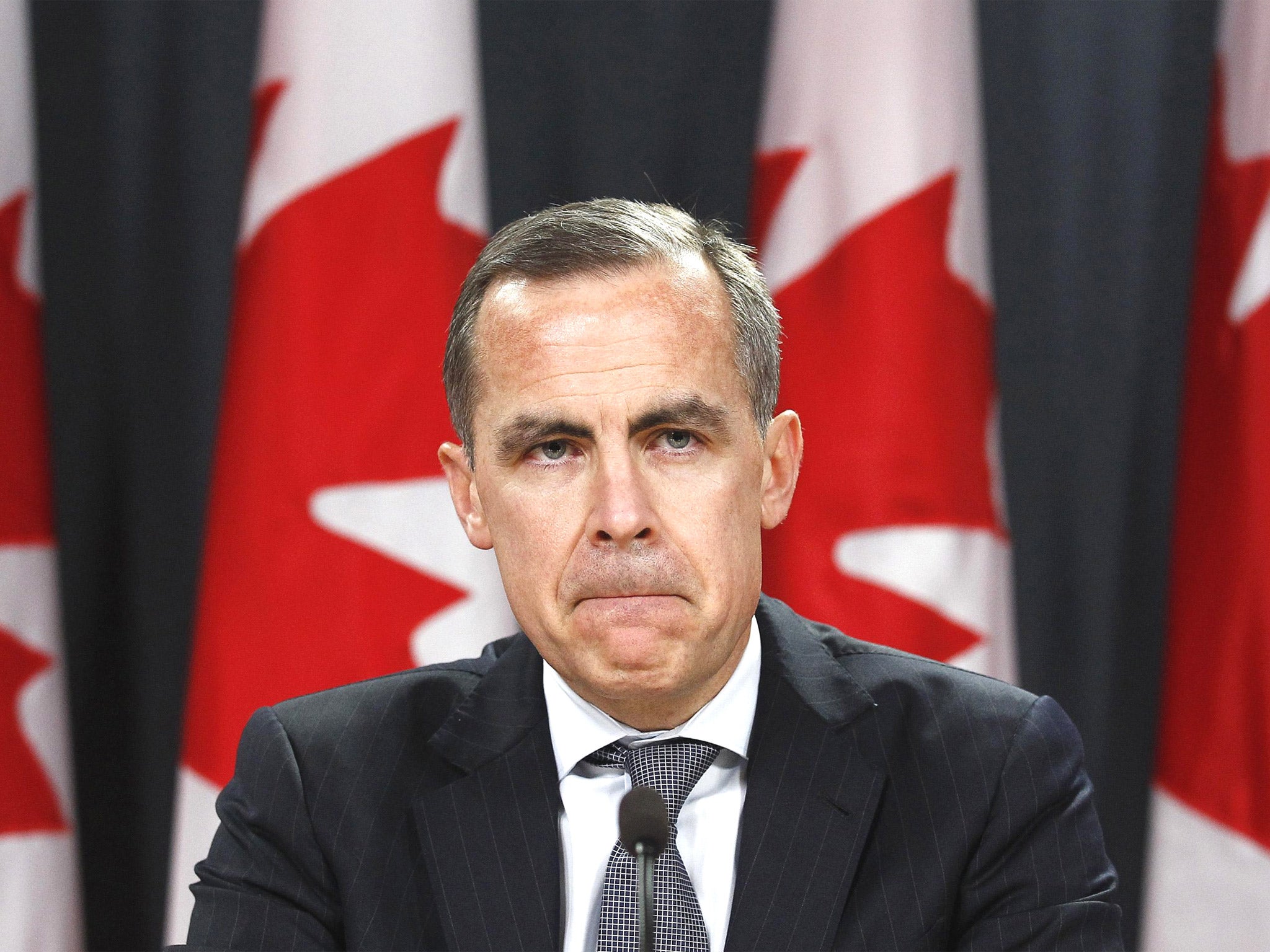

Mark Carney's selection for the Bank of England is related to his being competent, not Canadian

Our Chief Economics Commentator on why George Osborne wanted someone who could earn the trust of savers, both here and across the world

If it seems strange that we should look abroad for someone to run our central bank, it is all the more strange that there are some nationalities that feel a natural “fit” and others that don’t. A Canadian or an Australian feels fine, but it would be unthinkable to have a German or an Italian running our central bank – notwithstanding the fact that Germany has had a much better post-war inflation record than the UK has and an Italian heads the European Central Bank.

So there is something deep about central banking that makes it different from, say, commercial banking or motor manufacture. What is it? I think the answer lies in its evolution. The original purpose was to enable governments to fund themselves more cheaply: the Bank of England was founded by a group of City merchants in 1694 to raise money for William III to finance wars. Put bluntly, an independent bank was trusted more than a national government. Its other functions, such as control of the money supply, supervision of the banking system and so on, gradually evolved from that. But that original role, raising money, remains as important now as it was then, as the UK government (and the US, though not the Canadian) must borrow more now as a proportion of GDP than ever before in peace time.

So we need a Bank of England, and a Governor, both trusted by the government but also by the country’s savers – indeed by savers anywhere in the world. This mixture of independence but also a national purpose would be hard to sustain were the Governor not someone of the same broad cultural heritage. I suspect much of the problem that Germans have with the euro is that while the ECB is based in Frankfurt and headed by someone who is technically extremely able, the currency is controlled by people outside the German tradition. That the ECB has proved the most competent of EU institutions is not enough to win it broad support from the German people, a majority of whom would like the deutsche mark back.

Central bankers are not elected, and the relationship between them and a democratic government must always place governments first. In 1926, Montagu Norman, the then Governor of the Bank of England, put it this way: “I look upon the Bank as having the unique right to offer advice and to press such advice even to the point of ‘nagging’; but always of course subject to the supreme authority of the government.”

That fundamental point still holds, of course, but the relationship between central banks and governments has changed over time. For much of the post-war period, the central banks were more subservient than they had been in, say, the 1920s. They could “nag” but governments took little notice. The catastrophic inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s changed all that. As a result, in the past 20 years, their power has tended to increase. The independent role of setting interest rates that the Labour government gave the Bank in 1997 was part of a broader international shift. Labour’s other innovation, taking away banking supervision, has now been reversed, making the Bank more powerful than at any stage since the Second World War.

Add to this the experience of the past few years, which have seen a failure in monetary policy as well as fiscal policy – Canada did not have a housing boom and bust on the scale we did – and you can see why the job matters. You can also see the complexity, because the Bank has to oversee what is still the world’s largest international financial centre, as well as all the UK functions. Does hiring a culturally attuned outsider mean the Bank will perform better? Well, it is a start.

Balancing the books is nigh on impossible

A week to the Autumn Statement, the pre-Budget report, and with the confirmation of the GDP figures yesterday all the information is in. The background is that the deficit reduction plan is stuck. The deficit is rising, not falling, because of a shortfall in tax receipts. This matters because if it continues, we need to know why. Slower than expected growth is one thing; if it is structural weakness in our tax system, that is something else.

The next thing that matters is what the Chancellor does about it: roll back the programme, cut more, or increase taxation? The final thing that matters is the longer-term direction of fiscal policy from the Office for Budget Responsibility. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has done some chilling calculations of the funding gap in the longer term, which amounted to a rise in VAT to 25 per cent.

The harsh truth is that voters demand more than they are prepared to pay for in tax. And the rest? Unless I have missed something big, it will be mostly noise. And reflect on this. Not only would Labour have done much the same; it may well end up doing so in another two and a half years’ time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks