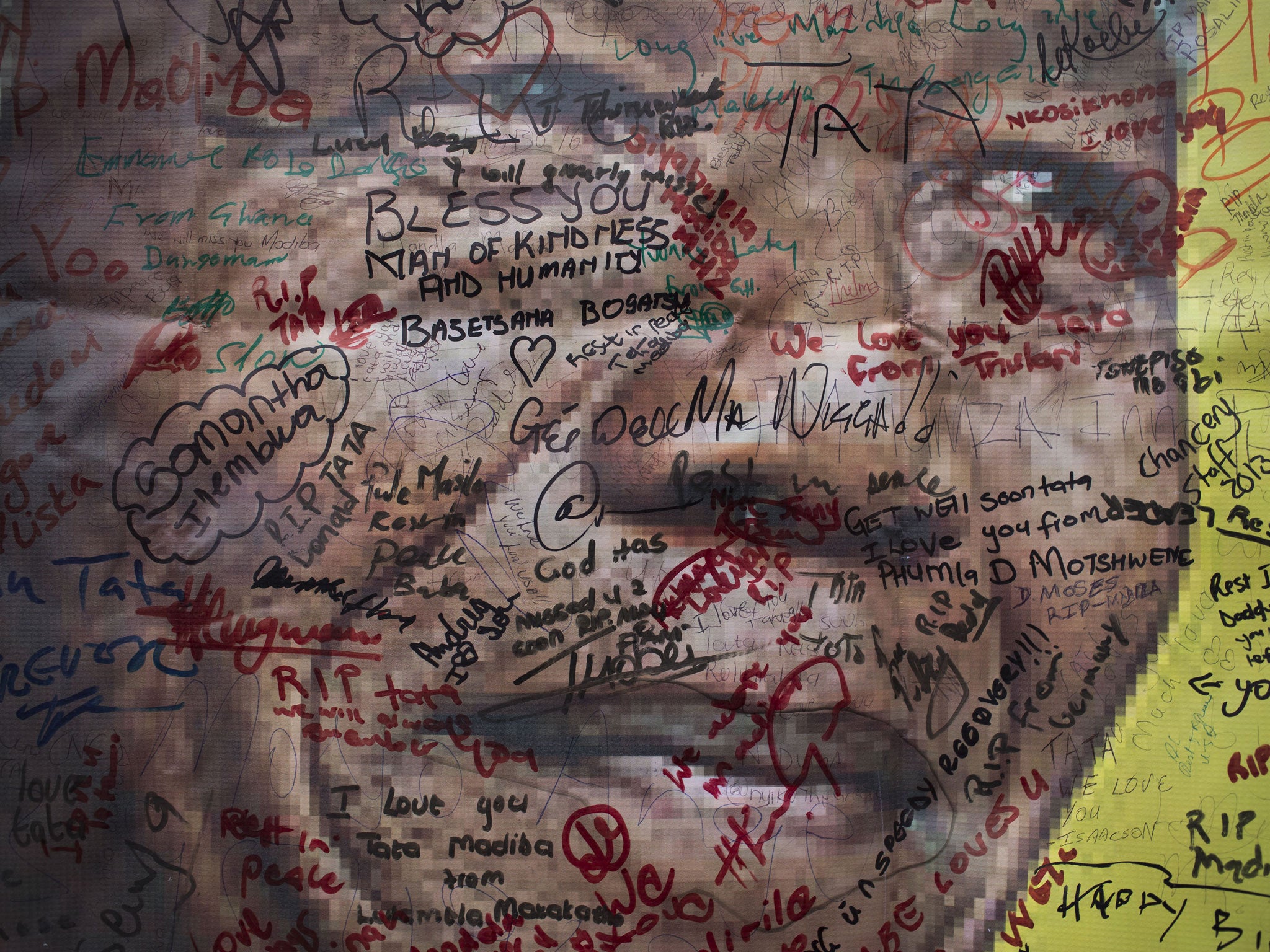

Nelson Mandela: To black South Africans, he was like a father caring for his children

Mandela gave hope to the victims of apartheid even in its very darkest days

At various times over six decades I have received many pieces of sad news, of many kinds. The news of the death of Nelson Mandela joins many of them in a kind of equality of sadness. Known for proclaiming his ordinariness, he might have understood my reaction. A human being has passed on. It is his humanity I choose to remember at this time.

Young people the world over ordinarily sense the environment of their upbringing without understanding its larger implications. As consciousness of themselves and their world expands, the memories of their childhood transform into knowledge that connects them with a broader community of purpose. If you will, call it a nation.

I was too young to be aware of the full implications of the Treason Trials in the late 1950s in which Nelson Mandela was one of the accused. But I do have a clearer memory of the potato boycotts of 1959, in which black people protested against potato slave farm conditions in Bethal. I was 12 years old when I heard about people killed at Sharpeville in 1960. One memorable utterance, by my maternal grandfather, embossed the event in my mind permanently.

He was a priest of the Presbyterian Church of Africa in Bloemfontein, a world away from our small township of Charterston, in Nigel, 33 miles east of Johannesburg. Unexpectedly, he dropped in on us in the darkening twilight of that fateful day, 21 March 1960. He found me alone at home. What does a boy do to welcome a tall, formidable man with a deep, stentorian voice?

My mother was away somewhere in the township delivering babies. My father was even further away as an inspector of schools.

Grandfather welcomed himself to my home, and found his way to the living room, while I peered into the gathering darkness for a candle and match-box. Just then, I heard the radio in the living-room crackle. The Big Ben chime followed announcing the seven o’clock news from the South African Broadcasting Corporation.

That night, I discovered something in common between my father and grandfather. It was the way they listened to the news bulletin. They responded with lusty commentary to various news items. My father’s running commentaries would reach us in the kitchen. Sometimes we heard a long whistle of sheer consternation. Sometimes he denounced “the damned Dutch”, as he and some of his friends referred to Afrikaners; sometimes he exclaimed in despair and resignation: “Hhai!” With each comment we weighed the impact of what he heard. The news, it was clear, was seldom pleasant.

“Fifty-seven dead!” my grandfather’s voice boomed from the living room. It must have been the tally at the time of the shootings at Sharpeville where black people had gathered in protest against identity documents by which a hostile state controlled their movements. I stayed with the figure of 57 until I learnt much later, at high school in Swaziland, that as many as 69 people were shot dead and 300 injured.

My father decided to send me to Swaziland, to St Christopher’s Anglican High School, in 1961. In 1953, the white Nationalist government had passed the infamous Bantu Education Act to make way for an inferior education designed for black people. There were many like my father, who took similar decisions for their children.

It was at St Christopher’s that my childhood impressions of the world took on the contours of understanding, as my consciousness broadened. It was there the anger, consternation, denunciation, and despair that I read from my father and grandfather’s reactions to the news became my own. It was there also that Nelson Mandela wandered into my full awareness, in a way I could never have imagined. The legendary politicians who were Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu suddenly came across as fathers. They too took decisions for the future of their children, similar to those my father took. Two of Mandela’s sons, and two of Sisulu’s, joined us at St Christopher’s, in 1962 and 1963 respectively. Their daughters, similarly, went to St Michael’s Anglican School in Manzini. My peers and I became witness to the personal impact of large events, and experienced the unfolding of history.

I remember that a picture of Nelson Mandela with Ben Bella of Algeria circulated through the school. The Black Pimpernel, as Mandela was known at that time, had skipped the country clandestinely to establish the military wing of the ANC as a signal for the abandonment of peaceful protest and the beginning of the armed struggle. As he travelled across Africa and beyond, Nelson Mandela took us along with him across the world. The anti-colonial struggles in Africa and Asia entered our consciousness, there to remain.

And so each world event, each major national event, has its many invisible personal significances. Many such events over time link individuals to others in ever expanding communities of common purpose. That purpose was to achieve freedom for black people in South Africa and the world over. We sensed it and lived it.

As Nelson Mandela bows out of the world and becomes billions of memories, I think of 12-year-old South Africans today. What do they make of what they hear on radio or see on television? What did they make of Mandela family battles over parts of his estate while he was alive?

What do they make of Mandela’s willingness to stand trial if the law so required, when current day politicians enter high office with a long list of criminal allegations? What do they make of entering the exam room to find the question papers were not delivered?

“Thirty-four dead!” my grandfather would have exclaimed 52 years later as last year’s shootings of miners at Marikana were announced, in the land of freedom where a constitution and the rule of law were designed to make massacres less likely.

A 12-year-old grandchild listening to him would feel less an emotion of outrage than a sense of moral confusion: a childhood intuition seeking comfort and guidance, but sensing little. A moral compass that embodied a transcendent purpose may have definitively passed on. There will be no point in looking for it in another individual. It will more likely be found in the voices of reawakened citizens.

Njabulo Ndebele is Chancellor of University of Johannesburg

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks