"The past," the novelist L P Hartley remarked in the opening lines of The Go-Between, "is a foreign country. They do things differently there." Nowhere is the recent English past more of an alien territory than in the world of 1970s politics, where deviations from the norm abounded, "personalities" stalked the Westminster corridors like so many late-Victorian raree showmen and – as nearly always happens when politics turns over-dramatised – scandal threatened on every side.

Nearly all these tendencies, it has to be said, are reflected in the bright, dazzling but then irrevocably soured and in the end tragic career of Jeremy Thorpe.

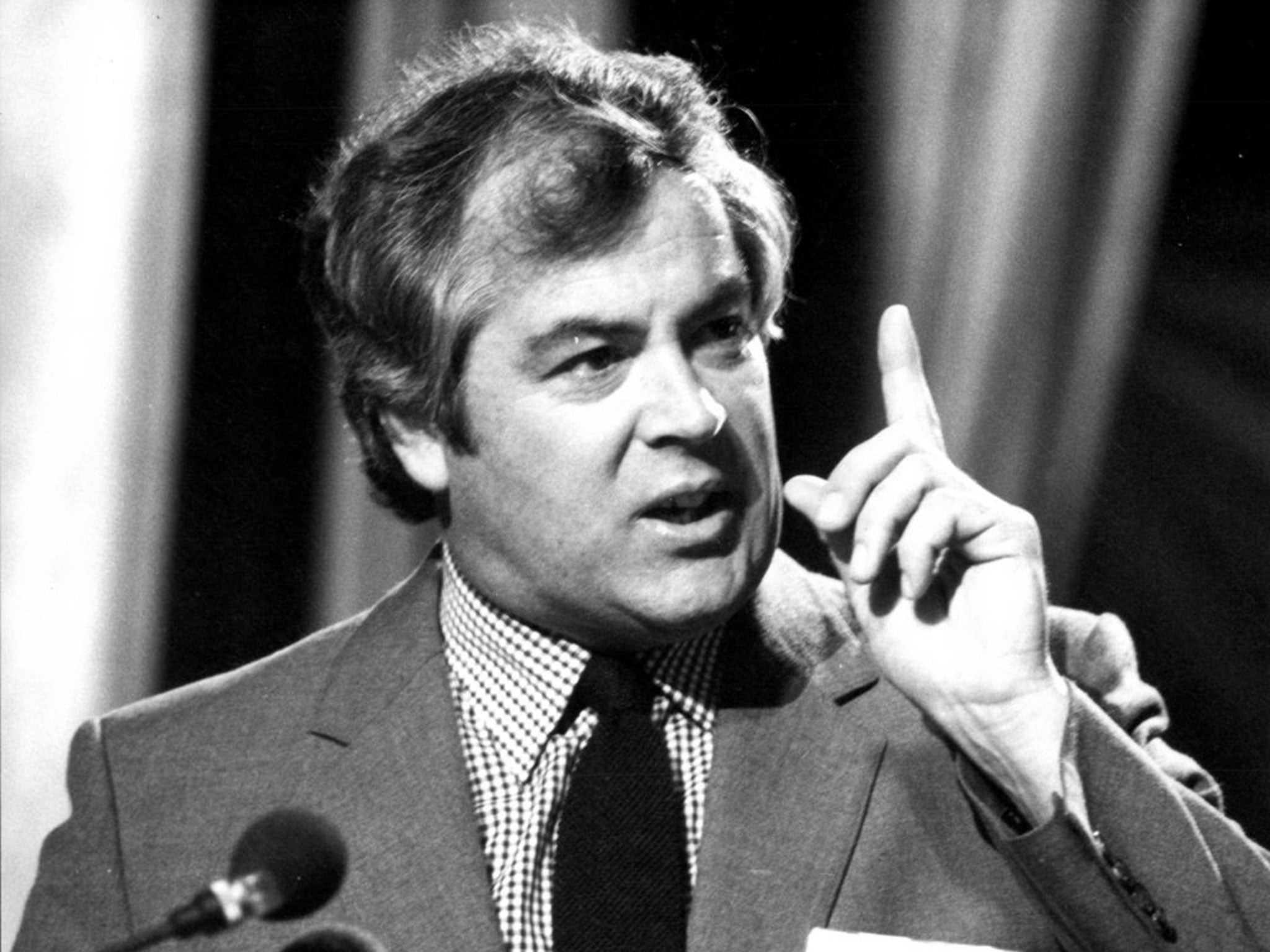

It says something for Thorpe's Icarus-like flight to somewhere very near the summit of British politics – he might have been home secretary in 1974 if he could have carried his activists with him – and equally rapid descent into twilight that the news of his death, at the age of 85, was greeted with a certain amount of puzzlement. Not unreasonably, many observers, ignorant of his long, Parkinson's-assisted decline, assumed that it had already taken place. As I was a politics-obsessed Seventies teenager, on the other hand, the pictures of Thorpe's oddly cadaverous face and the curious trademark hat in which he liked to be photographed (à la Enoch Powell) brought back two distinctive, print-based memories.

The first was a feature run by the Daily Mirror shortly before one of the general elections of 1974 in which three newly enfranchised 18-year-olds were asked how they intended to cast their vote. The first, a bespectacled male swot, declared that he was voting Conservative on the basis of what he had read. The second, a cheery-looking lad in a bobble hat opted for Wilson on account of his nan – "she's Labour mad". The third elector, a girl, plumped for Thorpe as she found him "rather attractive". All of which, to this as yet unenfranchised teenager, seemed to cast grave doubts on the wisdom of allowing the vote to 18-year-olds at all, if at least two of them came out with this kind of rubbish.

The second was Auberon Waugh's election address to the electors of North Devon, issued shortly after Thorpe's acquittal on a charge of conspiracy to murder his putative former boyfriend Norman Scott and shortly before Waugh stood against Thorpe on behalf of a single-candidate pressure group called the Dog Lovers' Party. An injunction having been granted, this document, printed in The Spectator in lieu of Waugh's weekly column, was instantly recalled, but not before a few copies had made it to the Norwich branch of WH Smith. "The spirit of Rinka is not dead," Waugh concluded, in reference to Scott's slaughtered Great Dane. "Vote Waugh. Vote Dog Lover. Woof woof."

George Orwell once wrote that the British aristocracy as represented in Dickens's novels amounted to "a casebook in lunacy". The British Liberal Party, as headed by Jeremy Thorpe in the 1970s, amounted to a casebook in the deepest-dyed eccentricity. To Thorpe himself, with his hats and his sexton's smile and his depredations, by helicopter, on the Devon beaches, could be added the gargantuan figure of Cyril Smith (his child-abuse not yet exposed), the former television personality and celebrity chef Clement Freud, and such loose cannons as the exuberant Cornishman John Pardoe, with whom the former Labour chancellor Denis Healey was forced to consult in the wake of the 1977 Lib-Lab pact, remembered by Healey as totally irresponsible "in the literal sense".

By any measure it was an extraordinary collection of people, a kind of music-hall act masquerading as an alternative shadow cabinet, an activist's dream in which elements of showbiz, the PR stunt and genuine engagement with the issues of the day uneasily contended, and less flamboyant politicians such as David Steel and Alan Beith tended to look rather lost: the apparent relief with which, in the post-Thorpe era, Steel set about forging an alliance with the SDP and getting down to serious politics was rather marked. And yet in the wake of the murder trial and Thorpe's defeat at North Devon (Waugh obtained 79 votes and considered himself vindicated) it tends to be forgotten quite how much Thorpe achieved in his years as a party leader and, more important, quite how prefigurative that achievement was.

Back in the 1950s, Ronald Searle and Geoffrey Gorer produced a book of character sketches entitled Modern Types. One of them featured a Liberal parliamentary candidate. The text, beneath Searle's drawing of a painfully earnest-looking man addressing a solitary onlooker from a soapbox, read simply: "At parliamentary elections Mr X stands in the Liberal interest. He always loses his deposit. Fortunately he can afford to do this." At the time this was fair comment, for Britain between the 1930s and the 1960s was effectively a two-party state in which the Liberal vote hovered at around a million; five of the party's half-dozen seats in the Fifties were maintained via alliances with local Conservatives, and the Bloomsbury diarist Frances Partridge's attempts to vote Liberal in the 1945 election are represented as a thoroughly quixotic act.

By the 1974 elections, on the other hand, the share of the vote achieved by the two major parties fell below 80 per cent – an ominous foreshadowing of the current political kaleidoscope in which the party which emerges with the greatest number of seats next spring may achieve only a third of the popular vote. As to how Thorpe achieved this opinion shift (six million votes in February 1974), if part of it was attributable to straightforward dislike of existing arrangements, then another part was due to his charisma, a carefully stage-managed exercise in political placement that allowed this thoroughly establishment figure (barrister, Old Etonian, aristocratic second wife) to present himself as a maverick.

Much was made in Thorpe's obituaries of his mother's remark that it never occurred to him that anyone wouldn't be pleased to see him. Seen in retrospect, his early 1970s career makes him resemble a financier in a novel by Trollope or H G Wells – conscious that bankruptcy is looming but at the same time somehow not able to believe that the rug is about to be pulled. One of the many paradoxes of Thorpe's political life is that such a flamboyant operator should preside over a reawakening of the old non-conformist political tradition, a strain in British politics that seemed to have been cannibalised by Labour almost since the days of Lloyd George.

At the same time, there was nothing paradoxical – outside economics, anyway – about Thorpe's political stances. Unlike most of the contemporary politicians who assemble under this banner, he was a genuine liberal, who really did believe in such abstractions as pluralism, diversity and tolerance, rather than adopting the modern liberal default position, which is to say that you believe in all these things, while quietly sneering at those who neglect to follow the approved "progressive" line.

No doubt a government led, or colonised, by Thorpe and his henchmen would have been a disaster. But he would probably have sympathised with Miss Callendar, in Malcolm Bradbury's The History Man (1975), who, asked by the tail-chasing Professor Kirk to state her intellectual position, offers merely that she is "a 19th-century liberal". "You can't be," Kirk sniffs. "There are no resources." "I know," Miss Callendar returns, "that's why I am." Take away the sleaze, the vanity and the hubris, and what remains, at any rate in political terms, is a legacy many a debased modern operator would be glad of.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies