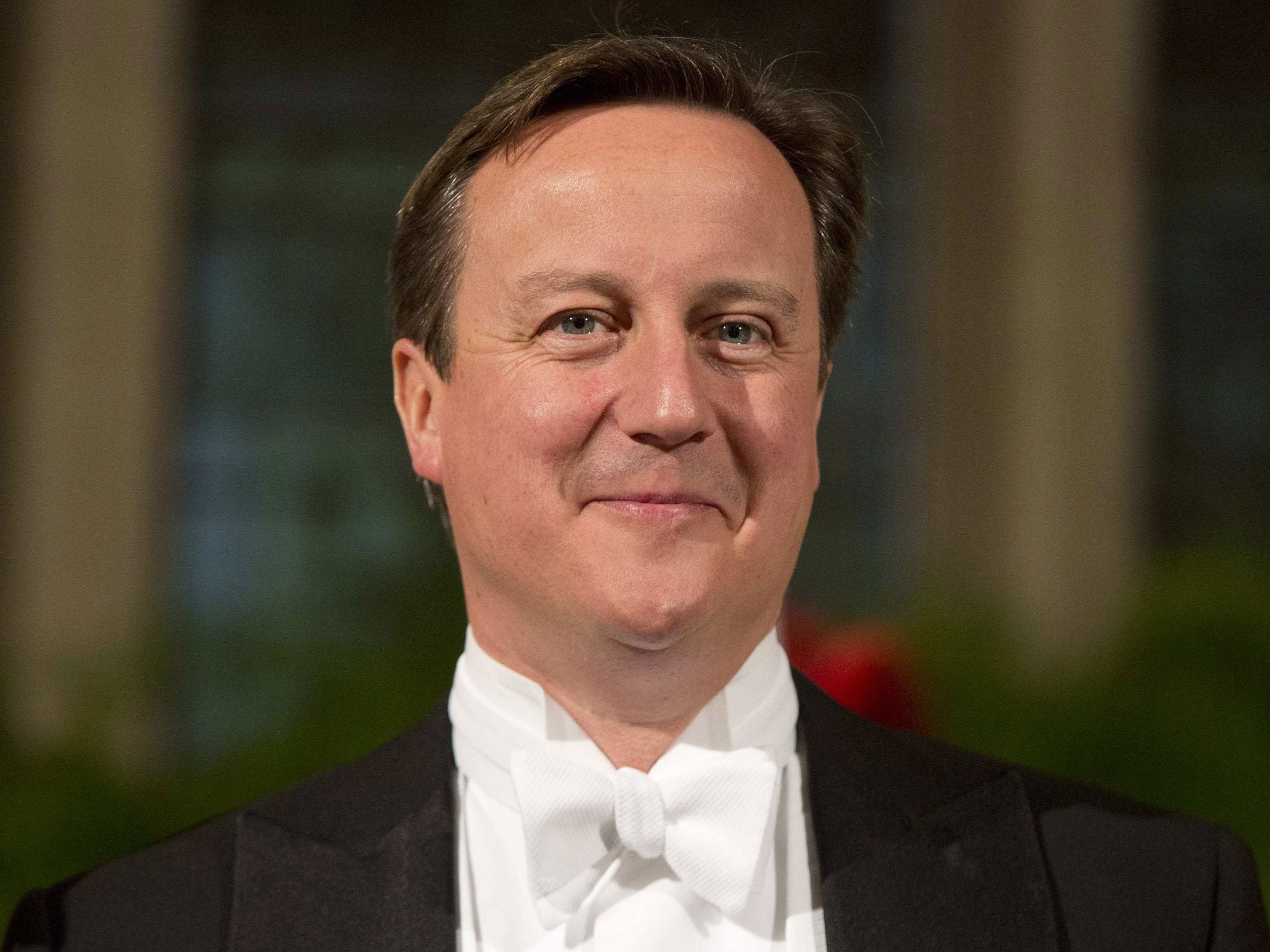

The secret life of David Cameron

In choosing ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ as his favourite film, David Cameron is disclosing a fantasy of self-sacrifice as much as one of heroism

In reality, he is a brow-beaten desk jockey toiling for a cash-strapped, middle-ranking outfit loaded with crippling debt and desperate for new business. In his imagination, however, he thunders over the trackless desert to perform heroic feats of arms, a scholar-soldier of genius and a titan of freelance diplomacy who commands the loyalty, indeed the reverence, of grizzled sheikhs and cunning emirs. Earlier this week, in the wake of the peerless Peter O’Toole’s final curtain, we learned that Lawrence of Arabia is the favourite film of David Cameron. Who knows how much advance spin goes into every casual tweet from Downing Street? In any case, we can look forward to the Prime Minister’s next outing as a Twitter-happy film buff. That ought to tell us what he thinks about the Ben Stiller remake of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which opens here on Boxing Day.

For all his eccentricities, T E Lawrence did manage what Cameron has this year failed to do. He rode into Damascus on 1 October 1918, at the climax of the British-sponsored Arab revolt. That led to the creation of a short-lived and ill-fated pan-Arab state under the Hashemite emir Faisal. To many cooler heads, the Lawrence of Arabia cult has derailed UK policy in the Middle East for almost a century. It has tempted the British into the sort of adventurism that rests not on strategic common sense, still less on any concern for the well-being of the region’s peoples, but on reckless fantasies of maverick brilliance. Lawrence did not, in fact, ride non-stop on his camel across the Sinai peninsula in 49 hours after his legion’s victory at the battle of Aqaba in 1917. (It took him three days, and he did sleep.) Still, it has suited myth-making politicians and publicists ever since to peddle this and other legends. Thus far, the prime ministerial camel lacks a saddle. In late August, Parliament narrowly blocked the Government’s push to authorise military action against the Assad regime. But does the PM’s “spontaneous” tweet – which, by the way, seems to revise his previous passion for The Guns of Navarone – hint that a Lawrentian gallop still tempts him?

Neurotic, erudite, masochistic, self-hating, and prey to sexual complexities that continue to baffle his biographers, Lawrence makes an odd choice of hero for a modern machine-politician who must project a PR-polished, family-friendly version of “normality”. But then British heroes of that vintage did tend to be curious characters. Above all, they display a distinct capacity to make things difficult for themselves. From Robert Falcon Scott of the Antarctic, vehement in his attachment to “man-hauled” sleds rather than labour-saving – and life-saving – dogs and skis, to George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, scaling Everest with minimal oxygen supplies and dressed in woollens that Bernard Shaw thought might serve for a “Connemara picnic”, the awesome deeds of courage and endurance that have passed into national mythology often seem to go hand in hand with a high level of wilful self-punishment. If Lawrence himself was indeed a masochist in the erotic sense, then he seems to have enjoyed a good deal more self-knowledge than other hardship addicts of his age.

This is the season when killjoy pundits like to flay us for the sins of sedentary self-indulgence. Humbug. At Christmas, raise a glass (or two) to sociable pleasure. Lawrence-style orgies of self-denial and self-flagellation may inflict much more lasting harm. The ascetic may tempt us into worse risks than the voluptuary. Look at the career of Lawrence or his Edwardian peers as they hack through jungles, trudge towards poles or climb the loftiest peaks, and their hunger for suffering feels very much a boy thing. The life of Lawrence in particular, however, shows many of the traits – including a self-critical perfectionism directed against his own body – that you will also find in young, female anorexics.

If sex sells, then so too does sacrifice. Next year, the world will commemorate the outbreak of a war that millions in the Europe of 1914 welcomed as a sacred opportunity to lay down their lives for their country. Rupert Brooke’s gung-ho sonnet “Peace” spoke for the youth of a bellicose continent when he rejoiced in the rush towards purifying war “as swimmers into cleanness leaping”. Soon enough, that “cleanness” would reveal itself as a miasma of mud, blood, torn flesh and shattered bone. But the lure of ennobling pain – from extreme physical endurance all the way to battlefield “martyrdom” – persists. Also this week came news that Ifthekar Jaman, a former Sky employee from Portsmouth who had travelled to Syria as a warrior for an al-Qa’ida-affiliated group, had found the death in “holy” combat that he appeared to seek. According to reports, his comrades, hearing his name on the list of the dead, “literally screamed with joy”. Yes, joy. In Britain, the self-sacrificial urge of Rupert Brooke undoubtedly endures – but among wannabe jihadis.

Half a century ago, at the dawn of the rationally hedonistic 1960s, it might have looked as if the ideal of sacrifice had shot its bolt. In the memorable – and, at the time, controversial – “Aftermyth of War” sketch from the Beyond the Fringe revue, Peter Cook’s RAF officer tells Jonathan Miller: “I want you to lay down your life, Perkins. We need a futile gesture at this stage. It will raise the whole tone of the war. Get up in a crate, Perkins, pop over to Bremen, take a shufti, don’t come back.” Today, even for people who imagine that they share not a single strand of cultural DNA with would-be shahids (“witnesses” to faith, or martyrs), futile – or not so futile – gestures that call for a measure of risk and pain still secure respect. Prince Harry was once better known for escapades in the kind of club where you might encounter a different variety of “snow” and “ice”. Yet he has just accompanied injured servicemen and women to the South Pole on the “Walking with the Wounded” expedition. Suffering in common, however symbolic, still becomes a prince.

But let’s return to Walter Mitty, whose fantasy life Hollywood has distorted once again. (Danny Kaye starred in the first travesty, in 1947.) Those who have never read James Thurber’s New Yorker story from 1939 (or, like me, who had pretty much forgotten it) might imagine that Mitty the suburban drudge dreams of luxury, comfort, pleasure and celebrity. Far from it. In keeping with the spirit of his age, the secret life turns on episodes of dire peril and terrifying ordeals of pain, danger and stress. Mitty pilots a “huge, hurtling eight-engined Navy hydroplane” through a hurricane. He saves a “close personal friend of Roosevelt” on the operating table thanks to inspired last-gasp surgical improvisation. As a Great War air ace, he flies alone against “Von Richtman’s circus”, humming “Auprès de ma Blonde” after downing a stiff brandy. In the end, he faces a firing squad “erect and motionless, proud and disdainful”. Mitty’s hidden desires lead him not towards indulgence but to – death.

In 1920, in the aftermath both of the Great War and his daughter Sophie’s death in the Spanish flu pandemic that swept across Europe, Sigmund Freud published his most unsettling work. Beyond the Pleasure Principle revises his core belief that libido, or life force, alone fuels human existence. Instead, it posits a countervailing “death instinct”. To Freud, in this mournful mood, “the aim of life is death”. In a psychological syndrome such as Lawrence-style masochism he detects “a self-injuring tendency which would be an indication of the death instinct”. Freud’s drive towards destruction, the Thanatos that rivals Eros, has never met with universal acceptance. However much of a hangover, moral or physical, the pursuit of pleasure may bring, it feels reassuringly human. The notion of a drive towards self-harm disturbs us far more.

Yet, in the form of self-denial, if not outright self-annihilation, hardship still attracts. After Christmas, plenty of guilty guzzlers will embark on doomed diets – futile gestures, indeed – in an annual outbreak of the “primary masochism” that Freud diagnosed in the human animal. If he was right, then politicians enraptured by the self-imposed ordeals of a Lawrence or a Scott may reckon that appeals for sacrifice may strike a deeper chord than promises of bliss. Very occasionally, they may be justified. And they may work.

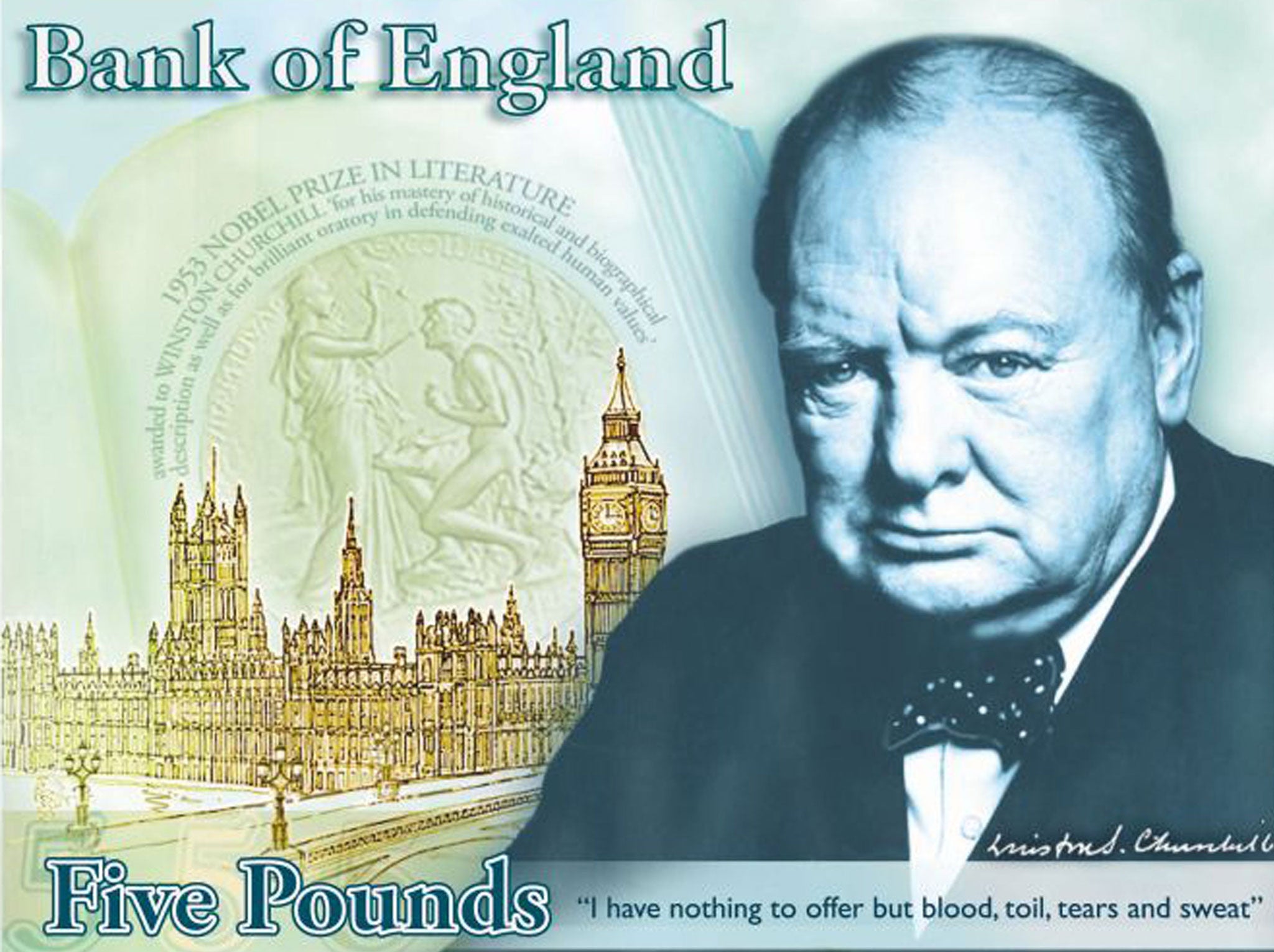

A couple of days ago, the Bank of England revealed its draft design for the plastic (sorry, “polymer”) £5 note that after 2016 will carry the image of Sir Winston Churchill. There, along the bottom, ran these words from his first speech as Prime Minister: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.” Of course, Churchill said many other things as well. About Lawrence, with whom he collaborated to carve up the Middle East at the Cairo Conference of 1921, he commented that “the world looks with some awe upon a man who appears … indifferent to home, money, comfort, rank, or even power and fame”.

Churchill himself had none of that desert-dry asceticism. Even in the darkest hours of war, the world’s most famous consumer (in industrial quantities) of Pol Roger champagne never let his supplies dwindle. “In defeat I need it. In victory I deserve it,” he insisted. Lawrence’s whip or Winston’s glass? Over the coming days, most of us will vote with our appetites. And the majority will, rightly, resist the temptation of abstinence.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies