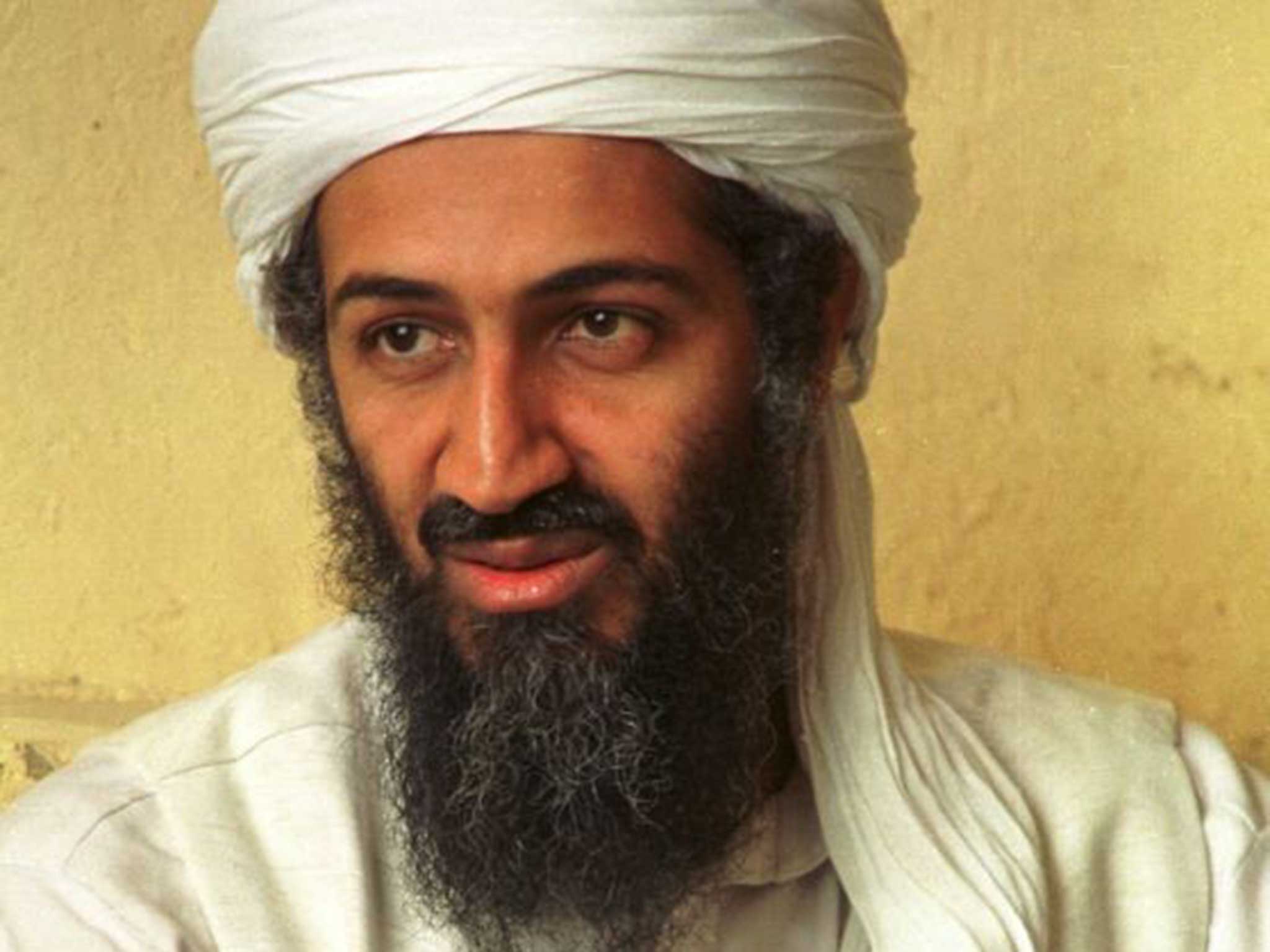

So, it turns out Osama bin Laden was a terrorist monster with a tender side...

After all, evil is a man-made construct designed to help our tiny minds grapple with unthinkable things

Osama bin Laden: loving family man, good with kids? Yes indeed, as some of the letters just released by the US demonstrate. There’s plenty of stuff about jihad, about “killing and fighting the American people and their representatives”. But there’s also simple human concern for his several wives, 20 children and numerous relatives.

“By God, I miss you so much,” he writes to his daughter, Umm Muadh. He asks how her son is getting on at school. “What is his latest funny news?” In another letter he asks one of his wives to look after his daughters, “and be careful of bad company for them”.

His son, Saad, was being groomed as his successor when he was killed in a drone strike in 2009. But Bin Laden, too, had a soppy side. “Know that you do fill my heart with love, beautiful memories, and your long-suffering of tense situations in order to appease me and be kind to me,” he wrote to his wife. “You are the apple of my eye, and the most precious thing that I have in this world.” This is all irrelevant, some might say. The fact is, Bin Laden senior was the brains behind the wickedest terrorist act in history. He was pure evil, and the only emotion we need to feel here is relief that he’s dead.

Similarly – though some way down the scale of iniquity, perhaps – my first thought when I heard about the recent deadly biker shootout in Waco, Texas, was along the lines of the late, great comedian Bill Hicks, who talked about someone taking LSD and throwing themselves off a roof thinking they could fly: “Good. The world just lost another idiot.” Nine of them, in fact, in this case, nine dead idiot bikers.

But then the pictures started to come in. There’s Matthew Mark Smith of the Cossacks Motorcycle Club: he’s hugging his girlfriend Kelsey Anne; lying in bed asleep; smiling at the camera with a baby in his arms. He looks like a nice, sensitive bloke; he worked for an electronics company called Geek Squad.

There’s his Cossack comrade Wayne Campbell, flanked by a couple of young women, looking like an off-duty lecturer; there he is wearing a suit, with his girlfriend Charla in an attractive black dress. They look as if they’re off out to a nice restaurant for the evening. Even on his bike he looks like Mr Respectable having his regulation midlife crisis, not a homicidal outlaw on two wheels. There are lots of photos of Rick Kirschner, the Cossacks’ Sergeant at Arms. In one of them, he’s in his flat with his wife Ashley – he’s in shirt and tie, she’s in a lovely blue dress. They look so affectionate, so decent, so ordinary. Police, meanwhile, were yesterday still totting up the weaponry recovered from the Twin Peaks restaurant: they were up to 118 handguns, 157 knives and an AK-47.

We all, clearly, have sometimes wildly contrasting sides to us. And that goes for just about everyone, even biker gang members, even wagers of jihad. Even Nazi mass-murderers. In the recent BBC4 film Himmler: the Decent One, Heinrich Himmler’s letters revealed him to be a doting husband and dad.

“I am so sorry that I forgot our wedding anniversary for the first time but I was so busy these past few days,” he writes to his wife Margarete. In 1943, he ordered the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, then wrote home: “My dear mummy. A few quick lines. Enclosed are two packages and a piece of fruit cake.” I’d find it difficult to argue against anyone who found this juxtaposition utterly obscene. But even so, it’s a clear demonstration that even Heinrich Himmler had his good points.

As I type these words I can feel a Twitterstorm on the horizon but, were they still around, Rebecca West and Gitta Sereny would know what I mean. For her book The Meaning of Treason, West attended the trials of William Joyce, Lord Haw-Haw. She saw in the dock ‘a lively, wisecracking, practical-joking little creature... That he was a civilised man, however aberrant, was somehow clear before our eyes.”

Sereny dedicated her life to getting inside the heads of supposedly “evil” people. In fact, she didn’t believe in “evil” at all; I believe it’s a man-made mental construct designed to help our tiny minds grapple with unthinkable things.

Sereny famously befriended Albert Speer, eventually getting him to confess – to himself, as much as her – that he knew all about the Final Solution. She ended up liking him, and insisted she’d detected a capacity for moral redemption. Even in her dealings with Franz Stangl, who was held responsible for the murder of 900,000 people, she saw some good, and decided that he was “not an obviously evil man”.

While “evil” may not exist as a single, over-arching concept, I think it is possible to describe individual acts as evil, in our attempts to grasp what makes people do abominably bad things. But unless we realise that however badly a person behaves, in other respects they’re just like us, we’ll never be able to properly understand why they do what they do.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies