The real villains of the Abu Qatada case are not Theresa May, Jordan, or European courts - but MI5

Those who wrongly blame Strasbourg have the wind in their sales. But if this preacher of hate is deemed a threat to British security, why was he not tried in a British court?

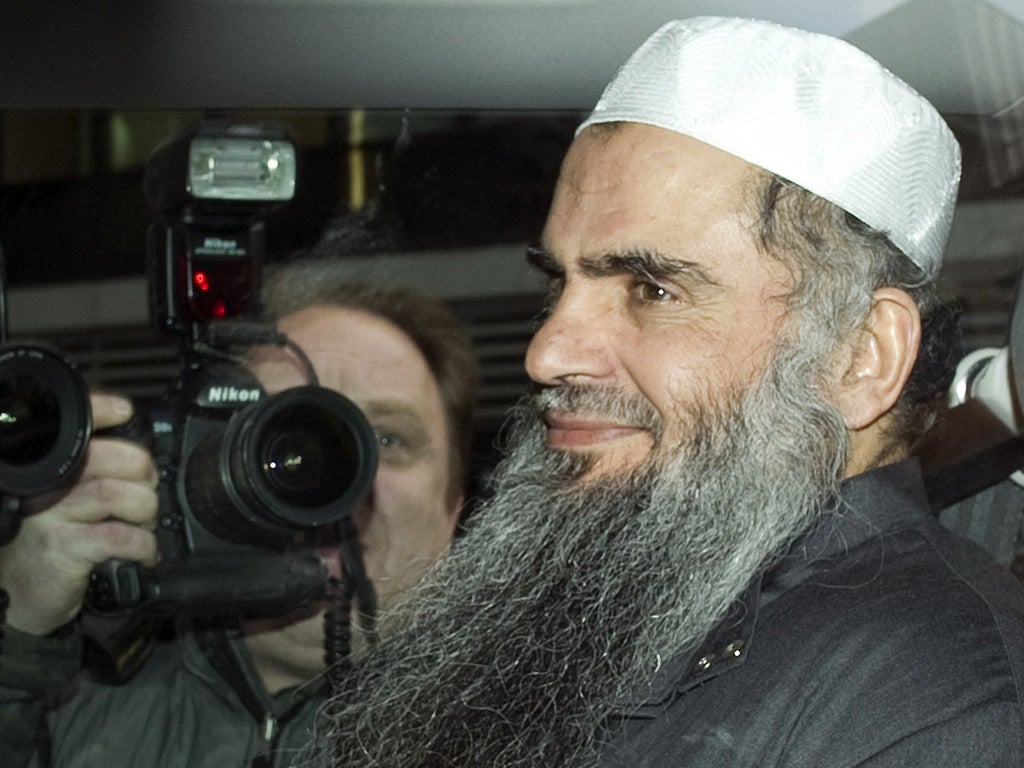

Any successful politician has to be attuned to the public mood. And in wanting two fearsome Muslim preachers out of the country, David Cameron has been spot on. The Prime Minister did not conceal his delight when the hook-handed cleric Abu Hamza was finally on a flight to the United States. And this week he vented his frustration that Abu Qatada had won his release. Cameron said he was “completely fed up that this man was still at large in our country”.

Whether his fury was entirely justified is another matter. In these and similar cases, ministers have been adept at throwing up their hands and acting powerless. On the positive side, they cite the independence of the UK judiciary, separation of powers and all that laudable constitutional stuff. Alternatively, they come over all xenophobic and the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg bears their wrath.

Recrimination

The ECHR has the merit, for its detractors, of sounding as though it is part of the EU behemoth, even though it is not. This makes it easy for ministers to present its rulings as eating away at national sovereignty, especially when they ignore the proportion of cases the UK wins.

The Home Secretary is now said to be closeted with lawyers, scrabbling for grounds on which to appeal. She may also be trying to extract new guarantees from Jordan to the effect that, if Abu Qatada is extradited to stand trial on terrorist charges, he will not face evidence obtained by torture. Theresa May appeared to have secured such guarantees in Jordan last March, but they were not enough for the Special Immigration Appeals Commission. There might be a chance, but perhaps not a good one, that the Government will eventually get its way.

Until the desired result is achieved, however – if ever it is – the air will be thick with recriminations about the delays, the cost, and the apparent imbalances in a system that allows inconvenient characters to stay in Britain long after they have overstayed their welcome. With Abu Qatada, the Government seems to have undermined its own case by sounding out Jordan about a pardon.

This would, of course, have allowed the authorities to extradite Abu Hamza with a clear conscience. But any talk of a pardon – now clarified as applying only to offences for which he was tried in absentia – was unlikely to be welcome to the Jordanians. This was probably not the best course for the Home Office to have pursued.

Stalemate

So there is stalemate. The Government has been made to look impotent, and those who blame Strasbourg, or – mistakenly – the EU, have the wind in their sails. But this is a scenario which, in a way, suits ministers because it neatly deflects attention from the obvious option that this government, like its predecessors, has rejected.

The truth is that, if the authorities regarded Abu Qatada as a serious threat to the UK – as they appear to do – he could and should have been tried in a British court. In effect, we are trying to outsource our justice to Jordan – and in Abu Hamza’s case, to the US.

If this were happening because the UK authorities saw no grounds for trying these individuals here, they could say just that, drop the charade of pre-emptive control orders, and let Abu Qatada and company live their lives or face extradition to countries where they are wanted. They would cease to be a British political issue.

The Government, though, wants it both ways. It regards these preachers as dangerous. “We believe,” said Cameron, of Abu Qatada, “that he’s a threat to our country.” Which strongly implies there is evidence. But the Government cannot bring itself to produce that evidence in court because the security services, so it is said, insist it would jeopardise national security.

Their specific objections appear to be twofold: requiring intelligence officers to testify in court could imperil their safety, while admitting evidence from telephone surveillance could assist the enemy by giving away covert techniques. Not everyone agrees, though. In 2008, Prime Minister Gordon Brown said he approved the use of intercept evidence, but four years later it is still not permitted.

The Justice and Security Bill, which returns to the Lords next week, is seen by many in government as part of a solution. And it has been stoutly defended as such by Baroness Manningham-Buller, a former head of MI5, who said that it would allow the Government to contest, in particular, certain compensation claims against the security services that it was currently obliged to settle.

But it is not clear how much of a remedy this legislation will be, if any. It permits any case with a security aspect – or any case, perhaps we should say, that can be presented as having a security aspect – to be heard at least partly in camera. Is this not likely to perpetuate a culture of secrecy that itself will foster a continued sense of impunity?

It is beyond time that the Government – and the criticism applies not just to this government – stopped sitting on the fence and finally made its choice. The question is this: which represents the greater threat to the UK’s security: the use of intercept evidence in court, or leaving Abu Qatada – and others – at large? I do not know the answer.

Disingenuous

But the security services seem to have convinced successive governments that their officers and methods take precedence. And if that is so, it is worth asking why we, as taxpayers, employ and fund them if, when their evidence is most needed, their right to secrecy has the effect of thwarting justice?

We have no way of knowing how far, even whether, the security services or individual officers may have abused their position in relation to “rendition” and torture during the years after 9/11. It must be doubtful whether any of these cases will ever see the light of day. But when ministers complain about the foibles of – our own – liberal judges or the excesses of Strasbourg, they are being disingenuous.

If the Government really wants to end a situation where it appears hostage to outside forces, it has the solution to hand. It must pluck up courage and level with the security services, who still hanker after the hush-hush world of their past.

Lady Justice Hallett showed what could be done, even under current law, when she won the right to question intelligence agents at the 7/7 inquest, against the ferocious resistance of MI5 and MI6. The post 9/11 panic “war on terror” gave security services on both sides of the Atlantic an inch, while allowing them to take a mile. That leeway must be taken back and the Government’s authority restored.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments