In Viennese painting of the early 20th Century, you get a sense of horrors to come

Freud saw culture as a veneer through which destructive forces could break

Can art sometimes sense what is coming? The National Gallery provides an interesting test with its exhibition, Facing the Modern – The Portrait in Vienna 1900. Do these pictures provide intimations of the cataclysm that would soon arrive, a genocidal civil war in Europe? For the whole thing began in Vienna, which was then the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Starting with the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the conflict would continue with interludes right through the Second World War until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

On 28 June 1914 the heir to the throne of Austro-Hungary and his wife were assassinated in the provincial town of Sarajevo. That was the clap of thunder in the summer sky. The assassins were three 19-year-old Serb youths. Three weeks later the Austro-Hungarian government addressed an ultimatum to Serbia that Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, called “the most formidable document I have ever seen addressed by one state to another that was independent”. From then onwards war was inevitable. The crisis escalated so that on 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany, Austro-Hungary’s chief ally.

But Vienna was an unlikely war-maker. The arts dominated the city. Hardly anywhere else in Europe was so passionately committed to culture. Mahler was the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic and composed four symphonies between 1901 and 1906. In the same city, Schönberg was to music what Picasso was to painting. Freud, whose address, Berggasse 19, Vienna IX, was to become famous all over the world, was growing in influence.

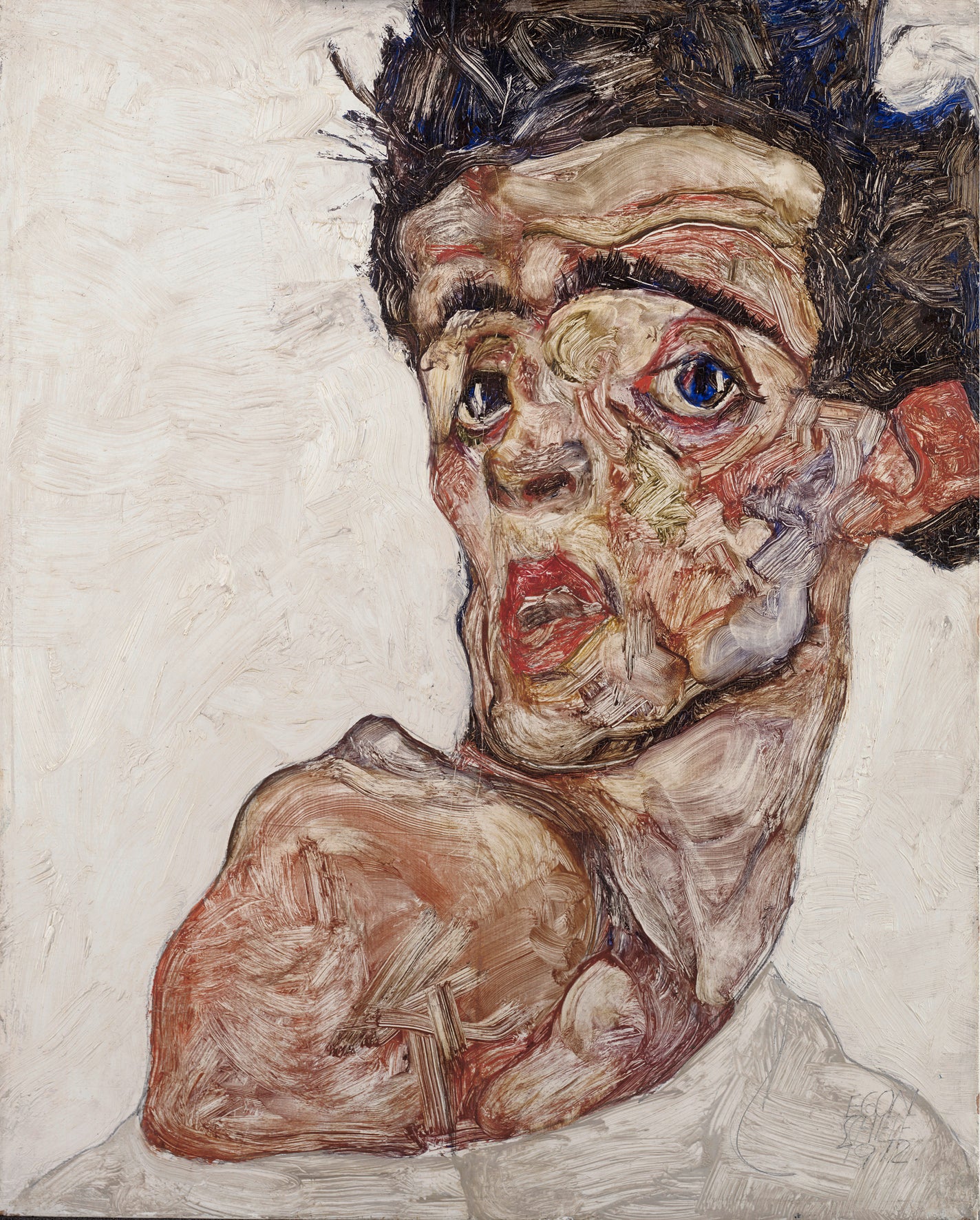

There was also Ludwig Wittgenstein, the son of a steel magnate and patron of the arts, who was beginning to develop his challenge to traditional philosophical thinking. Viennese painters, too, were in the first league of European art – among them, Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), Oscar Kokoschka (1886-1980) and Egon Schiele (1890-1918), all well represented in the National Gallery show. As Stefan Zweig noted: “Here the battle raged: about the unconscious, about dreams, about new music, the new way of seeing, the new architecture, the new logic, the new morality.”

So Vienna wasn’t a belligerent place. The writer Robert Musil observed that “ruinous sums of money were spent on the army, but only just enough to secure its position as the second weakest among the great powers.” He also noted that “there was some show of luxury, but by no means in such over-refined ways as the French. People went in for sports, but not as fanatically as the English. The capital, too, was somewhat smaller than all the other biggest cities of the world, but considerably bigger than a mere city.”

In any case, Vienna was to be the victim rather than the victor. It lost its empire in 1918 and languished into being the capital of a rather small German speaking country. But not so minor that it could avoid being annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938.

Zweig, born in Vienna in 1881, who went through all the horrors and died in exile in Brazil in 1942, is the best guide to the period. In his autobiography he wrote of his “unique generation, carrying a heavier burden of fate than almost any other in the course of history”. He said that as an Austrian, a Jew, a writer, a humanist and a pacifist he had always stood “where those volcanic eruptions suffered by our native continent of Europe were at their most violent”. He added: “We have found that we have to agree with Freud, who saw our culture and civilisation as a thin veneer through which the destructive forces of the underworld could break through at any moment.”

Did Vienna’s artists working just before the outbreak of war, sense these destructive forces? Certainly Vienna was more likely to do so than London, Paris and Berlin. It was much more cosmopolitan, the capital of an empire straddled across the middle of Europe rather than one with possessions spread across Africa and Asia. It was a sort of central European union with a common currency.

It contained 11 official nationalities – Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Romanians, Ruthenians, Poles and Italians. They all demanded more independence, but hardly anyone wanted full separation. As economic growth accelerated in the second half of the 19th century, Vienna grew swiftly. Its middle classes comprised many families with Jewish immigrant backgrounds and connections. Anti-Semitism made its appearance with the election of Karl Lueger as Mayor in 1898.

On show at the National Gallery is Viennese society from the early part of the 19th century to the outbreak of war, plus a few remarkable items from 1918 and 1919. The sitters are, for the most part, well-to-do bourgeoisie and minor nobility. Cäcilie Freiin von Eskeles, painted in 1832 – what the catalogue calls a “salon lady”, married to a banker, a correspondent of Goethe – breathes self-assurance.

Then there is the pretty Hannah Klinkosch, daughter of a Jewish manufacturer of silverware, posing seductively in 1875, who converted to Catholicism before she married an economist and then, after that was annulled, shot to the top of society by marrying the Prince of Liechtenstein. Of this group of pictures, however, the one that brought me the greatest pleasure is Klimt’s Portrait of a Lady in Black (1894). She stands with one hand resting on a chair, wearing a sophisticated black dress, erect, admittedly plain yet striking. She was born in modest circumstances and married a master baker. It doesn’t sound much, but Klimt gives her a straight-backed elegance.

While there is no sign of trouble ahead in these pictures, by the early years of the 20th century, Kokoschka and Schiele were doing work suffused with anguish. One contemporary observer described Kokoschka’s 1909 picture of the avant-garde poet, Peter Altenberg, as “half coffee- house Jesus, half cab driver of eternity”. Altenberg’s bloody hands, drooping moustache and staring eyes make him a desperate figure. He appears to be saying – rescue me!

Kokoschka’s portrait of the distinguished art historian, Hans Tietze and his wife, Erica, done in the same year, shows Hans talking but Erica not listening. Hans also has what looks like blood on his hands. This same theme of alienation is given its fullest expression two years later in Anton Kolig’s painting of the Schaukal Family. Father is reading, mother is lost in thought and the three children are each self-absorbed. There is no communication.

Schiele presents himself as a tortured soul – see his Self Portrait with Raised Bare Shoulder of 1912. He is expecting nothing good to happen. But he provides the most memorable picture in the show. This is his The Family (Self Portrait) painted in 1918 and thus after the storm has begun to rage. Nude and defenceless, the family – father, mother and baby – appears watchful, united for what might come their way. But it was not to be a happy ending. The parents succumbed to Spanish influenza a few months later. Schiele’s last artistic work was Portrait of Edith, dying. She expired on 28 October 1918; he passed away three days later. These two artists, Kokoschka and Schiele, had truly shown in their painting the scale of the disasters to come.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies