Who cares if Americans can enter the Man Booker Prize?

... we should. If this country's 'provincial' writers are overshadowed now, they will get barely a passing glimpse in the bright, transatlantic literary future

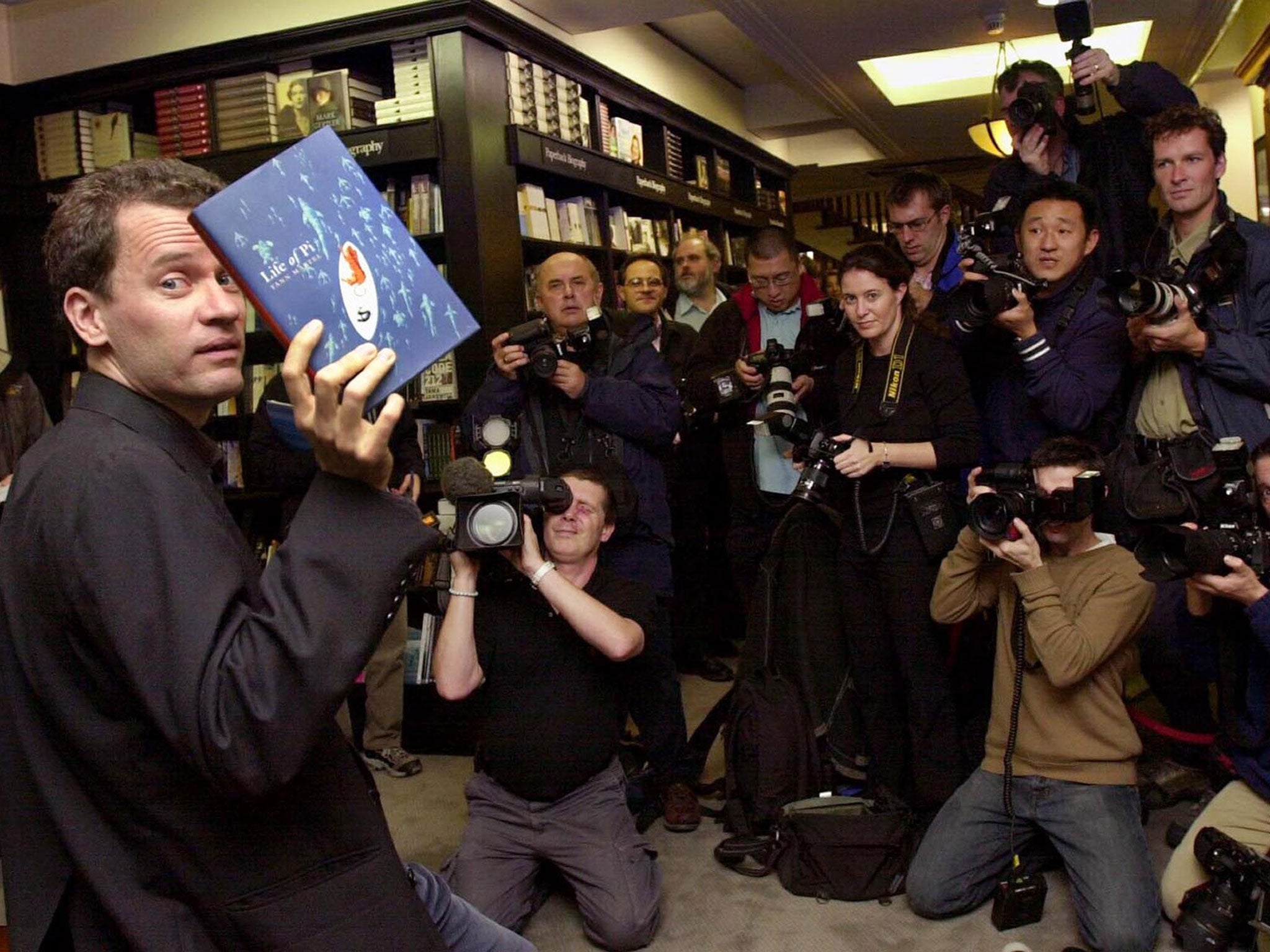

Of all last week's scraps of arts world intelligence, the news that the Man Booker Prize was extending its catchment area to include any novel published in English in this country, thereby admitting a whole crowd of distinguished Americans to the party, was by far the most predictable. Like business, literature is either global or niche these days, and a prize which hitherto confined itself to the Commonwealth, Zimbabwe and the Republic of Ireland had begun to look increasingly out on a limb.

Equally predictable was the response of much of that dispersed and variegated demographic known as the UK literary community. This (primarily) westward-gazing rule-change is, it hastened to insist, unnecessary, for there are already international and Asian Man Booker prizes. It will increase the weight of the institutionalising blanket that already hangs over British literature like a shroud.

The new rules are, additionally, weighted in favour of major publishers at the expense of maverick, minor outfits, and the general effect will be to increase the chances of the creative-writing graduate published on both sides of the Atlantic, who spends his, or her life, commuting between teaching jobs at Iowa State and Bologna, while diminishing the hopes of Anne Unknown of Sheffield, author of "I Were Reet Mardy T'other Night".

This is an exaggeration, perhaps, but not much of one. As my colleague Natalie Haynes, a judge of this year's prize and shortly to publish a debut novel herself, nervously summed up in The Independent: "While my inner reader cheers at the prospect of more good books in the mix, my inner writer is worried that I now need my small publisher to prefer my book to everything else they're publishing next year if it's even to be considered." At the same time, the welcoming into the fold of America's and perhaps Brazil and Israel's finest has a symbolic value far beyond its immediate consequences, for it marks a further stage in a process that has been going on for well over a century: the marginalisation of a distinctive and distinctively "English" literary culture.

To proclaim the virtues, or lament the exclusion, of "Englishness", in cultural or any other terms, is a chancy business at the best of times, fraught with suspicions of chauvinism and special pleading. But it is a fact that, since at least the 1920s, nearly every intellectual who decides to pontificate on the subject of native literary culture does so on the assumption that it is inferior to overseas versions. The very first essay in T S Eliot's The Sacred Wood (1920), for example, a profound influence on the literary criticism of the mid-20th century, deplores the absence of a home-grown critic who can demonstrate that George Eliot is a more "serious" writer than Charles Dickens, and then go on to prove that Stendhal is more serious than either of them.

Leaving aside the pool of clear water that is supposed to separate Middlemarch and Dombey and Son, why should Eliot maintain that the author of Scarlet and Black was a more serious writer than his English equivalents? What, in this context, does the word "serious" actually mean? In fact, Eliot never says; he merely takes it as a given, in much the same way as the aesthetes of the generation presumed that the really smart money was on Verlaine and Rimbaud.

Come the 1950s, the Gallophilia of upper-brow literary culture had reached such a pitch that it was a source of popular humour. The sections in Lifemanship, one in the series of Stephen Potter's "gamesmanship" books, canvass the "absolute OK-ness" of France for anyone bent on advertising their sophistication, while Kingsley Amis's Lucky Jim is rife with insults aimed both at French titans and their English sponsors. Thus, Professor Welch and his pretentious son Bertrand are said to resemble "Gide and Lytton Strachey, represented in waxwork form by a prentice hand".

The habit of certain well-placed cultural opinion formers to assume that, of all the bright literary flora shoved under your nose, the least interesting are the blooms that flourish in your own back yard had several important consequences. In the 1950s, it led to the blanket categorisation of new British writing: the labelling, to take only the most flagrant example, of anyone hailing from north of the Trent who hadn't obviously attended a public school as "a northern working-class writer", whatever the idiosyncrasy of the work he produced. In the 1960s and 1970s, it led to the championing of vast numbers of American novelists whom posterity hasn't tended to treat with any great respect and the belittling of home-grown talent on the grounds of the latter's "provincialism".

In the 1980s, as a new cosmopolitan wave swept over the Waterstone's shelf, led by Salman Rushdie's Booker-winning Midnight's Children (1981), it led to a debilitating fashion for magic realism, butterflies swarming above South American jungles and a set of stylistic conventions quite as tedious as those of the quaint English realism they were supposed to be replacing.

This is not a complaint about Midnight's Children, which deserved every prize going. It is not a complaint about – to name a few celebrated Americans now eligible for the Man Booker – Paul Auster, Annie Proulx and Richard Russo, although it might be pointed out that at least half of the fascination with which we greet US writers stems from their exoticism, and that book groups in Nowhere, Nebraska probably feel the same way about Anita Brookner. It is merely to suggest that there is a fine old tradition of "provincial", non-metropolitan writing in this country which, if overlooked now, is going to get even less of a look-in in the bright, transatlantic literary future.

It is the tradition which brought us the Birmingham-based Tindal Street Press (now, inevitably, subsumed into a London publisher), the Northumberland-based Flambard (now, naturally, defunct after the removal of its Arts Council grant) and the Norfolk-based Salt; and it is one which, given the number of genuinely fine writers it has produced, we neglect at our peril.

As for some of the factors calculated to increase this neglect, well the new Man Booker rules are right up there at the top of the pile. I had a phone call not long ago from an old friend of mine, the novelist John Murray. Murray is, among other distinctions, the author of Radio Activity (1993) a swingeing satire on the Cumbrian nuclear industry, much of it written in local dialect, and one of the funniest books I have ever read. Previously sponsored by Flambard (see above), he is currently without a publisher, and a job, and has gone off to Greece to start a writing school. What will the newly reconstituted Man Booker do for Mr Murray? At a guess, absolutely nothing. On the other hand, it should make a nice little bonus for one or two of those creative writing tutors currently plying their trade in the universities of the American Midwest.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies