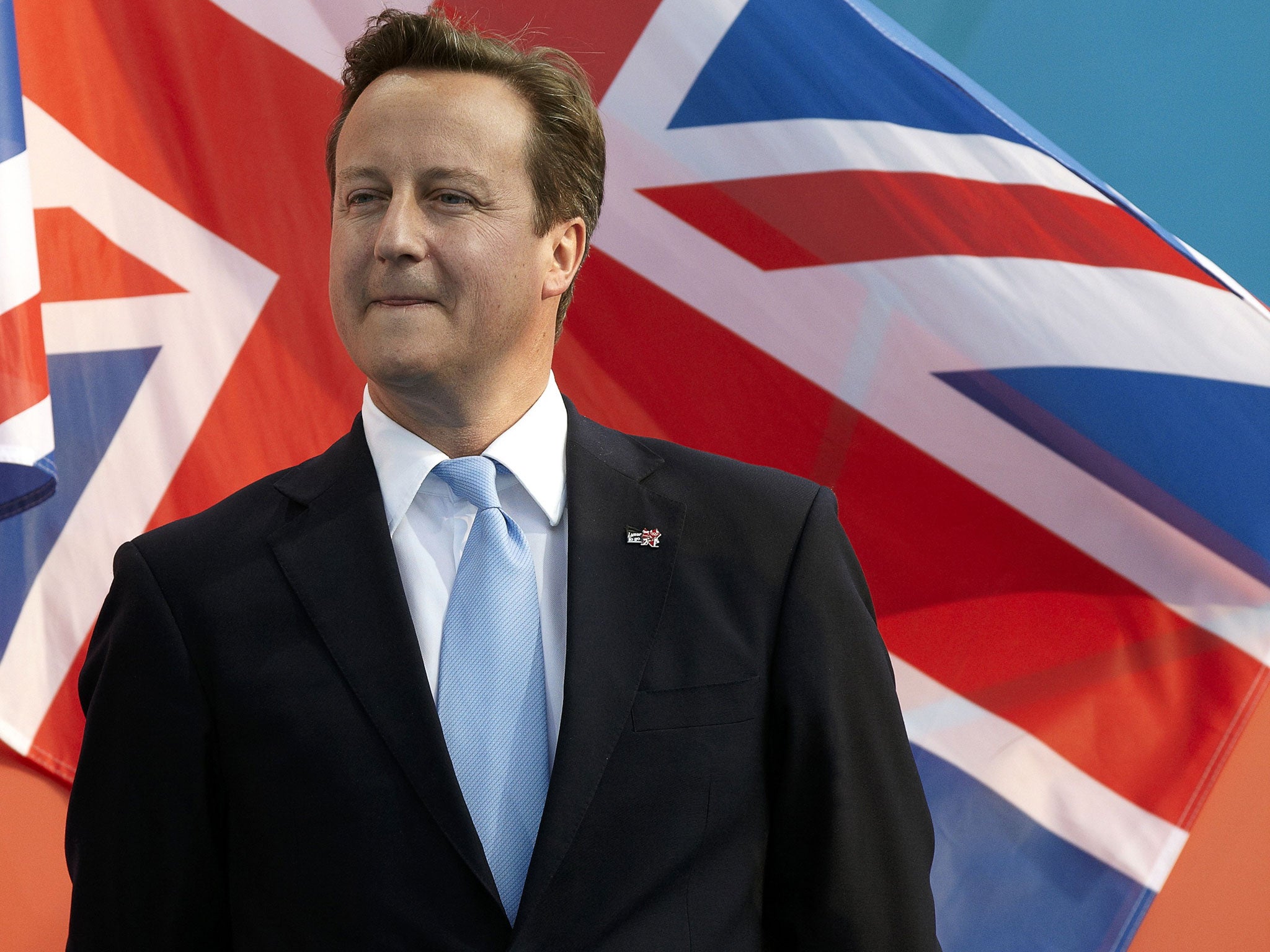

Will practice make perfect for the PM?

Cameron deserves - and won't get - modest credit for his limited intervention in Libya

What has David Cameron in common with orchestral musicians, chess players and a golfer? They have all been used to test the "10,000 hours" rule. This was formulated by Anders Ericsson, professor of psychology at Florida State University, in 1996. He found that the most important factor for musicians in Berlin achieving the highest level of performance was to complete 10,000 hours of "deliberate practice". Other studies found that it also applied to chess and some sports. Dan McLaughlin of Portland, Oregon, is now testing the rule by trying to become a professional golfer, with 10,000 hours of deliberate practice. He has another 6,259 to go.

Cameron, on the other hand, has recently completed his 10,000 hours of practice at being Prime Minister. Assuming he does 12 hours a day before settling down to what he calls "a bit of back to back", watching consecutive episodes of The Killing, two-and-a-half years is the mark. According to Ericsson's theory, he should now be an expert at the job.

His predecessors lend some support to the theory. Gordon Brown was just getting the hang of the job by the time of the 2010 election. And Tony Blair seemed to gain confidence at the start of 2000, when he "stole" Brown's "effing Budget" by announcing a big increase in NHS spending.

So, how is Cameron doing? Last week was something of an assessment. He was given two tasks: to make a historic statement on the nation's long-term future; and to deal with a crisis. He made a bit of a mess of the first, although the examiners have not actually seen his paper yet, in which he is believed to have attempted one of the harder "extension" questions: "Show how the UK can simultaneously (a) threaten to leave the European Union to force others to agree to its demands and (b) insist that it is in the UK's national interest to stay."

But he did well on the second, responding to the hostage-taking in Algeria. These unexpected shocks are important moments for political leaders. I thought Blair's "people's princess" weirdly hammy, and it looks in poor taste on YouTube now, but he spoke for the nation at the time. Recently, Barack Obama's response to the Sandy Hook shootings has lifted his approval ratings. And last week, Boris Johnson showed, with his tribute to the emergency services after the helicopter crash in London, that he could be dignified and prime ministerial as well as a P G Wodehouse buffoon.

We know that Cameron is a good judge of tone from his response to the Bloody Sunday inquiry. And we know that he has a quick and decisive mind; not that the Algerian crisis required him to decide very much, except to call off his Europe speech. What was interesting about Cameron's response to the raid on the desert oil field was the fluency with which he fitted it to an interventionist foreign policy. Sounding more Blairite than ever, he spoke in the Commons about "ungoverned spaces" providing bases for terrorism.

This is brave. British public opinion has been hostile to foreign military adventures since Iraq, and the idea of a "blowback" of terrorism targeting the British has been a powerful one since the London bombings of 7/7. And it is hard to resist the idea that the liberation of Libya, assisted by French, British and American forces, contributed both to the fighting in Mali and the Algerian raid by releasing weapons, soldiers and territory to what Cameron called "the most aggressive and violent form of militant Islam". Yet Cameron deserves – and won't get – modest credit for his limited intervention, authorised by the UN, in Libya, where the securing of a young democracy was recorded as a success story by Freedom House, the human rights group.

It could be argued that what he calls the "process" questions of his Europe speech do not matter much. They provide Ed Miliband with jokes that he tells us are "pretty good", and they greatly interest journalists, but the important thing is the policy. So, although Cameron gets poor marks for expectations management for telling someone months ago that he was going to give a big speech on Europe, the question is whether or not the promise of a referendum is a good idea. In the end, I think Miliband will suffer for appearing not to trust the people.

The fuss over the "virtual" speech – he has virtually given it now, with all the advance briefing – emphasises a recent change in politics, a speeding-up that has happened in just the past 18 months according to one Cameron adviser. In No 10, I am told, the acceleration of media commentary feels as though someone is pressing the fast-forward button on Sky+. BBC News 24, launched in 1997, was like pressing the button once – twice as fast. The internet was like pressing it again, at six times the speed. Then came blogs, times 12. And now Twitter provides instant commentary, at up to 24 times the speed once regarded as normal.

If Cameron has finally learnt how to do the job, he may find that the world has speeded up so much that he needs to start his training all over again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies