The decline and fall of the political biography

They are not what they used to be, partly because today’s MPs have less to write about

The bookseller remarked “That’s quite a size, isn’t it?”, as he inserted my copy of John Campbell’s Roy Jenkins: A Well-Rounded Life into its carrier bag. He was not exaggerating, for Mr Campbell’s opus – a successor to his equally monstrous lives of Margaret Thatcher and Edward Heath – weighs in at a gargantuan 816 pages. The notes alone are the length of a shortish novella and the list of acknowledgments extends to well over 100 names.

And yet, setting it down on the kitchen table, I was struck by a sensation that must once have stolen over a Dutch settler on 17th-century Mauritius back from a dodo hunt in which the prey seemed sparser than usual, the feeling that an end of an era was in prospect and that, to mix the metaphor, not much more fruit could be expected to fall from a tree whose roots seemed to be withering by the moment.

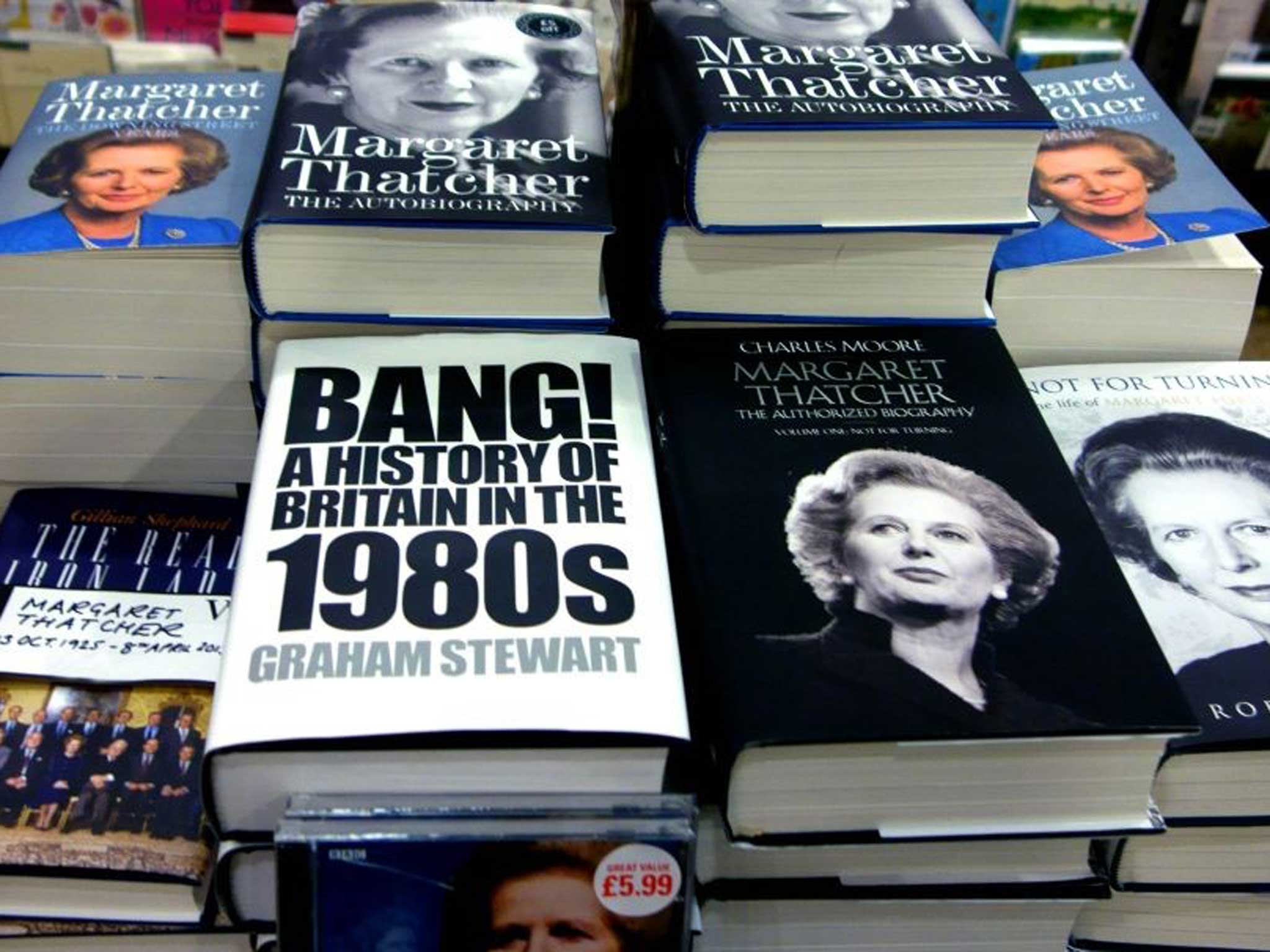

Call this a depraved taste if you will, but I have always been a fan of political biography. A quick head count along the shelves of the dining-room bookcase realised at least 70 items, ranging from the giants of the genre (Ben Pimlott on Harold Wilson, Susan Crosland’s account of her late husband, Tony) to wholly recherché offerings such as Peter Kellner and Christopher Hitchens’ instant life of James Callaghan, written to mark his accession to the premiership in 1976. Yet however diverse, this little library, sedulously accumulated over the course of three decades, is beginning to show its age. Most of the books date from the 1980s and 1990s, and 2013 produced only two additions to the catalogue – the first volume of Charles Moore’s biography of Mrs T and Alan Johnson’s memoir of his early life.

There are several reasons why the art of political biography is in sharp decline. One of them, naturally, is that publishers are less absorbed by a genre whose comparatively high outlay in terms of authors’ advances – I shudder to contemplate the number of desk-bound years Mr Campbell must have spent on Roy Jenkins – could, in the past, have been underwritten by newspaper serialisation deals. But another is that politicians, as a breed, are a much less enticing prospect when placed under the biographer’s lens, if only because of the comparatively short time most of them seem to spend in their chosen calling.

The old-style front-bench politician of the 19th and 20th centuries was usually a man, or very occasionally a woman, who devoted the majority of his adult life to politics. Gladstone, famously, spent nearly seven decades in the House of Commons, starting his career as a Conservative defending his family’s interests in the slave trade and ending it as the leader of a radical coalition in whose manoeuvrings one can detect the glimmerings of the welfare state. More recently, Harold Wilson served 38 years in the House of Commons, James Callaghan 42 and Tony Benn more than half a century.

The modern politician, on the other hand, tends to enter parliament at an absurdly young age and then leave it at a moment when his predecessor would have been barely getting into his, or her, stride. George Orwell remarked sometime in the 1940s that a politician is a baby at 50 and middle-aged at 75, but many a contemporary grandee is shunted off into the margins of political life almost before the nursery gates have opened before him. John Major’s career finished when he was 54; Tony Blair stood down from the premiership at 54. Nigel Lawson left the House after a bare 18 years, and it is entirely possible that David Cameron’s time in high office will grind to a halt before his 50th birthday, leaving him with another 30 years of active life to pursue.

But there is more to it than a parliamentary tenure that would strike such behemoths of a bygone generation as Sir Peter Tapsell, now retiring after a House of Commons stint that began as long ago as 1959, or the late S O Davies, who may well have been as old as 92 when he died in harness in 1972, as indecently short-lived. Another is the fact that to any student of human quiddity – the straw from which most biographical bricks are made – the specimen modern politician is a much less interesting figure.

A Well-Rounded Life might seem an odd sub-title for the biography of a late-20th-century statesman who will be remembered for his decisive impact on the mores of the 1960s but it is curiously appropriate for a man who also served as Chancellor of Oxford University, President of the Royal Society of Literature and was once awarded a decoration by the President of Senegal largely because of his knowledge of Proust.

And if Jenkins was himself a fascinating man, then he operated in an era when politics itself had a fascination which, generally speaking, it does not now possess, when the parliamentary chamber was genuinely adversarial and when the country seemed to be divided on ideological lines rather than being separated into political factions who, notwithstanding degrees of emphasis, believe more or less the same thing.

To go back to my dining-room bookcase, by far the greatest number of items relate to the 1970s and 1980s – a time in our national life when the latest late-night vote by the Labour Party’s National Executive Committee or the Union of Wheeltappers and Shunters could seem an event of world-shattering importance.

Naturally, there is nothing that modern politicians can do about this change in historical circumstance, but they might care to reflect that their essential dreariness stems, by and large, from the rise of the career politician that has been such a feature of the last 20 years: the young man or woman interested in nothing but getting a seat in parliament, who studies politics at university and then proceeds by way of a research job and a post as a ministerial aide to a safe seat. Jenkins, of course, was a career politician, as was Anthony Crosland, and Margaret Thatcher, but each of them in their various ways, had a life beyond their professional straitjacket, and one of the things that makes Mrs T interesting as a person and a biographical subject is her ability to remember lines of Larkin’s verse when poet and Prime Minister first met.

There is a wider implication in all this, that goes beyond the somewhat circumscribed world of London SW1. If literary biography, too, is in decline it is because, with certain exceptions, the modern writer merely grows up, studies creative writing, goes on to teach it at a university and writes books, whereas his or her distinguished predecessors travelled, intrigued and had bullets shot through their throats in the Spanish civil war.

Meanwhile, Roy Jenkins: A Well-Rounded Life is shaping up nicely as my Sunday afternoon treat – and, judging by its length, for several more Sunday afternoons beyond this. But it would be a very sanguine reader who imagined that, half a century from now, Ed Miliband will get the same treatment as worldly, Proust-reading, vintage-quaffing Woy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies