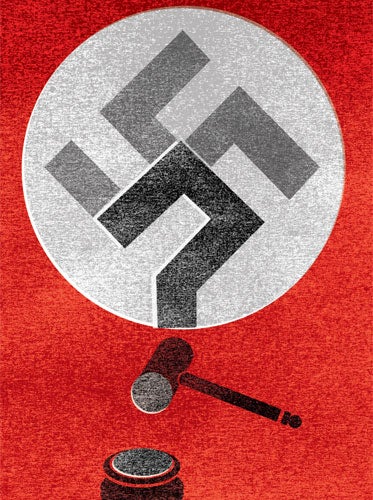

Matthew Norman: Justice vs Mercy: the impossible conflict behind Demjanjuk's trial

The question is not whether he's guilty, but if justice is served by trying him now

The trial in Munich of John Demjanjuk, already the source of as much anguished moral perplexity as any in memory, became even more unsettling on its postponement yesterday. The decrepit old man accused of herding almost 30,000 Jews into the death chambers of the Sobibor camp had developed a fever resistant to medication, the judge accepted, and was unable rather than unwilling to appear in court.

And so the doubts as to whether a gravely ill geriatric should be standing trial at all further intensified. Both the arguments and counter-arguments are so persuasive, it seems to me, that one is perfectly capable of supporting both with equal conviction at the same time. I am, anyway.

Reading the testimony of relatives of Mr Demjanjuk's alleged victims, seized by the Gestapo in Holland and instructed to pack their best shoes for their final journey to Nazi-occupied Poland, it feels inexcusably detached and effete to cite the passage of time and physical decay as reason to spare an ailing 89-year-old from being confronted with and punished for his past.

"I promise you I'll be strong, and I'll definitely survive," wrote Emmy Salomon to the friend charged with caring for her husband and small son, in a letter she threw from the train and later posted back to Amsterdam. She was gassed by exhaust fumes in Sobibor four days later, possibly bundled into the chamber by the hands hidden beneath an orange blanket as their owner lay headlong on a stretcher listening to her son recite those words.

Also possible is that the Ukrainian-born Demjanjuk is innocent. Already acquitted in 1993 by Israel's Supreme Court, on appeal after being sentenced to hang, of being Treblinka's monstrous "Ivan the Terrible", natural justice insists he be convicted before we assume his guilt. However heart-rending the posthumous accounts that reduced those in court to sobbing, they have no bearing on what appears, legally speaking, to be primarily a matter of identification and a hugely hazardous one at that more than six decades after the event. Were he convicted even in part on the emotional impact of such testimony rather than conclusive evidence, this would constitute a form of victims' justice scarcely less reprehensible than victors'.

The greater questions than that of his guilt, however, are perhaps whether justice of any kind is served by trying him now, a few months short of his 90th birthday and apparently close to death; and if so, whether the desire for justice or for vengeance is the paramount motive for the trial.

One central plank of Mr Demjanjuk's defence is that he is a victim himself. While this looks like moral equivocation taken to obscene lengths, it raises some disturbing questions. An inmate of the German concentration camp at Trawniki after being captured with the Red Army, he more than likely suffered brutality at the hands of his captors. Of course nothing could begin to excuse what allegedly followed, but if he later volunteered to be a camp guard through fear for his life, it might partly explain it. The instinct for survival is of course far the strongest known to mankind, and turns angels into devils. Which of us has the imagination to state with absolute certainty that we would opt for death over carrying out even the most unspeakably wicked of orders? I am depressingly aware that I wouldn't know the answer until the moment that choice had to made.

Whether the Nuremberg rules can be fairly applied to such a minuscule cog in such a gargantuan engine of genocidal mania seems as opaque as whether Mr Demanjuk was a sadistic brute or an obedient drone made compliant by terror. If the latter, what purpose can there be in inflating so ineffably minor a figure into probably the last of the major Nazi defendants?

The purpose, you might argue, is a duty to history. After migrating to the United States in 1951, Mr Demanjuk worked as a mechanic at a Ford plant in Ohio, and you know what his boss thought of history. But it isn't bunk, is it? "The history of the world," wrote Frederich von Schiller, "is the world's court of justice," and by this superior definition it behoves the world to do justice by revering even its most excruciating history above the humane urge to show clemency to a stricken old man.

Abraham Lincoln, who knew something about racial persecution, disagreed. "I have always found that mercy," said that greatest of Presidents, "bears richer fruit than strict justice." The modern history of South Africa, which 20 years ago seemed destined for an anarchic bloodbath but chose reconciliation over the entirely just craving for revenge, seems to bear this out.

Then again, nothing from the darkest chapters of human history – not apartheid, not slavery, not even other genocides – matches the Holocaust for unimaginable horror. What sets it apart is not the number killed or the insanely evil intent of the killers, but the clinically industrial methodology of the killing that has left in its wake a sense of unquenchable outrage. It would be a grotesque outrage itself if ever that were quenched, and if this trial played some part in maintaining it one might be less uneasy about the sight of so pitiful a specimen standing trial – lying trial, more accurately, on his stretcher – and seeing out what days remain to him in a cell.

However, one senses no fierce public interest. Those following the case, you suspect, will already be familiar with the peerlessly gruesome details of the Holocaust, and if you polled a random sample of 1,000 at a train station, I doubt more than 100 would even recognise the name of John Demjanjuk. Those paying close attention will learn nothing new. Those ignoring it will learn nothing.

Meanwhile, if Germany seeks some kind of expiation by trying a non-German national who committed no crime on German soil, it will hardly remove the stain of its shockingly laissez faire attitude to punishing infinitely more senior and viler Germans in the decades after the war.

Yet for all the grave suspicion that the trial is political and that any conviction would be unsafe, for all the worry that Mr Demjanjuk's frailty might induce sympathy where none is merited, and despite the concern expressed by David Cesarani in Wednesday's Independent that a lenient sentence will make a mockery of the case while a stiff one will look needlessly cruel, how can anyone hear Mrs Salomon's letter without believing he should return to that dock on December 21, on life-support if necessary? What level of contempt would it show, to the six million who form history's most tragic statistic and the one who is simply a tragedy, to promote mercy over strict justice? If strict justice can conceivably be done, that is, in a case so fraught with evidential and other difficulties.

Often there are no easy answers, sometimes there are no answers at all, and very occasionally there are two directly contradictory answers as compellingly persuasive as each other. Perhaps the best to be said of this trial is that by reducing the observer to agonised bewilderment over whether it should be held at all, it faithfully reflects and reinforces the unique incomprehension occasioned in us still, and God willing always, by the episode in which it was born.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks