Terence Blacker: The wind farm myths are finally nailed

The Way We Live: Who could be surprised that a survey of those who never see a turbine reveals that they are in favour of their use?

There are few trickier conversational no-go areas in civilised, metropolitan circles than the subject of onshore wind energy. Express the view that giant turbines, while playing a part in the energy mix for the future, should not be located where they affect human lives or industrialise much-loved landscape, and invariably a glazed, defensive look will settle on the face of the listener. To liberal opinion, opposing wind farm development is the moral equivalent of denying global warming or voting Ukip.

What is most noticeable about these reactions is how often convenient fallacies which have been peddled for years by those with a vested interest in development are accepted as the truth. Even those normally sceptical about what they are told by big business or government have been content to swallow this propaganda with one easy gulp.

Yet one by one the great truths deployed by lobbyists in favour of onshore wind farms are being revealed to be no such thing. For example, we have been told for some time by government, energy companies, chartered surveyors and estate agents that a house may be a few hundred yards away from a moving, noisy structure the height of the London Eye but there will be no discernible effect on its value. That idea has just been blown out of the water by the Valuation Office, which has lowered the council tax band of affected houses because their market value has plummeted.

Then there is the downright weird argument that, for many people, giant turbines actually enhance the rural landscape. The bone-headed cliché, invariably deployed by lobbyists mounting this argument, is that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder". Evidence for the beauty of turbines always comes from those who happened to drive past some on a motorway, or saw them across a valley while on holiday, never from those who live near them.

A marginally more subtle claim is that opposition to accelerating the development of onshore wind farms comes from "a vocal minority". The argument is only true in that it is a minority of the population who have first-hand experience of them. Who could be surprised that a survey of those who never see a turbine reveals that they are in favour of their use? There is no more attractive solution to the energy crisis than one which has no personal impact.

Probably the most obvious of the fallacies concerns efficiency. No one argues that turbines produce power. The question is whether their relative inefficiency is worth the impact on the countryside, the quality of life of its residents, and the billions in subsidies and the planning process. In years to come, these and other officially endorsed distortions and fallacies will be exposed.

One day, people will marvel that so much self-serving propaganda was accepted without question by quite so many people.

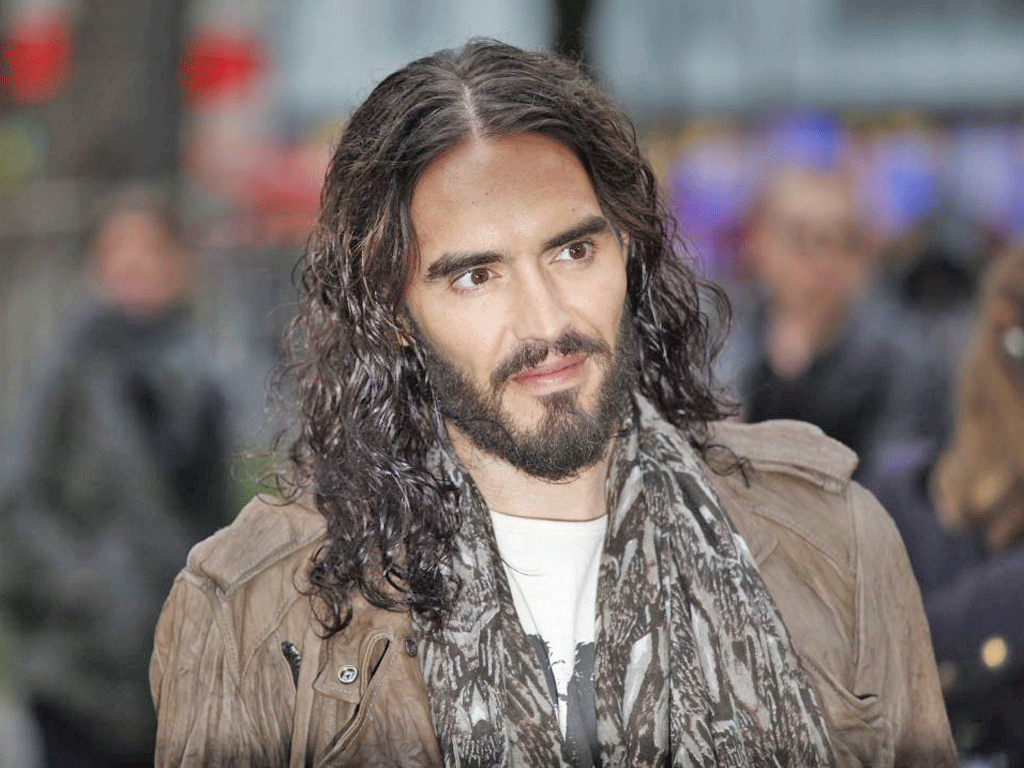

Russell Brand goes from zero to hero in less than four years

There is this to be said for the merry-go-round of fame and reputation in 21st-century Britain. If glory is short-lived, then so is shame. Four years ago, the gamey comedian Russell Brand was reviled in the press after he had, with Jonathan Ross, made an unpleasant prank call to a much-loved veteran actor. For months, he was the unacceptable face of celebrity: a heartless, leering bully who inflicted embarrassment on a sweet old man. He felt obliged to resign from his radio show, and issued a grovelling apology.

Now he is back, refreshed and redeemed. Married and divorced (public heartbreak is never bad for the image), he is lovingly interviewed in magazines and will, it is reliably leaked, play a major part in the closing ceremony for the Olympics, singing "Pretty Vacant" with French and Saunders. One moment a hate figure, the next a national treasure: can there be a more perfect symbol of the new Britain?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks