What we know about coronavirus now is very different to what we thought at the beginning

As a former medical adviser in four administrations, I recognize the position we're in now. During the emergence of HIV/AIDS, we also thought we'd find a vaccine soon

As infection and death rates from Covid-19 soar and stories of despair and health inequities abound, I'm having deja vu to my days as a medical student at NYU and a resident and fellow at San Francisco General in the beginning of the HIV/AIDS pandemic — another RNA virus which transformed the medical landscape.

So much we didn't know when a new disease descended upon our shores. Patients presented with an acute illness who would then feel better, but still be infectious, then progress to a chronic infection and full-blown AIDS and immunosuppression. The meds, some at too-high doses, caused severe side effects. We held a cherished belief that a vaccine was around the corner.

Packed HIV clinics and hospital admissions for AIDS complications were a significant part of my training. This all sounds familiar today, right down to the opening of specialist Covid-19 clinics across the country. New doctors coming of age will experience what my colleagues and I faced so many years ago.

The uncertainties on how Covid-19 is transmitted harkens back to the days of HIV and the questions we had about whether you could get it from just touching someone or a surface. Now, as the novel coronavirus ravages populations across the globe, fear and uncertainty about what to do and not to do to protect ourselves fill our thoughts and alter our behaviors — or at least the behaviors of some of us.

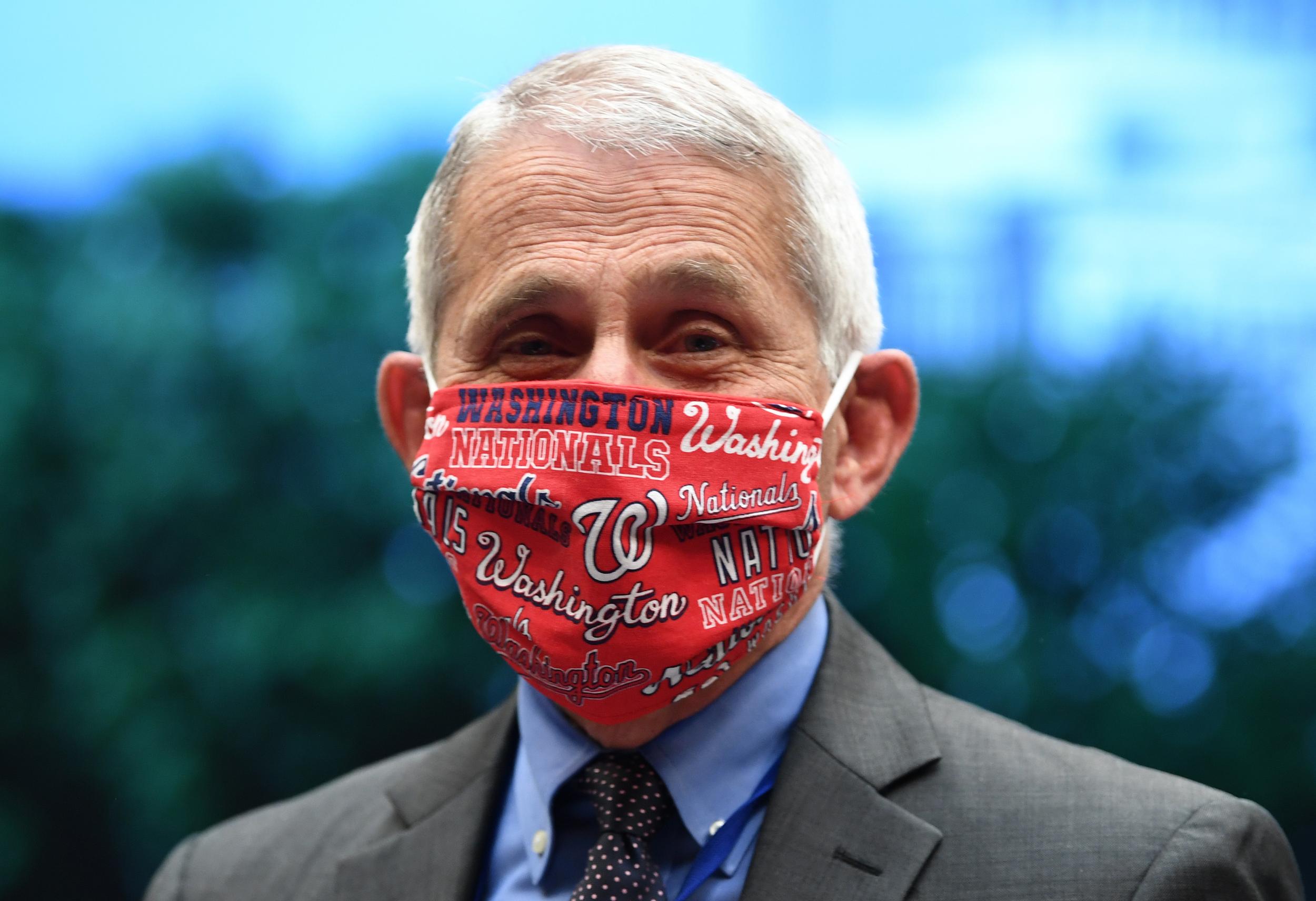

In the early days of HIV/AIDS, we tried to educate the public and our peers about safe practices and to mitigate fear and prejudice. It was a huge challenge. I recall hearing Dr Fauci share these messages, much as he is doing today. It took a long time for the public to understand that HIV couldn't be transmitted by a hug or to understand that this wasn’t a disease which only affected gay men. Children who had been infected through blood transfusions or by maternal-fetal transmission faced abhorrent discrimination; the prejudice faced by the LGBTQ community is now well-known and shameful.

Through the Ryan-White Act and active educational efforts, the public began to understand the nature of HIV. But it took time — lots of time — and fervent activism from advocates fighting quite literally for their lives.

We are now seeing patients infected with Covid-19 present with new and more severe symptoms weeks and months after they tested positive for the virus, and even for antibodies. Is this a chronic form of the disease due to re-activation of the virus or an immune reaction in overdrive? Or is it due to a new infection primed by the first one? We just don't know. Much like the early days of HIV, every patient provided a new snapshot of a virus which we would need to learn to live with and adapt our behaviors to survive.

Chronic Covid-19 may impact every system in the body as evidenced by shortness of breath, chest pain, body aches, fatigue, rashes and memory impairment, among many other symptoms — and it could be a very serious consequence of infection for people of all ages. Again, just like what we saw in the beginning with HIV, we don't know the cause of these new symptoms, but we do know that patients are suffering. On a positive note, we can take basic steps to slow down the spread of this disease just as we learned to do with HIV.

We need to do a better job today of educating the public about the fact that as information evolves, our policies and practices need to adapt. For example, the public was told to not wear a mask or face covering early on. Now that message has been reversed as the data has confirmed that they can decrease the spread of viral particles. Yet, there are some in leadership and in the public who are unwilling to accept this fact and to pivot to new policies and actions. We need to make it clear that as new data becomes available, it’s best to respond and act accordingly — that is the scientific method at work.

Bottom line: we now have the facts on one critical issue, and that is that masks or face coverings work for all of us. Perhaps, if people fear disability for a long time or the rest of their lives, they will cover up.

It is time for all nations to mandate that masks or face coverings be worn in public at all times — that message could unify the world and save countless lives and economies. It took decades for us to learn how to live with HIV. We don't have that gift of time with Covid-19.

Saralyn Mark is a former Senior Medical Advisor to the White House, HHS and NASA, and the author of 'Stellar Medicine: A Journey Through the Universe of Women's Health'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks