Complacency about Covid has replaced common sense

Editorial: Covid is a formidable enemy, and in order for it to be beaten it will take more than one weapon – the vaccines – as powerful as they might be. We need to do much more, and do it now

As families and the hospitality industry prepare for what should be the first mostly “normal” Christmas since 2019, the question is whether it will be cancelled – and if so, when. The risks are certainly increasing, with the level of infections across Europe climbing so steeply that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has warned of another half a million unnecessary deaths from Covid by March.

The WHO is “very worried” about the trends. Much of the concern derives from disappointingly low vaccination rates in some countries, the lack of vaccination among younger people in many places, and a sense of complacency that has taken hold as the pandemic has faded from headlines. Now, though, governments across the continent are being pushed into imposing restrictions on freedom, compulsory vaccination and lockdowns.

Vaccination can, in the long term and with complete herd immunity, protect communities completely, to all practical purposes, from infectious diseases – but participation has to be very high indeed. Vaccines can and do reduce infection, illness, deaths, and pressure on health services, even without herd immunity and eradication, but if vaccination rates are as low as they have been in parts of Austria, for example, then the defences will be much weaker.

The consequence, in Austria, is that vaccination has had to be made mandatory. Had Austria not been infected with an unusually virulent strain of conspiracy theory about vaccines, the country might not now be contemplating the deeply problematic policy of compulsory vaccination.

Measures such as mask-wearing, social distancing, working from home, lockdowns and vaccine passports are being introduced in European countries such as Denmark, France, Sweden and Germany with such urgency because their governments realise the risks, from bitter experience, of doing too little too late.

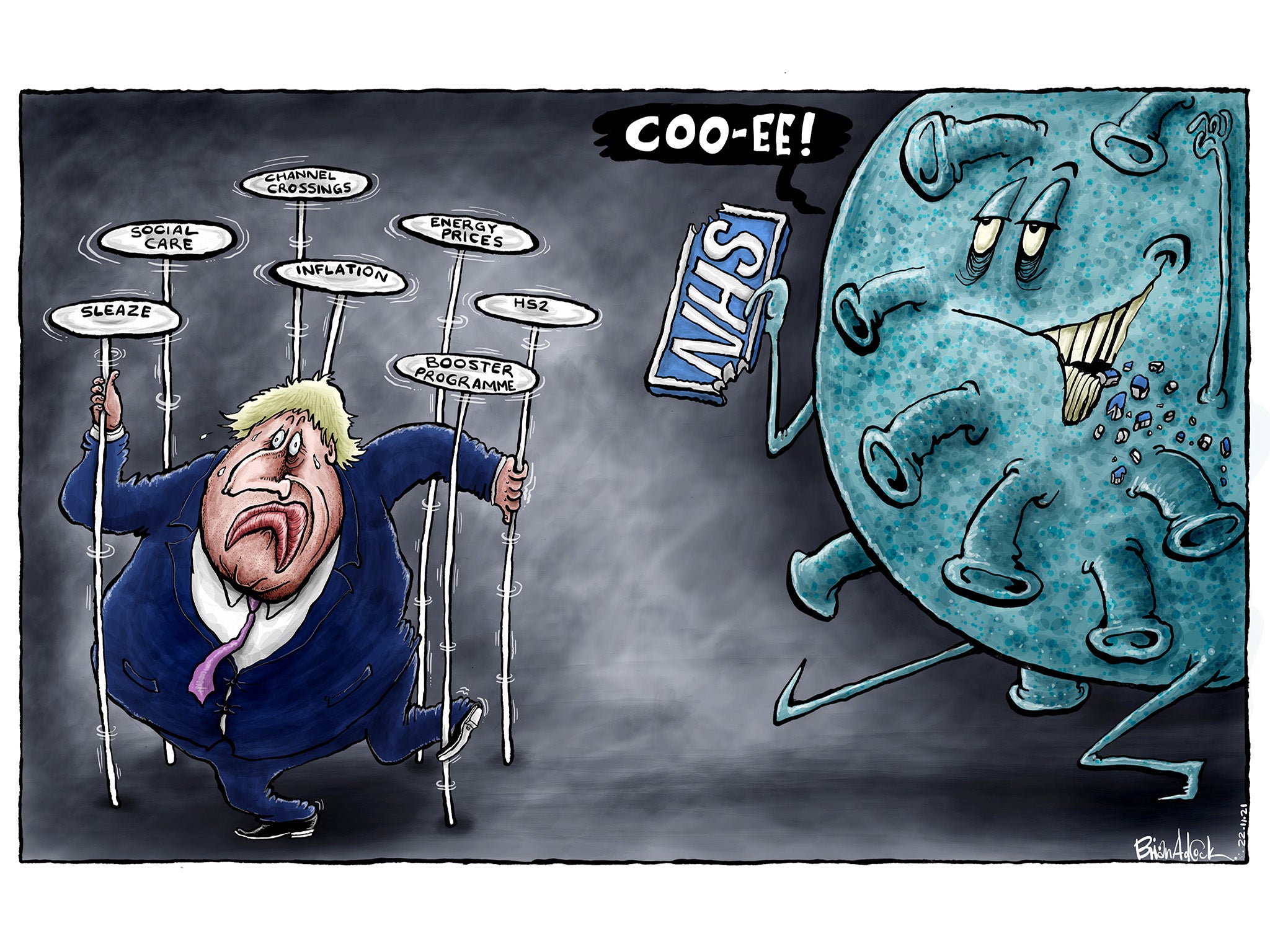

In Britain, though, complacency is king. Sajid Javid, the health secretary, says that England (the rest of the UK being more vigilant) is sticking to plan A, which is to do nothing beyond encouraging people to take the vaccine and get a booster jab. Given Britain’s early successes and relatively high rates of take-up, that might not be such a bad plan, yet the numbers taking the booster are just too low, coupled with the slow progress in vaccinating children, to be able to ensure that Christmas is “saved”.

Fortunately, the government has a plan B. This includes measures such as the mandatory wearing of face-coverings, working from home, and vaccine passports or testing to gain access to venues. Unfortunately, the government seems extraordinarily reluctant to implement the fallback plan. The public can only assume that the scientific advice is just about strong enough to support ministers’ stubborn refusal to take precautions, but that is a scientific judgement. Politically, given the trends in infections and existing pressures on the NHS, if Christmas is to be saved this year (and many lives with it), then some modest constraints on our liberty and social interaction need to be introduced now.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices newsletter by clicking here

Only a year ago, with winter flu, respiratory illnesses and another Covid spike approaching, Boris Johnson reassured the nation that things were similarly under control. Tickets were booked, giant turkeys ordered, the mince pies baked, the presents bought. Then, at almost the last minute – 19 December in fact – Mr Johnson had to hold a press conference and declare: “Given the early evidence we have on this new variant of the virus, and the potential risk it poses, it is with a heavy heart that I must tell you we cannot continue with Christmas as planned.”

They were not vote-winning words, and his authority and popularity now are lower than they were then. If he wants to spend time at Chequers this Christmas looking forward to another year or more in office, he needs to avoid another U-turn like that.

This year, Mr Johnson might argue, things are different because of the vaccine programme. Yet the unnerving fact is that the protection offered by the vaccines administered with such speed in May, June and July in the UK is beginning to fade – and children are still a powerful vector in the infection of older relatives. What was once such a British success – the rapid rollout in the first months of 2020 – is now turning into a fresh vulnerability. Covid is a formidable enemy, and in order for it to be beaten it will take more than one weapon – the vaccines – as powerful as they might be. We need to do much more, and do it now. Putting on a face-covering doesn’t seem that much to ask in the circumstances.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks