The final chapter of Muhammad Ali's life was the most poignant – he became a martyr

Muhammad Ali became something else in the final act of his life. He became an uncomplaining martyr; an increasingly statuesque testament to the capacity of the human spirit to endure

The problem for F Scott Fitzgerald when he said “there are no second acts in American lives” is that he never lived to see Muhammad Ali. In the life of this strong challenger for the title Most Remarkable American of the 20th Century, there were four acts.

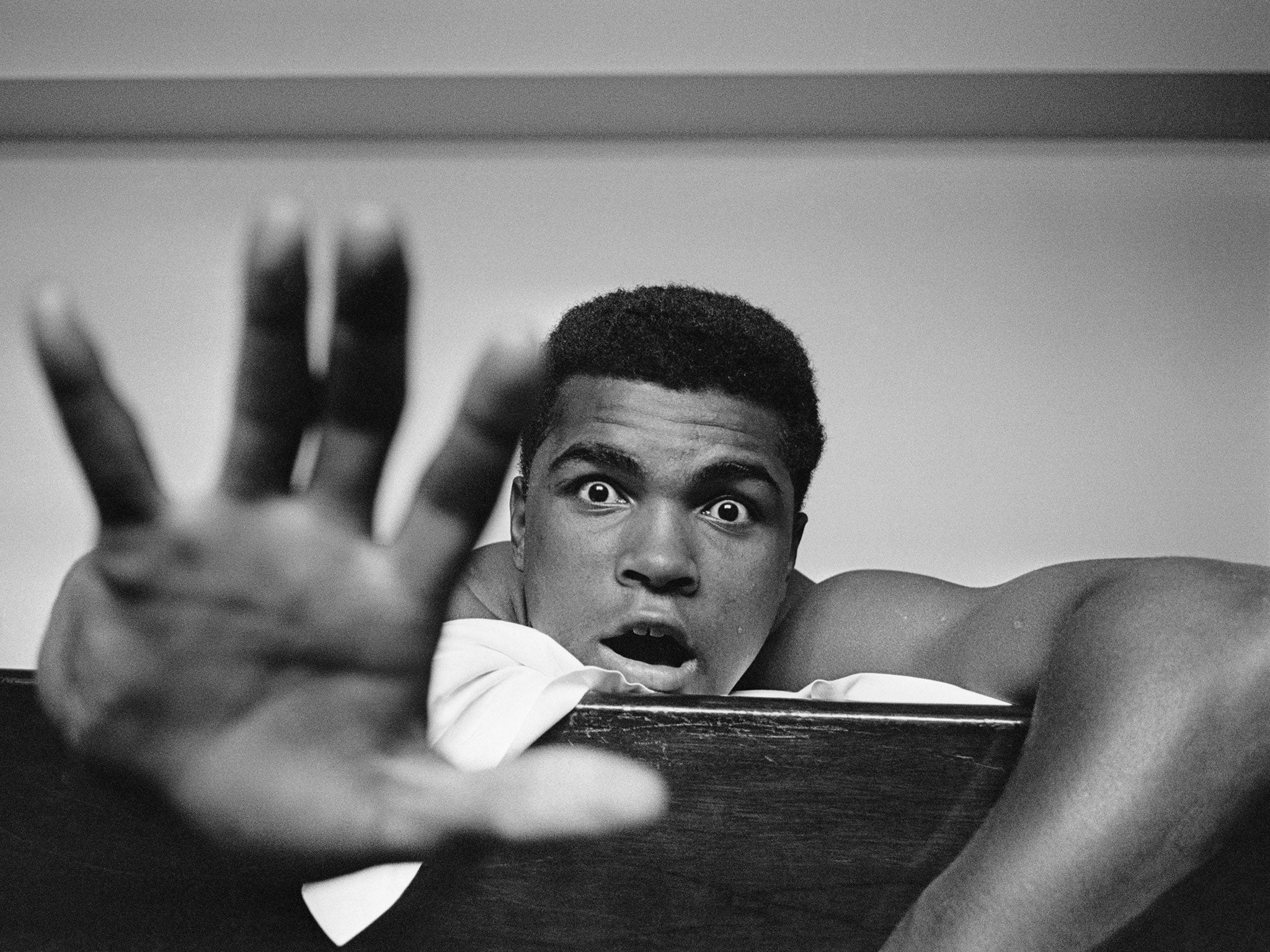

The first was his rise from the poverty of his Kentucky upbringing, as the grandson of slaves to the heavyweight champion of the world. In 1964, a rank outsider of 22, he stretched belief for the first time by dismantling Sonny Liston.

The second act began four years later when he matured into a political figure. His rejection of the draft to fight in Vietnam saw him banned from boxing at his peak. His rejection of his slave name, Cassius Clay and entry into the Nation of Islam transformed him into an emblem of the civil rights movement.

The third act followed the Supreme Court’s 1971 decision to overturn his draft-dodging conviction, freeing him to return from exile to dominate the most golden heavyweight era.

It would be cliché to describe the fourth act as the bravest. But he bore the decades of physical failure, when a central nervous system disorder, possibly Parkinson’s, brought on by blows to the head, gave the Ali Shuffle a distressing new meaning, with unimpeachable fortitude and dignity.

With Elvis Presley, another product of the dirt poor American South who shook up the world, people debate which version (slender pelvis-waggler or portly Vegas crooner) they prefer.

With Ali, there is little argument. The first, second and fourth acts all had their magnificence, and his political significance as a fighter against the poisonous orthodoxies of his age cannot be overstated. But for anyone of my age, growing up in the 1970s when the only Parkinson that concerned him was Michael (in the memory, Ali was a bedazzling chat show presence, almost weekly), it was the third act that made him the greatest.

A few days ago I was chatting with a friend about our top 10 most treasured sporting memories. There was much debate about numbers two to 10, and none about the number one. The Rumble in the Jungle transcended sport in a way nothing else has or will. Some events become gradually imbued with grandeur as decades pass. Even as it unfolded in October 1974, Ali’s meeting with George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), felt more like a tale from Homer than a boxing bout.

No sport event had such a long and frenzied build up, and none was as starkly Manichean. Foreman would have a second act of his own, reinventing himself as cuddly salesman of that lean, mean fat-reducing grilling machine. But back then he was as brusque and unlovable as he was murderously powerful. Few gave Ali a chance. Many genuinely feared for Ali’s health, mapping out the fastest route from the ring to hospital. Some thought he would die.

The rest is history – and real history, somehow, rather than the ersatz sporting kind. With the same raw courage he had shown against Smokin’ Joe Frazier in the incomparably brutal Thrilla in Manila, and would later display in taking terrible beatings in his decline, Ali exhausted Foreman with his “rope-a-dope” tactic. Finally, dancing off the ropes late in the eighth, he staggered the seemingly unbeatable Foreman with a lethal combination. He even produced the most glorious moment in his entire career by doing nothing. Rather than finish the job as Foreman began to fall, he stopped himself from throwing the shot for fear of ruining the aesthetic. Not long ago, I was telling a 14-year-old nephew, who has just started boxing, about “the punch Ali never threw”.

As if the David vs Goliath flavour wasn’t biblical enough, a melodramatic thunderstorm lit up the Zaire skies seconds after the late BBC commentator Harry Carpenter blurted his memorably astonished, “Oh my God, he’s won the title back at 32!”

More even than David Bowie, who also journeyed from being a perpetual outsider to an establishment beloved, Mohammed Ali towered over the 1970s. A man of preposterous beauty in the ugliest of sports, a brilliantly funny self-parodist whose underlying seriousness of purpose was never in doubt, he illuminated the decade with relentless candescence.

And then the lights began to go out. I remember the night that possibly started the process in gloomy clarity, lying in a sleeping bag, loaded up with caffeine pills to stay awake to listen to an unbearably poignant commentary. Larry Holmes, his old sparring partner, gazed imploringly at the referee to step in to save Ali from the monstrous punishment from which he was too eternally the warrior to excuse himself from, by staying on his stool as Liston had against him.

A few years and more hidings later, the first signs of illness were unmistakable. A man better known than any for his speed and coordination began to slow and lose motor control. A man more revered around than anyone else for the quick fire brilliance of his speech started to mumble and slur.

As the illness turned down the luminescence, the legend grew brighter. The demigod who had challenged and overcome Sonny Liston and fought against racial segregation, as loathed in his early career as he was adored after returning from exile, became something else in the final act. He became an uncomplaining martyr; an increasingly statuesque testament to the capacity of the human spirit to endure.

Any temptation to regard that fourth act as the most admirable is worth resisting. Millions cope with physical conditions such as his with similarly humbling stoicism. If such flaws as his race-baiting taunting of Liston and Frazier prevented him being uniquely perfect, Mohamed Ali was perfectly unique.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies