Ghislaine Maxwell’s trial feels disturbingly familiar

If you’ve followed even just one sex crimes trial, you’ll know

The women never have names. Not their real ones, anyway. When the time comes to stand in the courtroom and relive their past traumas, a lot of them choose pseudonyms. They do it to protect their present and future selves. They do it to preserve their careers, their personal lives. They do it so that people won’t be able to look them up. They do it because they know the world isn’t kind to those who say they were the victims of sexual crimes.

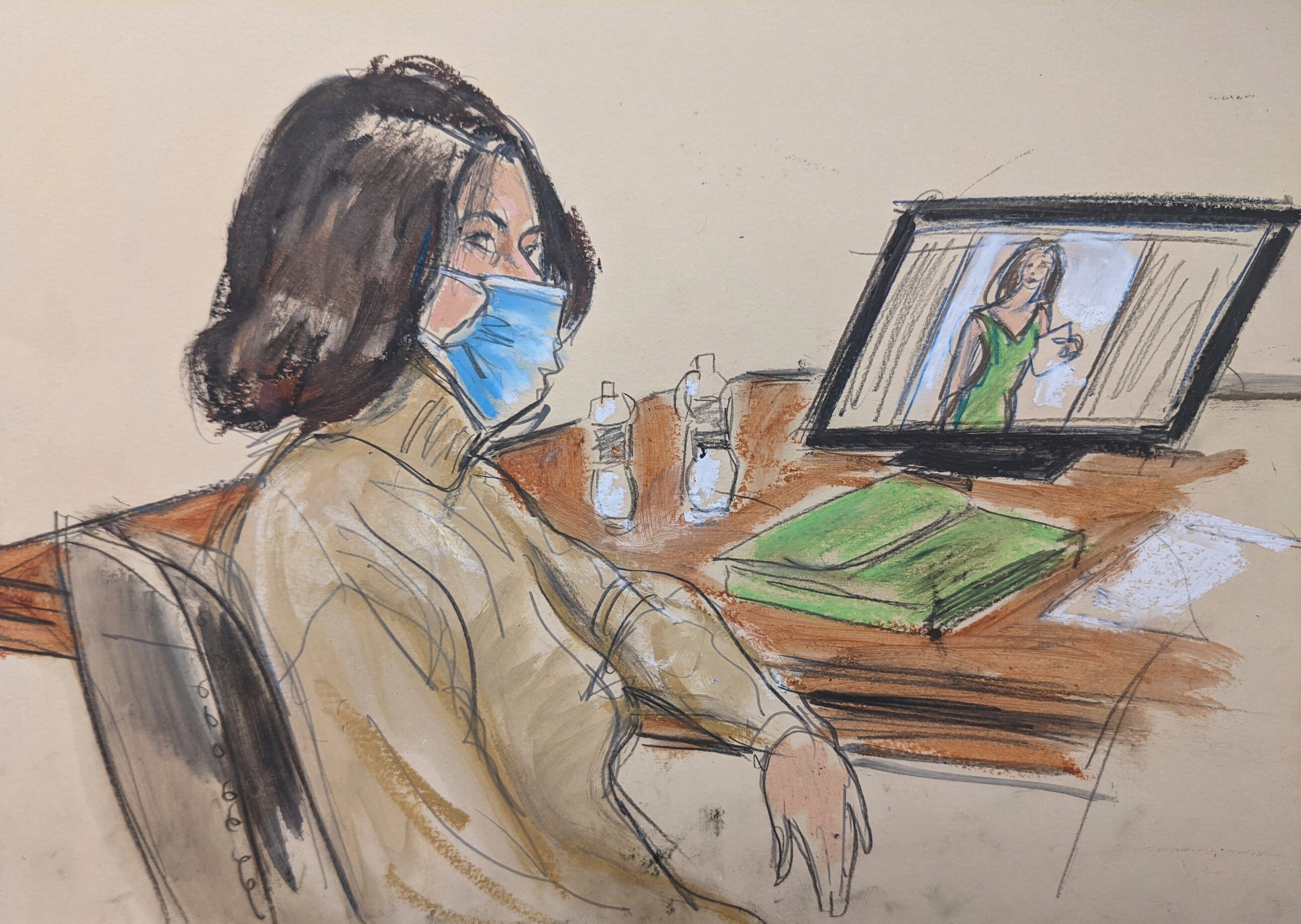

These are the women involved in Ghislaine Maxwell’s trial, which started this week in New York City. Maxwell is accused of recruiting and grooming four underage girls for Jeffrey Epstein to abuse between 1994 and 2004. She is facing eight counts of sex trafficking and other crimes, including two counts of perjury that will be ruled on separately at a later date.

As I followed the first five days of the trial in Manhattan federal court, I was struck by how disturbingly familiar the proceedings have felt so far. I don’t mean this in a diminutive way; on the contrary, the trial is the culmination of a multi-year process, which almost began in the 2000s when Epstein was first apprehended. Alas, he was offered a sweetheart deal and roamed free until 2019, when he was arrested and charged with sexually exploiting and abusing dozens of underage girls. Epstein died by suicide while in custody the following month. So, yes, it means something to see Maxwell have to answer for her alleged actions in a courtroom.

One of the witnesses involved in the trial spoke under the pseudonym Jane – because, the Associated Press noted, she wanted to “protect her 22-year acting career”. It wasn’t hard to understand why Jane thought testifying under her real name might endanger her career. We’ve seen it all before. We know how unkindly people treat women who speak.

If you’ve followed even just one sex crimes trial, you’ll know. For me, it was Harvey Weinstein’s criminal trial, which ended with him convicted of a criminal sex act and third-degree rape in February 2020. My last day of “normal” work before most of New York shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic was spent in court, watching Weinstein be handed a 23-year prison sentence.

It is a function of American criminal trials that any witness put on the stand by the government can then be cross-examined by the defense attorneys. I understand why this happens. If the government gets to make its case, so too should the defense. And it’s not the existence of this cross-examination that unnerves me; it’s the way it tends to unfold in cases like Weinstein’s or Maxwell’s. In both cases, the defense has served up similar arguments, seeking to discredit the women who say they were victimized, attempting to cast doubts on their testimonies, and trying to paint them as interested parties who supposedly seek money or other benefits.

It happened as early as Monday, when Maxwell’s lawyer told the court that “this case is about memory, manipulation, and money”, claiming that “in this case you will learn that not only have memories faded, but they have been contaminated by outside information”.

It happened on Tuesday, when Jane testified that Maxwell was often “in the room” when Epstein abused her. During cross-examination, AP wrote, defense lawyer Laura Menninger “immediately attacked” Jane’s credibility, “asking why she waited over 20 years to report the alleged abuse by Maxwell to law enforcement and why she brought two personal injury lawyers along to her first meeting with the FBI”.

It happened on Wednesday, when cross-examination continued on a similar note, and it happened on Thursday, when a defense lawyer tried to undermine a psychologist’s testimony about how abusers sometimes groom their victims, by pointing out that sometimes adults simply do nice things for children, not to groom them, but just out of the kindness of their hearts.

A defense attorney’s only duty is, of course, to their client. But trials are public, and conversations inside the courtroom have an impact outside the courtroom. And as long as lawyers aggressively seek to discredit women who say they were victims of sexual crimes, it will be easier for people to do it outside the courtroom too.

If the justice system doesn’t offer any other way to protect a defendant’s interest than to treat alleged victims of horrific crimes in callous ways, then that is, to me, a problem. And the fact that it keeps happening, in what has become a shockingly predictable way, doesn’t bring me much comfort either.

There has got to be a better way to go about this. As long as this is the blueprint for the prosecution of sex crimes, victims will be reluctant to come forward, afraid of the consequences. Surely this isn’t the most direct path to justice.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks