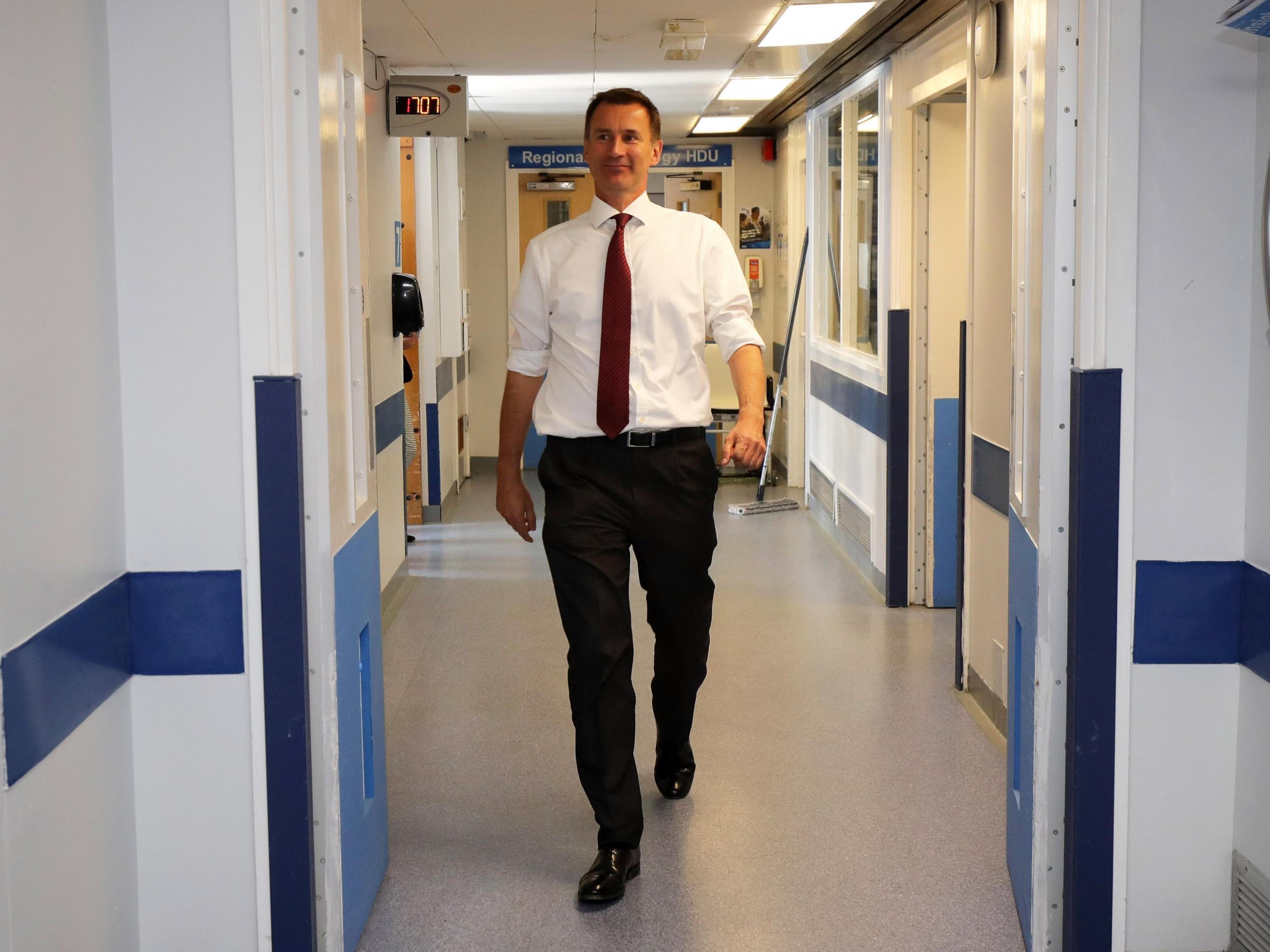

Jeremy Hunt is now the longest serving health secretary since the NHS was created – so here’s his report card

Occasionally Jeremy is mentioned as future leadership material. If so, then the precedents are not encouraging for him

REPORT CARD FOR JEREMY HUNT

Overall assessment: 6/10: Jeremy tries hard but doesn’t always live up to his promises. He has been health secretary for longer than any of his predecessors, which is a remarkable achievement in itself, and patients still view the NHS with affection and respect. An attempt to move him to the business department in a reshuffle in January failed when he simply said “no” to Theresa May.

Most NHS patients are extremely satisfied with their world class and highly professional treatment. There is, though, room for improvement.

Interested parties should also note that Jeremy has only been responsible for the NHS in England, as a devolved power, and has been unnecessarily and quite tediously, rude about what he says are the problems of NHS in Wales.

1. Health Service Spending: 6/10

Jeremy, it seems, has managed to get as much out of the Treasury as he can, and he has at least approximated to the Conservatives’ manifesto commitment to increase real-terms spending (a hotly disputed topic). In any case, the NHS has certainly come off better than many other areas, such as student finance or defence.

Health service spending, in absolute real terms (i.e. as a cash sum adjusted for retail or consume price inflation) has never been higher.

As a proportion of national income, it is also at a high level historically, but has, more or less, peaked since about 2010. Under the program of austerity since then, which was in turn necessary, some argue, to restore the public finances, the NHS has been on a tighter leash.

Whichever benchmark is chosen, NHS spending has failed, once again, to keep up with neither the public’s expectations, demographic trends (both the growth and ageing of the population) or new treatments and technologies. Of course, an even larger proportion of the national income could be spent on the NHS, so a sense of proportion is required: but, even so, there has been an impact on patient care which many feel is unreasonable.

According to a report by The Independent and respected Institute for Fiscal Studies last year, UK public health spending grew in real terms by an average of 1.3 per cent per year between 2009-10 and 2015-16. This is substantially below average growth of 4.1 per cent per year between 1955-56 and 2015-16. Spending growth under the coalition government was the lowest five-year average since records began.

Internationally, total UK health spending, including both public and private expenditure, was in line with the unweighted EU-15 (the older, wealthier members) average (9.8 per cent of national income) in 2015.

2. Future Plans: 2/10

With the 70th anniversary of the NHS approaching on 5 July, there was some suggestion that it would be a fine moment to offer a grand long term funding plan for the NHS. This, though, seems to have run into some political difficulties, and Hunt has failed to convince the Treasury to part with sufficient funds to place the NHS beyond financial strain.

The IFS and Health Foundation think tanks recently stated that the growth rate for health spending (real terms), which has been just 1.4 per cent a year (2010-17), will have to more than double to between 3.3 per cent and 4 per cent over the next 15 years if government pledges, such as bringing down waiting times and increasing the provision of mental health services, are to stand any chance of being delivered. They also say that to finance this increase the government would “almost certainly need to increase taxes”. Hence the reluctance under a Conservative-run Treasury.

The squeeze on pay has led to many vacancies going unfulfilled, and reduced support for nursing training has also had a detrimental impact. Brexit, too, could make life more difficult for the NHS in finding skilled and unskilled staff.

3. Public Image and Political Management: 6/10

It is true that there have been perennial crises, especially at Christmas, and scandals or problems over issues such as breast cancer screening, botched PFI deals, pay, waiting time targets and the “Seven Day NHS” scheme. Jeremy’s name was also embarrassingly mispronounced by James Naughtie on BBC radio, possibility as a result of his approach, perceived by some as uncaring. Jeremy has been painted by Unison and pressure groups as the personification of a Tory plot to “privatise” the NHS, starve it of resources, and generally run it down.

His worst moments came during the NHS junior doctors’ dispute about new contracts (2015-16), with high-profile strikes and public sympathy for the hard working medics. Jeremy even managed to get into a scrap with Stephen Hawking. He’s also had scrapes about his parliamentary expenses and the purchase of a number of luxury flats.

Against all that, which has kept him in the headlines, Jeremy has actually emulated one previous Conservative secretary of state, Norman Fowler in the 1980s, in keeping – relatively speaking – a lid on industrial disputes and public discontent during economically difficult times.

Labour and shadow health spokesman Jon Ashworth have a substantial lead as the best party for the NHS of something like 10 to 20 per cent in the polls (depending on which organisation), but the gap was running at much more than that during the Thatcher and Major governments (50 per cent plus in 1995, for example).

4. Social Care: 2/10

By common consent, the system for social care provision is a mess, and, if anything, made worse and more confused by Theresa May's proposals in the 2017 general election for a so-called “dementia tax” (which might have helped poorer families in fact, and led to a more rational and fairer approach, but which was a PR flop).

The Dilnot Commission Report (2011) and countless other weighty proposals have been shelved and government policy continues to drift. In 2016, a cross party commission led by ex-health secretaries Stephen Dorrell (Conservative) and Alan Milburn (Labour) and Liberal Democrat MP and ex-health minister Norman Lamb called for more funding and an all-party approach on social care, to no avail.

Jeremy’s acquisition of the enlarged title of “secretary of state for health and social care” in that botched reshuffle earlier this year seems to have changed nothing, and the NHS and local authorities are no more “joined up” than before. Spending and organisation are one side of a painful squeeze; increasing numbers of Britons living much longer but unhealthier lives into advanced old age the other.

To offer one striking statistic: in 1980 the number of centenarians in the UK was a relatively select club of 2,300 or so; today there are about 15,000 of us aged 100 plus; by 2040 – not so very far away – Buckingham Palace will have sent out 148,000 telegrams to people born after 1940 and still kicking around.

5. Jeremy’s Prospects (5/10)

Occasionally Jeremy is mentioned as future leadership material. If so, then the precedents are not encouraging for him. Only one predecessor as health minister or secretary has made it to Number 10, being Neville Chamberlain (1924-9), an energetic and successful reformer in the post, who then went on to enjoy a lengthy tenure as Chancellor in the 1930s.

In the past, the Department of Health has attracted some gifted and powerful personalities of all parties, including Christopher Addison (1919-21), Enoch Powell (1960-63), Keith Joseph (1970-74), Barbara Castle (1974-76), Kenneth Clarke (1988-90) and of course, and most famously, Aneurin Bevan (1945-51). None, though, quite made it to the top.

Of the Conservative incumbents, Andrew Lansley (2010-12), Virginia Bottomley (1992-95) and William Waldegrave (1990-92) probably did worst at limiting the Tories’ toxic reputation on the NHS.

Few, if any, then, prosper in the role, and it is, if you’ll forgive the expression, the job next to the door on the political hospital ward, the graveyard of careers. As Nye Bevan, referring to his Welsh constituency, once remarked: “If a hospital bedpan is dropped in a hospital corridor in Tredegar, the reverberations should echo around Whitehall”. Seventy years on, Jeremy knows the same feeling.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks