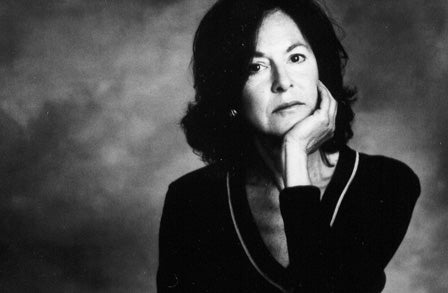

Nobel Prize for Literature winner Louise Glück is a poet to guide us through the frightening world of 2020

At a time where the impending threat of winter looms large, where death feels evermore present, the Nobel Prize committee’s decision feels something like an honouring of hope

In her poem “Ithaca”, Louise Glück notes that Odysseus lives two concurrent lives: “He was two people/ He was the body and voice, the easy/ Magnetism of a living man, and then/ The unfolding dream or image.” This duality between the self and the individual that lives in the mind of others works well as an image for the poet, who this week became the 16th woman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature – and the first American woman to do so for 27 years.

As one of America’s leading poets, Glück is hardly without recognition; she has won the National Book Award, Wallace Stevens Award, and two Guggenheim Fellowships. With 12 collections of poetry and two essay collections, she’s been writing for the best part of her 77 years, starting early with the encouragement of her parents in New York City’s Long Island.

Despite a happy childhood, the death of an elder sister before she was born cast a shadow, one that illuminates much of her writing and one of her most quoted lines: “We look at the world once, in childhood. The rest is memory.”

Memory, history and the past play important roles in her work. As with her contemporary Anne Carson – another name tipped as a potential Nobel winner – Glück finds rich inspiration in the mythology of Ancient Greece and Rome. In Meadowlands (1997), Odysseus and Penelope reveal the insecurities of a contemporary married couple. In Averno (2006), Persephone gazes into a pool “looking for the girl she was”. Through these ancient stories Glück finds new footing to explore the present, often drawing on shades of her own experience: marriage, loss, love.

Yet despite flitting from Dante, to opera, to the inner life of an earthworm, Glück resists the trappings of ornate language. In her own words: “I loved those poems that seemed so small on the page but that swelled in the mind.”

Glück is an architect of words, the richness of her poetry stems often not from what is said, but how it is built. She is a master of choreographing the reader’s eye, slipping over the end of a line only to come to a shuddering halt in the next. Her words hold what Colm Toibin describes as an “electrifying undercurrent”, steering her readers through language, both physically and emotionally. “What fascinated me were the possibilities of context,” she wrote in Proofs and Theories: Essays on Poetry, “the way a poem could liberate, by means of a word’s setting, through subtleties of timing, of pacing, that word’s full and surprising range of meaning.”

The sentence becomes “a unit”, a landscape in which even the simplest of words are given new life. Her “great task”, she writes, is “to infuse clarity with the passionate ferment of the inchoate, the chaotic.”

These structures provide a means of controlling and mediating experience, something Glück originally channeled into her own life. When she was 16, she developed anorexia and nearly starved herself to death. In interviews she defines the time as one in which she was attempting to create a new self, to find a form, but took the wrong path. In one poem, she writes: “I felt/ What I feel now, aligning these words–/ It is the same need to perfect.”

The disease disrupted her education – she attended poetry workshops and classes at Sarah Lawrence and Columbia, yet never received a degree – but as part of her treatment she was introduced to psychoanalysis, a practice that informs many of the self-reflective interrogations of her later works. There is an assertive assuredness in her voice even as she explores great doubt and uncertainty; these moments of internal questioning, of constant self-evaluation echo the thrum of interiority we live with daily. Glück puts it on the page.

The personal became a portal, a doorway through which Glück has been able to explore more expansive ideas, while in turn revealing selfhood itself as vast ever-changing terrain. “You have to live your life if you’re going to do original work,” she notes, “Your work will come out of an authentic life… if you suppress all of your most passionate impulses in the service of an art that has not yet declared itself, you’re making a terrible mistake.”

She speaks from experience: after her debut collection Firstborn (1968), she found herself unable to write, bound to the idea of what the life of a poet should look like rather than living her own. It was only when she started teaching that she found herself able to work again. “What you use is the self as a laboratory,” she notes. “I’m an opportunist – I always hope I’ll get material out of any activity. I never know where writing is going to come from.” This unpredictability of inspiration turns to advantage. “There were two years when I read nothing but garden catalogues, and that turned out okay – it became a book.” Wild Iris won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1993.

The chair of the Nobel Prize committee, Anders Olsson, has called Glück “a poet of radical change and rebirth, where the leap forward is made from a deep sense of loss”. The title poem of Wild Iris speaks of a resurrection of this kind: “I tell you I could speak again: whatever/ Returns from oblivion returns/ To find a voice”. Olsson highlights another poem, “Snowdrops”, where a flower wakes after a long winter: “I did not expect to survive/ Earth suppressing me,” writes Glück, “I didn’t expect/ To waken again, to feel/ In damp earth my body/ Able to respond again.”

Could there be a better poet to help us cope with the frightening world of 2020? Despite our losses, surely we all eventually hope to be facing life, in Glück’s words: “Afraid, yes, but among you again/ Crying yes risk joy/ In the raw wind of the new world.”

At a time where the impending threat of winter looms large, where death feels evermore present, the Nobel Prize committee’s decision feels something like an honouring of hope: a celebration of the risks of joy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks