As a former teacher, I know what it's like to be sexually harassed by pupils – and what should be done to change this

We need to empower teachers to speak up about the abuse they encounter, and push for better lessons on sex and relationships, including discussions on consent and objectification

According to a recent study by teachers’ union NASUWT, four in five teachers have been sexually harassed or bullied at school.

I’m disappointed but not surprised to hear this. When I was a teacher there were numerous incidents that made me uncomfortable and damaged my mental heath and feeling of self-worth.

Quite often it was the students who would say and do inappropriate things, but they were enabled by adults who would not pull them up on their behaviour, and in some cases just dismissed it.

I witnessed incidents in which pupils would track down teachers on social media, take their pictures and repost them to an Instagram account where they were judged on their appearance. On more than one occasion, parents looked us up and down and made comments about our age.

I had no clue who I could voice my concerns and discomfort to, and I’m not surprised to hear that teachers still feel like they can’t report what is happening.

The focus in schools is on protecting the wellbeing of the children but sometimes this can be at the expense of the staff, who are often underappreciated anyway. Parents, pupils and senior staff make it very clear that you are working for them and speaking out can feel very scary. You’re not sure you will be respected or taken seriously.

To actually deal with sexual harassment you have to let senior staff and the parents of the pupil know. That is often where the difficulty arises. Many parents are unwilling to accept that their child has been involved in something unpleasant – even something as mundane as not handing in homework, let alone harassment or bullying.

They will feed back concerns to senior staff who will try to placate them. In my case, I was cross-examined to the point where I ended up doubting my own experience of what had happened. Teachers will be asked whether they actually heard the offensive comment, if they remembered what had been said properly. Could they be confused? Do they really want to make a complaint about something so serious?

I had one pupil actively try to embarrass me in front of a class by talking about how much I must love “the D”. It was clear that they were discussing how I must love sex and penises. However, when I tried to tell a senior member of staff about what happened, I was told that I had probably read too much into things and was taking it too personally. I never spoke up about such issues again.

I have now left teaching. The lack of a safe environment and the impact it had on my mental health played a role in this. All that seemed to matter was results and keeping parents happy.

Aside from more support for teachers to speak up about the abuse they encounter, we must push for better lessons on sex and relationships, including discussions on consent and objectification.

Currently this falls under the PSHE (personal, social, health and economic education) curriculum, but the subject is rarely taken seriously and overworked teachers are often just given some PSHE classes to teach on top of their already busy timetable.

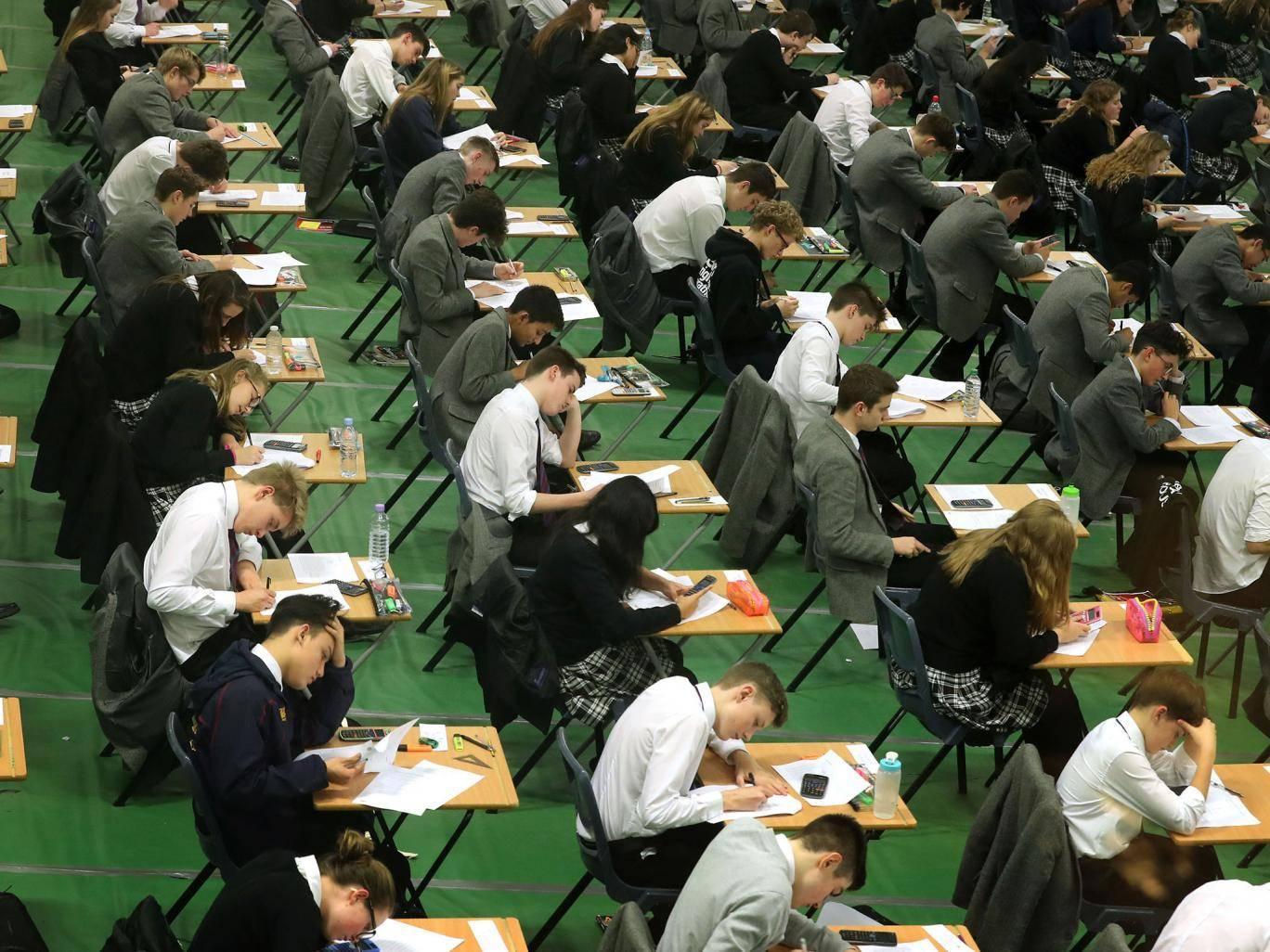

Consequently, they don’t have time to make it a brilliant hour-long learning experience. PSHE is often not graded and students may not sit any exams in it. Therefore, in school environments where results are everything it is often neglected.

In fact, in my experience, it is often the first lesson to be given up as soon as exams approach and the pressure for getting good grades means that any extra time is given over to revision. The current attitude towards lessons such as PSHE is dismissive at best and condescending at worst.

Unfortunately this approach does little to prepare vulnerable teenagers for the complexity of gender relations, nor does address any questions or concerns they may have.

If teenagers don’t get the right sex education from the beginning, then we are setting them up to fail as adults. If we truly want a fairer and more equal society with well-rounded citizens it might be time to change our priorities. Good grades are important but so is tackling sexual harassment and more needs to be done in schools to readdress the balance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks