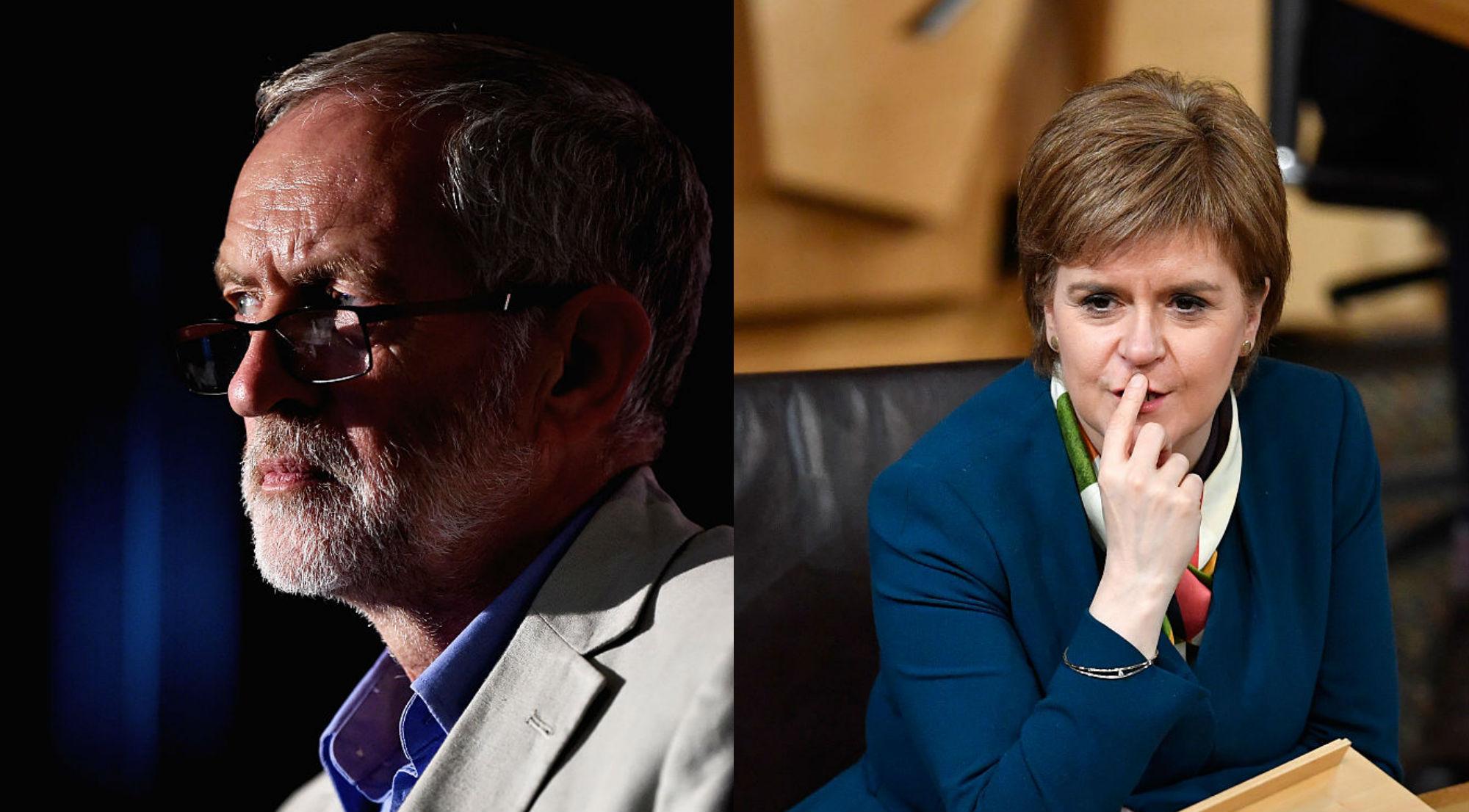

Farewell Sturgeon and Corbyn: it’s been a good week for rational politics

The departure of two divisive politicians might mean that calm, inclusive competence will prevail, writes John Rentoul

Keir Starmer condemned him, first indirectly as “the previous leadership”, and then by name: “Jeremy Corbyn will not stand as a Labour candidate at the next general election.” It was the final breach, a symbolic moment as significant as Neil Kinnock’s denunciation of Derek Hatton and Militant at Bournemouth in 1985, and Tony Blair’s pledge to rewrite Clause IV at Blackpool in 1994.

Gone was any pretence that Starmer wanted to continue with any part of the Corbyn legacy. “The Labour Party is unrecognisable from 2019 and it will never go back,” Starmer said. The news conference was ostensibly to mark the moment the Equalities and Human Rights Commission formally declared the party free of the stain of antisemitism, but Starmer chose to make it a wider declaration that the party repudiated its recent past.

That manoeuvre was not without its intellectual contortions, because the more Starmer attacked his predecessor, the harder it should have been for him to explain why he worked to make Corbyn prime minister in 2017 and 2019. Yet he was asked the question only once, and sidestepped it without much difficulty. He has some skill in the deployment of bland generalities.

Thus the message was sent out loud and clear: welcome back, Middle England, it is safe to vote Labour again.

Or, that would have been the message that would dominate the headlines if it had not been for new news from Scotland. At about the time Starmer left his lectern in London, word spread that Nicola Sturgeon would be coming to a lectern in Edinburgh to announce her resignation. The dissing of Corbyn suddenly became the less interesting political story of the day.

However, Labour disappointment at being trumped by Sturgeon was outweighed by joy at what this means for the party’s prospects in Scotland. Just as Starmer was telling Middle England it was safe to come home to Labour, the first minister was telling Middle Scotland the same thing. Without Sturgeon as leader, and with the prospect of a Labour government of the UK, some of the soft support for the Scottish National Party could swing back to Labour next time.

There is a bigger significance in the departure of both Corbyn and Sturgeon. They are both divisive politicians who advanced their fundamentalist politics at the expense of the pragmatic and unifying Labour approach.

Sturgeon seemed to acknowledge this in her resignation statement. She said that one of the reasons for stepping down was that opinions about her were “polarised” and were “becoming a barrier to reasoned debate”. She was the wrong person after eight years at the top to “reach across the divide in Scottish politics”.

That was the problem with Corbyn too, at the UK level. Separatism and socialist utopianism are similar in that they offer absolutist solutions to the frustrations of normal politics and messy compromise.

Both Sturgeon and Corbyn had a public face of benign reasonableness that belied their fundamentalism. Sturgeon posed as a tolerant social democrat, but many of her supporters were animated by anti-English sentiment. Not far below the surface was the view that any unionist was an English imperialist, a Tory, and un-Scottish.

Corbyn posed as a twinkly social democrat, while many of his supporters regarded Labour people who didn’t agree with them as Tory stooges. Worse, they tended to imagine that the world is controlled by a malign elite, and that in turn led to a blind spot about prejudice against Jews.

What a relief to leave such politics behind. In this, Keir Starmer may be like Joe Biden; the embodiment of a calmer, more inclusive politics. Biden defeated Donald Trump because enough American voters were tired of the divisiveness and the shoutiness.

As a politician from a land before time, Biden was able to keep his distance from the polarising tendencies of parts of his own party, which was becoming strident about defunding the police and whatever else, and he has continued to confuse the Republicans ever since. He is such a unifier in a nation that thinks of itself as close to civil war that some Republicans even applauded during his State of the Union speech this month.

Meanwhile, on the other side of British politics, Rishi Sunak has brought the soothing balm of competence to a Conservative Party briefly captured by a different kind of fundamentalism. Is it not refreshing that British politics has shed the absolutists – Liz Truss, Corbyn and Sturgeon – each of them preaching their exclusive truths and dividing the world into believers and non-believers?

Could this be the week that UK politics finally returned to an even keel, with a new realism in Scotland, the Tory party back from its wilder adventures with Boris Johnson and Truss, and a Labour Party having turned its back, finally and definitively, on the toxic extremism of the recent past?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks