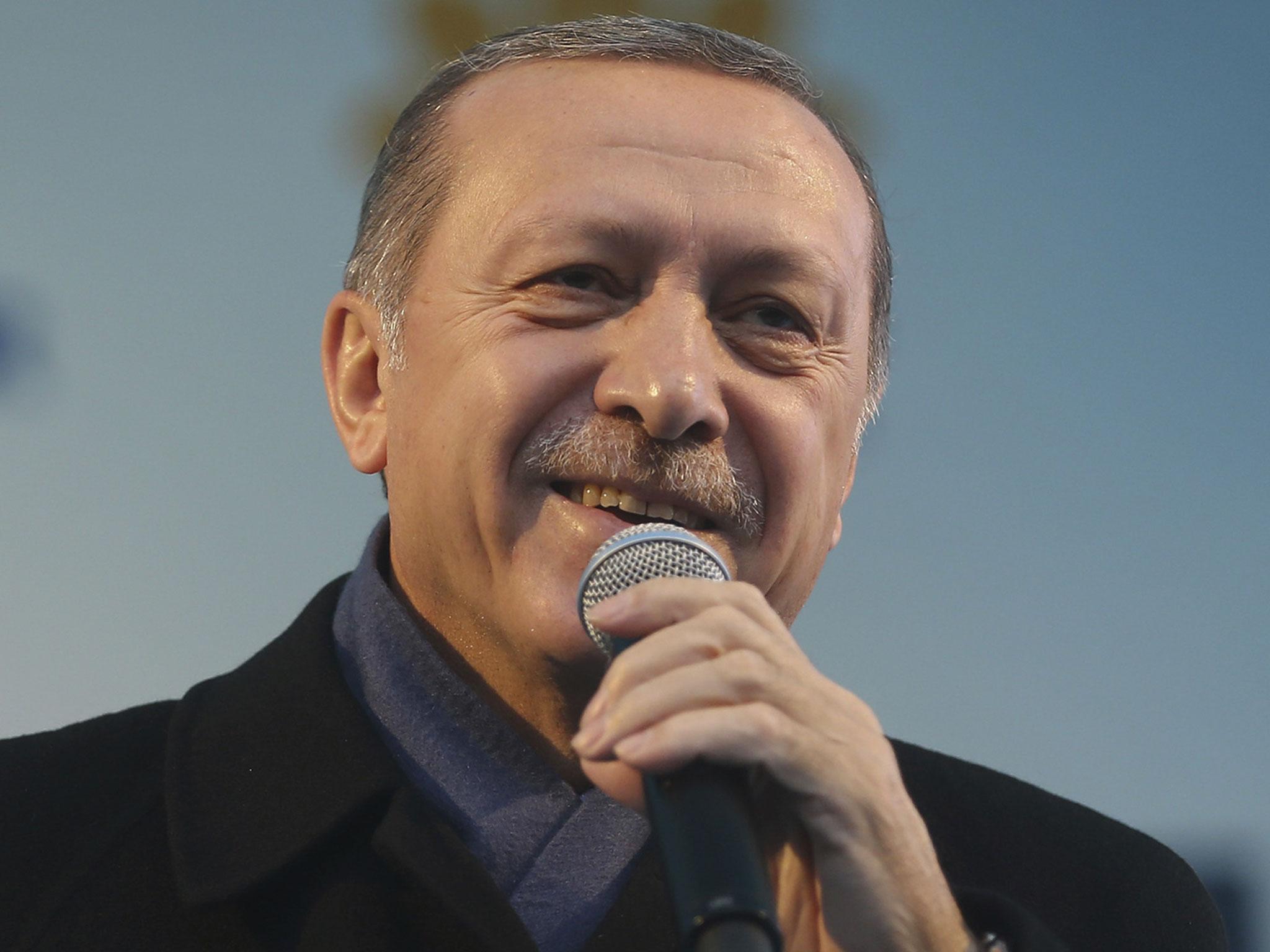

President Erdogan's falling out with the Dutch Government suits everyone politically

For the Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, the chance to take a stand against Erdogan’s plans could barely come at a better time

In politics, timing is everything. Take for instance the current diplomatic row between Turkey and the Netherlands. In many other circumstances, a speech by a foreign official to a minority group encouraging engagement back in their “home” country might have passed without fuss. But in a situation where both nations have upcoming public votes in which national identity and strong leadership are key debating points, it pays to look tough.

The specific cause of the disagreement is Turkey’s upcoming referendum in which President Erdogan is seeking to expand his executive powers. The package of measures to be voted on include the abolition of the post of prime minister and an extension of the period a president can be in office. If Erdogan wins the referendum, he could be in power till 2029. It’s no surprise then that he should want to garner support among Turks living abroad who have the right to vote in next month’s poll.

Erdogan’s ministers had planned to address rallies to the Turkish diaspora across Europe. But those intentions were rebuffed, first by the authorities in Austria and Germany, then by the Netherlands – in part over fears that the rallies would stoke tension between Turks and Kurds living in the West. Erdogan’s response, to brand both the German and Dutch people as Nazis, was at once explosive and utterly calculated, provoking a showdown and demonstrating himself to his public as a strongman fighting for the rights of Turks beyond the nation’s borders.

For the Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, the chance to take a stand against Erdogan’s plans could barely come at a better time. With a general election looming, the row has given him an opportunity both to be critical of Erdogan-style populism while at the same time spiking the guns of the nationalist Geert Wilders by seemingly limiting the rights of Holland’s Turkish minority.

Wilders for his part has sought to take advantage too, arguing that the ensuing protests by Dutch Turks on the streets of Rotterdam proves everything he has ever said about the failure of multiculturalism. In short, for both the key figures in this week’s Dutch election and for Turkey’s President, there is no political capital to be made from ending the impasse – at least, not until Thursday.

Yet putting aside the political opportunism presented by these specific circumstances, the stand-off between Turkey and the Netherlands once again shines a light on the question that has, superficially at least, come to dominate the re-emergence of popular nationalism in the last few years: immigration. Or perhaps more accurately, bearing in mind Turkey’s attitude towards its own Kurdish population, it shows the degree to which minority groups have become a political football among national leaders across the world.

Liberals condemn such discrimination. Meanwhile, many on the right argue that the current trend towards populist, nation-first policies is a consequence of the establishment/elites/left (delete as applicable) having become out of touch with the feelings and needs of the ordinary voter, especially since the economic crash of 2008. In this respect, it is no wonder that parallels have been drawn with the rise of fascism in Europe in the 1920s and 30s: and there is more to the comparison than merely the invocation of Godwin’s law.

For all that Nazi comparisons make for good headlines though, there has been much too little focus on what happened in Europe immediately after the Second World War, when numerous ethnic groups not already dispatched by Hitler’s forces found themselves – more or less forcibly – removed from their ancient homelands by free-again national governments (with the collusion of the US, Great Britain and the Soviet Union). Poles were expelled from Ukraine in their hundreds of thousands, while Ukrainians and Belarusians were thrown out of Poland; perhaps 11 million German speakers who had lived in “foreign” lands for generations were transported from areas of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania and elsewhere; and of course many Jews who had survived the Holocaust fled central and Eastern Europe altogether when it became clear that anti-Semitism was not confined to the Nazis alone.

The outcome of this post-war settlement – imposed in the end not by those who began the conflict but broadly by those who fought against fascism – was, paradoxically, a much more “nationalised” Europe than had existed before 1939. Even the EU, regarded by its critics as an exercise in supranational government, is underscored by the separate identities of its component members, each of which has committed voluntarily to, for instance, freedom of movement. But that in itself defines the shifting of populations as something unusual and official – when for centuries it happened organically throughout the continent.

Similarly, the arrival in the last fifty years of many minority groups from beyond the EU – Turks into Germany, or Algerians in France for instance – was a consequence of deliberate decisions by national governments (not the European Commission), usually in response to economic need.

The revival of nationalism in Europe today is often placed in a narrative that regards the nationalist policies of the Nazis et al as grim failures, and the post-war years as a positive experiment in pan-continental cohesion. In fact, the forced movement of people (officially sanctioned and otherwise) after World War II arguably did as much to rewrite Europe’s ethnic boundaries as anything the Nazis had done during six years of occupation – and created the conditions in which, in later years, the arrival of new minorities would eventually lead to the tension we are seeing now.

It may not be what President Erdogan had in mind when he talked of “Nazi remnants” in Europe, but perhaps we haven’t realised the half of it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies