Our prison system is at breaking point – that's why we need to put fewer people in jail

As for young offenders institutions: prison is no place for a child – they must be shut down

Imagine buying a new car, getting into the driver’s seat and starting the engine, only to find that every warning light on the dashboard is flashing. That must have been how the new Secretary of State for Justice, David Lidington, felt when he read today’s annual report by Peter Clarke, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Prisons.

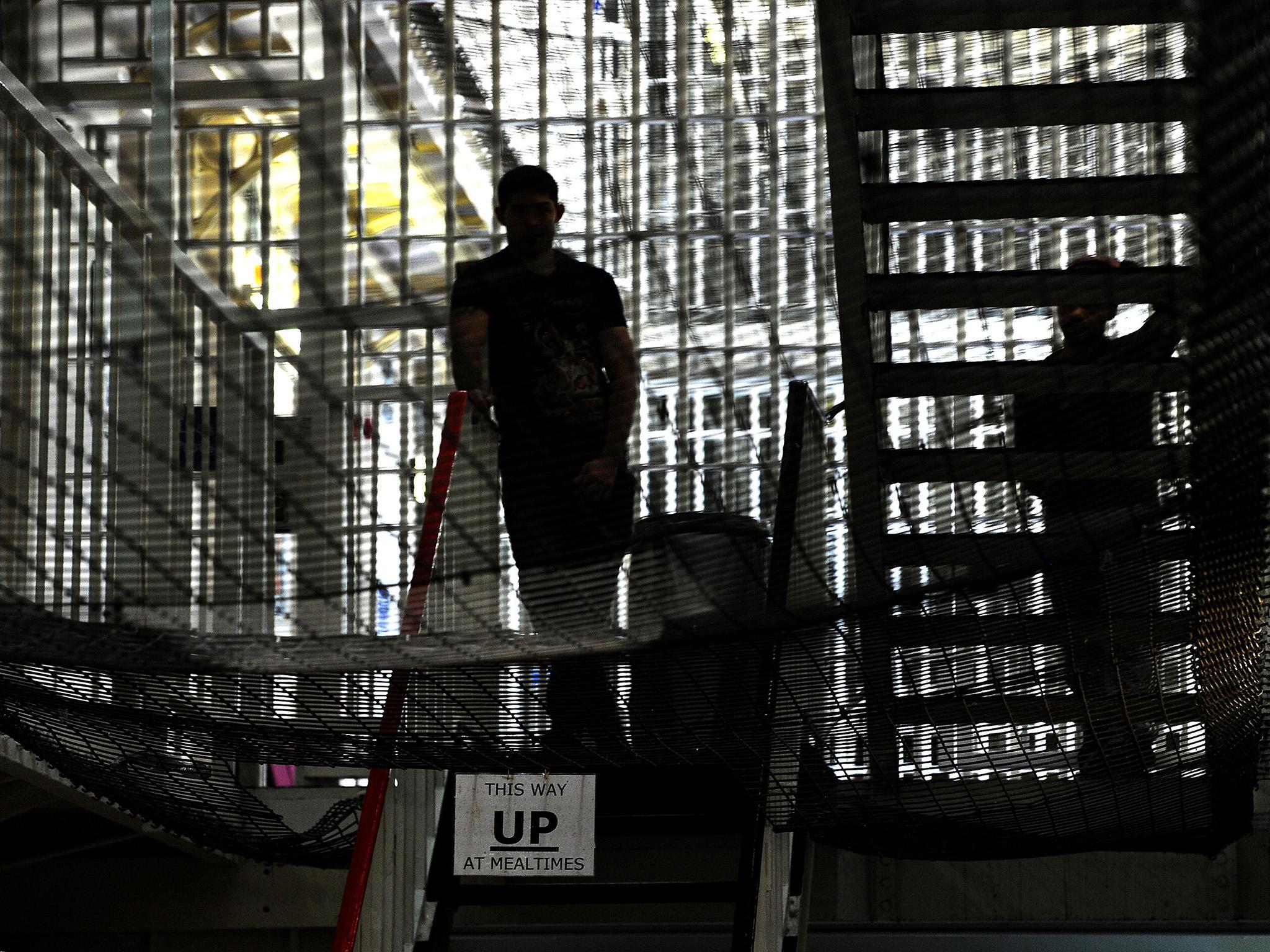

Prisons are out of control, and the statistics speak for themselves. A prisoner dies by suicide every three days in England and Wales – the highest rate since current recording practices began almost 40 years ago. Violence is rife and has reached the point where men are too scared to leave their cells. Self-injury has also risen to a record high, with women disproportionately likely to harm themselves during their time in custody. Drugs are everywhere. Conditions are so dangerous that staff fear for their lives.

The Howard League for Penal Reform has been campaigning for change in prisons for more than 150 years. Peter Clarke’s report is one of the most damning we have seen from a Chief Inspector in recent times.

“Far too often,” he writes, “I have seen men sharing a cell in which they are locked up for as much as 23 hours a day, in which they are required to eat all their meals, and in which there is an unscreened lavatory ... I am frequently shown evidence of repeated self-harm, and in every prison I find far too many prisoners suffering from varying degrees of learning disability or mental impairment.

“I have personally witnessed violence between prisoners, and seen both the physical and psychologically traumatic impact that serious violence has had on staff. My anecdotal experience is no substitute for the broader evidence-based findings, but if I have experienced this during the course of inspections, what must be the impact on the prisoners and staff who endure these things every day of their lives?”

The Chief Inspector’s strongest criticism is reserved for prisons holding children. His team has found jails where boys take every meal alone in their cells, where they are locked up for excessive amounts of time, where they do not get enough exercise, education or training, and where the cycle of violence appears to be never-ending.

“By February 2017,” he writes, “we concluded that there was not a single establishment that we inspected in England and Wales in which it was safe to hold children and young people.” This chimes with what the Howard League has been saying for years – prison is no place for a child.

So where did it all go wrong? And how could David Lidington, still only five weeks into the role, start to put things right?

Children in prison are disproportionately likely to have been exposed to chaos, neglect and abuse. We are very good at blaming children for what adults have done to them, and prisons for children are the most extreme example of that approach. They should be closed.

When we come to addressing the problems in adult prisons, we need to talk about numbers.

The prison population in England and Wales has doubled since the mid-1990s, from slightly more than 40,000 to its current mark at just below 86,000. We lock up more people than any other state in western Europe, with an incarceration rate twice as high as Germany. Before President Erdogan’s crackdown following an attempted coup in Turkey last year, there were more prisoners serving indeterminate sentences in England and Wales than in all the other Council of Europe countries put together.

As the prison population has grown, so overcrowding has got worse. Last week, the Ministry of Justice published figures showing that Swansea has the most overcrowded jail in the country, as it is designed to accommodate 268 men but actually holds 469. The situation is also severe in Wandsworth, where 1,603 men are crammed into a jail designed for 943, and Leeds, where there are 1,128 men but room for only 669.

To understand why trouble has flared in prisons so dramatically in recent years, we must consider a third set of numbers – staffing levels. Howard League research has shown how the number of officers in some jails was cut by up to 40 per cent as prison budgets shrank. With fewer staff available to unlock cell doors and escort prisoners to work, education, training and exercise, prisons have gone into lockdown. This is why the Chief Inspector has found so many people languishing in cells for up to 23 hours each day.

It should surprise no one that such conditions fuel violence. Deprived of purposeful activity, prisoners desperately look for other ways to make the time go by faster. It is surely no coincidence that drug use has escalated, and where there are drugs there is debt, and where there is debt there is bullying and violence.

We cannot build our way out of this mess. Building more jails only causes problems to grow; it does not solve them. And the idea of building new prisons to replace old ones does not work either. History has shown us that by the time you have built the new one, the prison population has grown at such a rate that you can no longer afford to close the old one.

The right way, indeed the only way, to tackle the problem is to reduce the number of people in prison. By taking sensible steps to bring down numbers, we can save lives and guide people away from more crime and despair.

But that work must start now. The prison system has been overheating for years. How long do we have until the engine blows?

Andrew Neilson is director of campaigns at the Howard League for Penal Reform

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks