So you think you've got consumer incentives in the bag? Think again

When chancellors add pennies on to the price of tobacco or alcohol at Budget time, we don’t see big falls in the public’s consumption of such items

It’s always horrible when people lose their jobs. But, sometimes, the hard truth is that redundancies can represent a victory for public policy. A plastic bag manufacturer in Lancashire last week went bust, at a cost of 40 local jobs. A manager for Nelson Packaging blamed the 5p levy on plastic bags, introduced by the Government in England last October.

That is exactly the sort of thing ministers and environmental campaigners, if they were honest about it, wanted to happen. Discouraging demand leads to less supply. And that has to mean, indirectly, fewer people employed to make plastic bags.

Yet what’s rather curious from an economic perspective is just how sensitive demand for plastic bags has been to this levy. Or, to use the economic jargon, how “price elastic” it has proved.

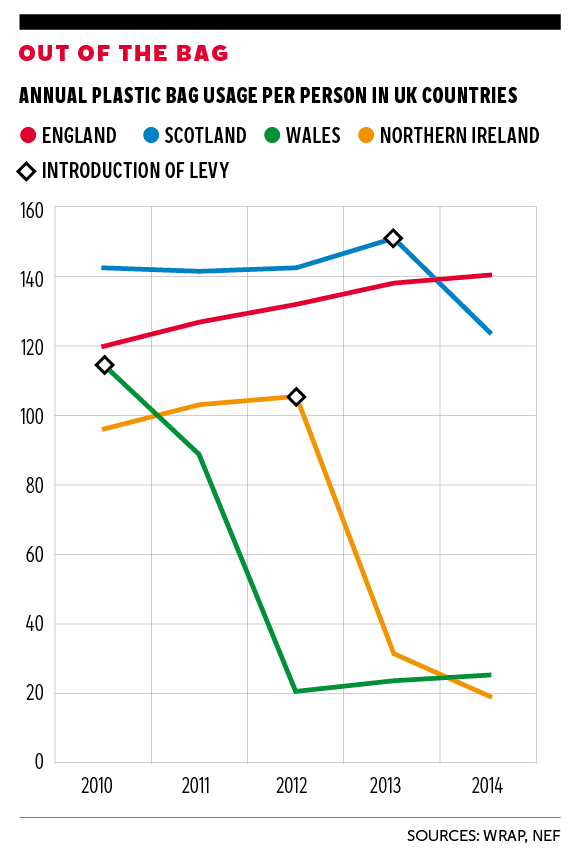

When chancellors add pennies on to the price of tobacco or alcohol at Budget time, we don’t see big falls in the public’s consumption of such items. Yet Tesco has said the use of plastic bags by its shoppers is down by as much as 80 per cent since the 5p charge was introduced only five months ago. That’s very much in line with similar falls in bag usage in Northern Ireland and Wales when they introduced similar levies a few years ago.

Consider how often you go grocery shopping. Let’s say that’s once a week and let’s imagine you do a big family shop requiring eight new bags. So that comes to 40p. Imagine you never reuse them. That’s a cost of around £20 a year. Every penny counts, particularly to families who are barely getting by.

However, that’s still not a lot of money in the scheme of things.

Many people lose up to £200 a year by failing to switch to different bank with lower overdraft charges. Similar sums are lost by people who stick with the same energy supplier. It’s likely some of the people who have changed their behaviour over the plastic bag tax have not moved to change bank or energy supplier, despite the potential saving being more than 10 times greater. It’s likely that many of the people who have stopped taking new plastic bags would not stoop down to pick up a 5p piece left lying in the street.

“Damn, I forgot to bring the bags,” my wife will sometimes cry out when we reach the checkout and face the prospect of asking the assistant to pull some new plastic carriers out of a drawer for us. But she knows that the cost of those new bags isn’t really going to make a difference to our overall household finances.

So what’s going on? Psychologists have identified a “zero price effect”. When an item moves from free (zero) to 5p, it can be more noticeable than when, for example, the price increases from 40p and 45p - even though the absolute change is identical. The 5p levy might be small but it looms large in our minds.

That’s probably something to do with it. But there’s something else too. Plastic bag use in the UK fell sharply between 2006 and 2009, with single-use bags falling from around 12 billion to 7 billion. This was largely thanks to a surge in public awareness of the environmental damage a result of various media reports and campaigns. That suggests an underlying desire among a significant proportion of the public to use fewer of them.

But usage bounced back up to 8.5 billion after 2009. It has apparently taken the 5p levy to break the dam of inaction and prompt a big shift in collective behaviour.

The 5p may not be financially significant, but it’s a regular prompt or nudge for people that wasn’t there before. The mechanics are important. People have to make a choice: do we ask for a bag, or not?

Would big signs above checkout counters urging customers to reuse bags (or to take out cloth ones) have had the same effect? It’s hard to imagine so. There is probably an element of herding and even stigma too. If everyone is reusing bags, there is a social pressure to do the same. Do you really want to be the single environmental vandal in the shop?

There’s another sense in which this isn’t only about the money. Supermarkets could technically keep the proceeds of the levy and use them to pad out their profits. But, under pressure from the Government and shoppers, they have instead pledged to give the cash raised to environmental charities. So this might be best viewed as collective social endeavour to minimise the overall use of plastic bags. That’s what those who deprecated the levy as an outrageous act of the “nanny state” – or another rapacious stealth tax imposed on a long-suffering population – missed. It’s actually pushing at an open door. This is taxation by consent.

It is well established that price changes do influence consumer behaviour. When the previous Labour government temporarily cut the rate of VAT from 17.5 per cent to 15 per cent during the 2008 recession, researchers predicted a substantive increase in aggregate consumer spending, relative to where it would otherwise have been.

Yet there can be much more to human behaviour than robotic responses to price signals. Money might even have the opposite effects to what one might have imagined. Consider blood donations. Some evidence suggests that moving to a system of paying people to give donations would result in the overall numbers coming forward falling. The act of giving blood is viewed by many as altruistic and civic, something removed from the market. Turning it into a financial transaction for personal profit could mean these altruistic donors lose interest.

A sense of fairness also matters. There is a social science experiment called the ultimatum game in which two people are gifted a small pot of money. One person is then allowed to propose how to split the windfall. If the second person accepts the split, it is distributed as proposed. But if the second person rejects the proposal, neither gets anything. Logically, the second person should accept any split that means receiving a payment above zero. It’s surely better to get something, rather than nothing, even if the other guy gets more. But in reality, anything significantly different from a proposed straight 50-50 split of the windfall tends to be rejected. People would apparently rather get nothing than feel insulted or exploited.

Financial incentives are powerful influences on our behaviour. But, as the curiously powerful plastic bag charge vividly demonstrates, they are by no means the whole story.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies