Widening inequality is largely a US and UK phenomenon – why?

The housing market no longer acts as an escalator when growing numbers cannot get on it, and there is a strong correlation between educational attainment and the educational attainment of the next generation

In modern Britain, there is something stirring around the idea of inequality: something new and worrying. This is based on the observation that inequalities of income, wealth and opportunity between classes, regions and generations are worsening, and that Britain is becoming a more unequal society compared with its neighbours and its past. This inequality is not merely offensive to the sensibilities of progressive minded folk, but is doing serious damage to wider society and our economy.

Sometimes an event crystallises such feelings. The Grenfell Tower disaster wasn’t just a horrific accident with severe loss of life, but illustrated graphically how the less well-off are not listened to by those with authority. Close by geographically, but light years away socially and economically, live London’s super-rich.

What motivates me is the way this new Britain contrasts with the more egalitarian society in which I grew up. In 20 years, my parents progressed from being factory workers in a house with an outside loo to being part of the professional class and living in a detached house. Though they both left school at 15, they saw me grow up to attend an “elite” university.

My sense today is that big differences in living standards and opportunities have opened up. While it is possible to argue about definitions of inequality, some trends are indisputable.

First, earnings of the top 10 per cent of full-time workers doubled between 1978 and 2008, whereas those of the median grew by 60 per cent and the bottom 10 per cent by just a quarter. After the financial crisis, overall earnings fell substantially over the next five years before recovering slightly, but they are falling once again. This combination of absolute decline following generations of widening inequality explains much of the current sense of unfairness.

Second, the standard measure of income inequality, the Gini coefficient, shows Britain’s post-tax inequality rising strongly in the 1980s (from 28 per cent in 1978 to 41 per cent in 1990) though it has stabilised a little since (to around 37 per cent). Having once been one of the more egalitarian developed countries, the UK is now one of the least. Third, there has been an extraordinary concentration of rewards in the hands of the top 1 per cent, and within that group, the top 0.10 per cent.

Finally, wealth inequality is greater than for incomes and is growing. In the absence of compensating wealth taxation, high earners can turn their income into assets, and the value of assets can be compounded through investment. This is then passed on as inheritance, entrenching inequality across time between generations and classes.

This has had dramatic effects on social mobility. My parents’ experience of economic and social mobility would be difficult to achieve today. The housing market no longer acts as an escalator when growing numbers cannot get on it, and there is a strong correlation between educational attainment and the educational attainment of the next generation. The argument that we shouldn’t worry too much about inequality because we have compensating social mobility is no longer true, if it ever was.

The one serious argument put up in support of inequality is that it is a necessary evil: a concomitant of a dynamic, capitalist economy in which there must be incentives to innovate, invest, save and work. Yet there is no obvious explanation as to why the top 1 per cent, and especially the top 0.1 per cent, have accelerated away, since Western economic performance has deteriorated in the past decade. This widening inequality (with indifferent economic performance) is largely a US-UK phenomenon, with nothing like the same story in Germany, Scandinavia or Canada.

Indeed, there is abundant cross-country evidence that too much inequality can harm economic performance, and that redistributive politics can do good. Studies suggest that higher levels of inequality are associated with unproductive rent-seeking; contribute to financial instability; feed asset bubbles rather than productive investment; weaken demand and encourage high levels of household debt; and lead to underinvestment in education and health.

The clear conclusion is that inequality should no longer be seen as the preserve of idealists and socialists. Too much inequality is bad for all of us. Growing inequality is linked to poor economic performance, greater instability and unhappiness. There should be support for measures which reduce inequality and reduce economic and social ills.

Progressive income tax is often seen as the politically appealing route to greater equality. The left – as Labour’s manifesto demonstrated – remains attracted to high marginal tax rates on the rich. Yet history shows this is counterproductive, leading to diminishing returns. There is greater merit in trying to eliminate the large opportunities which exist for legal tax avoidance and arbitrage, and encouraging greater public disclosure of tax returns.

Wealth inequality is the accentuation and entrenchment of existing income inequality, through returns generated on assets and the passing down of inheritance. So, if we are serious about tackling inequality, we must tax wealth effectively through a wealth tax or combination of wealth taxes.

A first step would be to reform council tax – regressive and based on outdated property values – by creating more bands and making the bands proportional to property the value.

This would need to be combined with effective taxation of inherited wealth. Inheritance is a major factor perpetuating inequality and inhibiting social mobility. That is why genuine meritocrats – like Bill Gates – argue for aggressive taxation of inheritance. Yet UK policy has moved in the opposite direction.

Wealth taxation is not anti-business. Well-designed wealth taxes encourage long-term investment and entrepreneurship, while discouraging speculation, inheritance and passive asset ownership. Entrepreneur Luke Johnson argues for taxing property more and income less.

Tackling inequality of wealth, particularly property, is uncomfortable in a country where property ownership has almost religious significance. But the means are there. Ignoring the problem will only empower extremists.

I want to lead on the issue of reducing inequality. The Institute for Fiscal Studies judged the 2017 Lib Dem manifesto the most redistributive of all. There is a coalition legacy of measures like the pupil premium, improving minimum-wage enforcement, regulating executive pay and seeking to lift low earners out of tax. This will be a theme of my leadership.

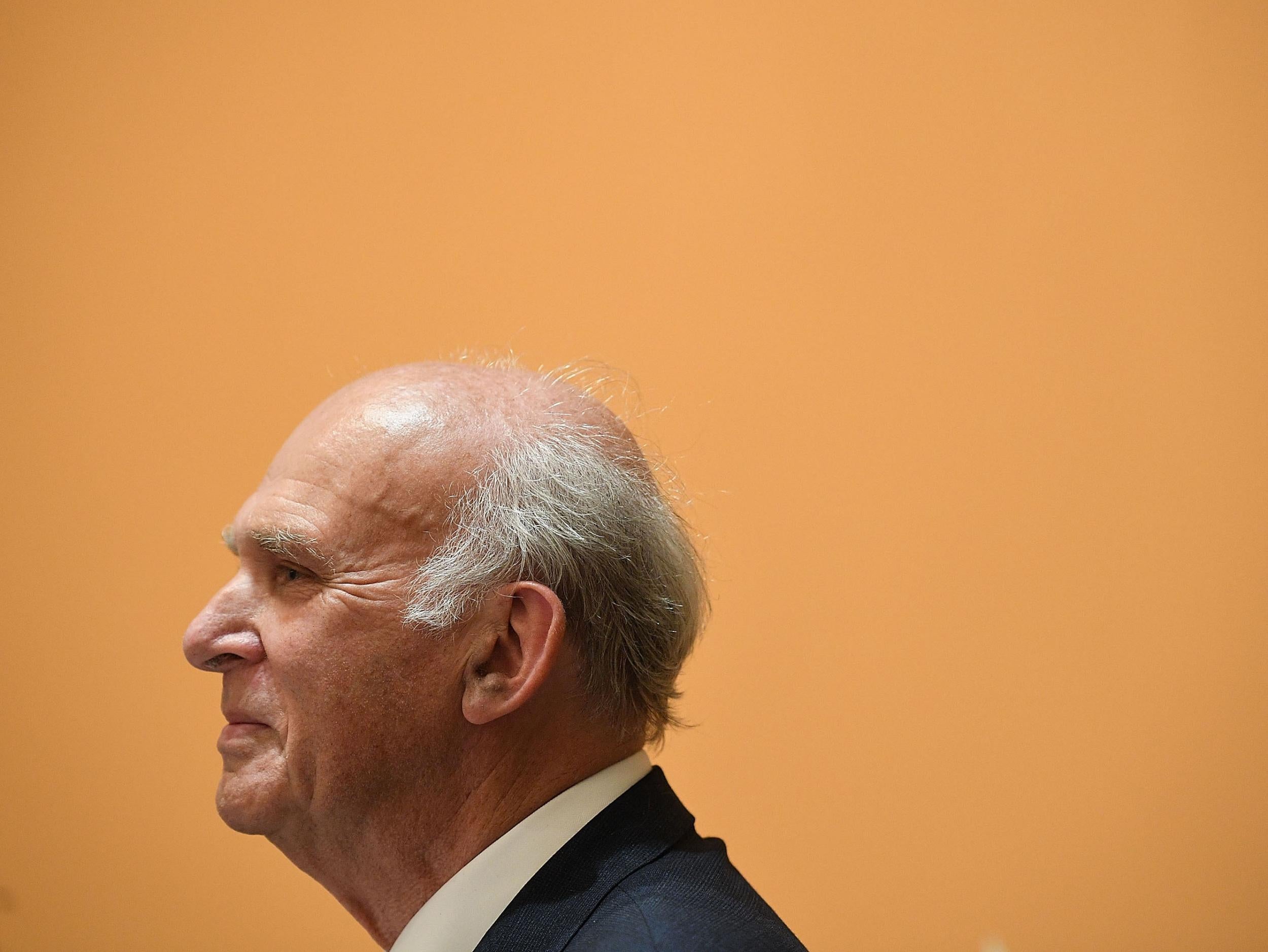

Sir Vince Cable is leader of the Liberal Democrats and MP for Twickenham

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies