The Windrush statue is offensive – no wonder people are boycotting it

It’s bizarre, at best, that the government has sponsored this monument while continuing to deny the existence of institutional racism

The Windrush pioneers helped to build Britain, and it isn’t a bad thing that a permanent tribute to them – if that’s truly what it is – has been installed in one of the country’s busiest railway stations.

However, given that thousands of people affected by the Windrush scandal have yet to receive compensation from the Home Office for their plight, the response has understandably been mixed. Official figures show that fewer than half of the scheme’s applicants have received a final decision, so it’s not as though the Windrush community can exactly rejoice. Justice delayed is justice denied.

The scheme has been fraught with unacceptable delays, needless complications, and unreasonable requests for evidence. I have previously reported that applicants were being told they must prove their case “beyond reasonable doubt” before receiving payments. More often than not, these victims have been treated as criminals, not people who are utterly deserving of restitution.

Naturally, criticism has abounded of the apparent inability of the Home Office to prioritise the dispensation of justice, with campaigners, commentators, public figures and politicians all highlighting the painfully obvious fact that the department is failing victims of the Windrush scandal, yet again.

There are continuing calls for the compensation scheme to be taken out of Priti Patel’s Home Office and transferred to an independent organisation, in order to increase trust while encouraging more applications.

All of this has been bubbling away in the background as the UK observes its fourth national Windrush Day, so you can understand why not everyone’s in a celebratory mood – particularly when one considers the impact on Black and brown communities of recent Home Office policy, from the Rwanda migrant plan to the Nationality and Borders Bill.

Moreover, some members of the Windrush community are scoffing at the government’s grand monument to the trailblazing Caribbean migrants. At a cost of £1m, and paid for by the government, the statue is said by some to have been funded with “blood money”.

Though it is being touted by ministers as a tribute to the “dreams, ambition, courage and resilience” of the Windrush generation, sadly their hopes and vitality have too often been crushed by the weight of oppression dispensed by successive governments of this country – something that has been conveniently glossed over.

It seems bizarre, at best, that the government has sponsored this monument while continuing to deny the existence of institutional racism and the impact it has on people such as those from the Windrush generation, as well as their descendants.

From what I’m hearing, it seems that not many members of grassroots communities were actually invited to the grand unveiling. Some have expressed fears that it was an occasion restricted almost exclusively to the “great and the good”. The word on the street is that the majority of those invited to attend were people with fine titles and an assortment of letters after their names. Why is that?

Only selected journalists were invited, too, which raises worrying questions about access and the function of our free press. I was invited a few weeks ago by the government to put my name forward for the unveiling, and then promptly told I couldn’t attend after all – after Prince William’s attendance was confirmed – because of “restricted numbers”.

I can’t help but consider how refreshing it would have been if more Black journalists – working in an industry that is still not anywhere near as diverse as it should be – had been permitted to attend an event dedicated to pioneering Black migrants. Particularly Windrush descendants like myself. And perhaps how different, balanced, and truly evaluative the coverage around the monument could have been, too.

When members of the royal family attend events, the Buckingham Palace press office usually handles media accreditation, and it is highly selective. The Voice got a look in, as a specialist national African-Caribbean media platform (shout out to my former employer) – we can understand how terrible it would otherwise have looked.

The “rota” – the name of a small group of journalists permitted to cover royal events – typically choose (between themselves and the palace) which journalist covers which event, taking it in turns. So they get first (and typically only) dibs at reporting first hand on functions attended by royals. That’s how it’s been for decades: if you’re not in the rota, then it’s curtains for you.

With all of this said, I want to make it clear that my side-eyeing of this unceremonious snub is not about ego at all. It’s about the principle, and a fundamental concern for the state of Fleet Street when Black journalists (plural) aren’t able to cover events about Black people, that happen also to be attended by nobility. After all, our principal obligation is to hold power to account, as opposed to fawning over it to prop up the status quo. I know that other Black journalists who were not given access feel the same way.

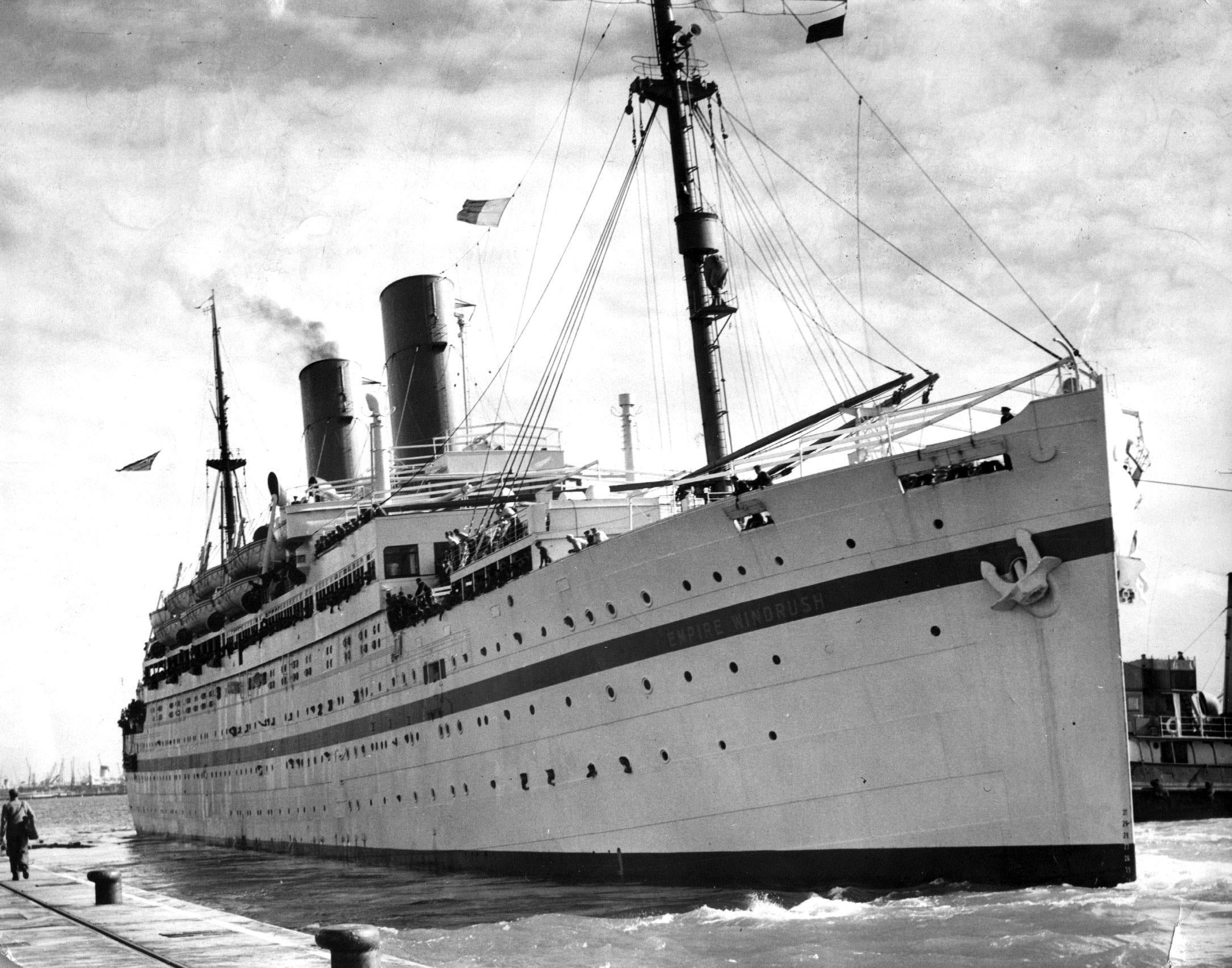

There are members of the Windrush community who are deeply unhappy with the statue’s location, given that the Caribbean men and women who arrived on the Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks in Essex, on 22 June 1948, did not travel from Waterloo station to Brixton, where many of them spent their first night.

On that note, teacher Samuel Nelson asked, during an interview with The Independent published earlier today: “Where was the campaign to inform and involve people about it – the rigorous consultation?”

Arthur Torrington, co-founder of the Windrush Foundation charity, has strongly opposed the government’s plans to erect a monument at Waterloo since it was announced by former prime minister Theresa May three years ago.

At the time, he accused the government of behaving “arrogantly” and “treating the Caribbean community like children” by not consulting with key groups. This dismissive and callous attitude, he argued, is what led to the Windrush scandal in the first place. Torrington also suggested that the monument be placed in Brixton instead.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

No matter the endeavour, it’s not always possible to please everyone. However, the various concerns around the Windrush monument are valid, and there’s little indication that fears about the government’s overall failure of – and disengagement with – Black communities will be addressed any time soon.

In the meantime, some of us have opted to nod politely at the Windrush monument, which was created by our very own Jamaican sculptor Basil Watson, to whom respect is due, as a commendable gesture to our forebearers.

Others told me they were planning to boycott the unveiling of it altogether, despite the involvement of well-intended and beloved members of our community such as the right honourable Floella Benjamin, and had planned a day out instead.

Personally? On Windrush Day, I will be busying myself with alternative ways of celebrating the efforts of our early pioneers. I pay homage to them each day, anyway, as walking testament – a witness to their heart and perseverance.

All of my grandparents, and my father, moved here and made this country what it is. Many of us live in hope that the victims, and survivors, of the Windrush scandal will be indemnified.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks