The Duke of Richmond on reinventing Goodwood and making it into the ‘Woodstock’ of its day

The founder of Goodwood Festival of Speed and Goodwood Revival might be best known for heritage motor shows, but his first love has always been photography. He sits down with Helen Coffey to talk life behind the lens, working with Stanley Kubrick and using art as a force for social good

It’s alchemy, you know – it’s a magical thing…” Charles March, the Duke of Richmond, is talking about his first love with a respect bordering on reverence. He’s best known for putting British motor racing back on the map by launching the hugely popular annual Goodwood Festival of Speed and Goodwood Revival events. But something else stole his heart long before his name became synonymous with heritage cars: photography.

The duke “hated school, pretty much” and left at 16 to pursue the only thing that had ever made sense to him. “Taking a picture is a magical process, especially in the old days,” he tells me, misty-eyed from the family seat of Goodwood Estate in Sussex. “You had your film, you developed your film, and in the dark you’d see this wonderful thing appearing in front of you. And you’d just hope you’d got it right.”

There’s an appealing romanticism about this vision of photography as it was, before digitisation: a miraculous chemical reaction turning light into printed image. Though the modern era has robbed us of much of this sorcery, the duke’s enthusiasm for the medium remains undimmed. At the age of 70, he is showing his latest exhibition, entitled Sandscript, at Hamiltons Gallery in London until 16 January 2026 (more on that later).

It probably didn’t hurt that his introduction to the industry was the stuff of legend; at the tender age of 17, Charles landed a gig shooting stills for Stanley Kubrick. The year he spent working on the filmmaker’s 1975 historical drama Barry Lyndon was, unsurprisingly, transformative. “It was an amazing experience at that age, to be around people for whom there’s no compromise,” the duke explains. “It just had to be perfect. That taught me a hell of a lot.”

From there, he travelled solo around Africa for a year, taking pictures in Tanzania, Somalia and Ethiopia, before returning to London to work on editorial shoots for glossy magazines including Tatler, Harper’s Bazaar and Italian Vogue. A twist of fate gave him another pretty cool claim to fame: the duke was the photographer for the first ever London fashion collections in 1975. Orchestrated by the designer, artist and doyen of fashion PR Percy Savage, this was the forerunner of London Fashion Week. “I took thousands of catwalk pictures,” Charles recalls fondly. “It was good fun.”

Next came major, big-budget advertising campaigns for brands like Benson & Hedges and Levi’s. Forget the 1960s Manhattan of Mad Men – London in the Eighties was the place to be if you wanted to make it in the ad business. “The advertising world was on fire,” the duke tells me of that time. “London was the best place in the world, the agencies were the best in the world, the creative demands were the best in the world. It was all about winning awards and doing great work – and we weren’t worried too much about the client.”

This was a time before Photoshop, a time when any trickery had to be done physically in the studio, using intricate model-making, set design and camera angles. The shoots used to take weeks. One campaign Charles shot for a fabric collection by the British design company Osborne and Little, entitled Shadows, was iconic enough to be selected for the Pompidou Centre’s permanent exhibition One Hundred Images of Advertising Photography from 1930-1990.

The Nineties saw Charles move from London to take over the management of Goodwood Estate, a task too hefty to be compatible with maintaining a career as a full-time professional photographer – especially as the duke had designs on the property’s old racetrack. Built by his grandfather, Freddie March, it first opened in 1948. As a boy, Charles “absolutely loved it”; to his dismay, the track closed when he was around 10 years old. “I always thought it would be great, one day, to get that going again,” he says. But getting the go-ahead to reopen the track was far from straightforward.

In the interim, the duke put on the first Goodwood Festival of Speed in 1993, just to gauge how much appetite there was for a motor show and see whether the estate’s long association with cars still had any clout. It was an instant, roaring success. “The first year we were told we’d get 2,000 people – and 25,000 people burst through the doors. It was like Woodstock or something! It was crazy.” Then, after years of negotiating, Charles and his team finally got permission to reopen the racetrack and hosted the first Goodwood Revival in 1998.

In the dark you’d see this wonderful thing appearing in front of you. And you’d just hope you’d got it right

These flagship events – along with a 4,000-acre organic farm, two 18-hole golf courses, Goodwood Aerodrome and Flying School, and a hotel – have ensured that Goodwood more than washes its face, bringing in a reported annual turnover of around £100m, with profits of over £20m. It’s been something of a masterclass in invigorating a flagging estate and making it financially viable in the 21st century, a task that many other aristocrats have struggled with when faced with the exorbitant costs of maintaining the crumbling ancestral home. “I think you have to have lots going on,” the duke says thoughtfully of Goodwood’s revival, “but I think they need to be authentic things which can relate to the place and make sense.”

Even in launching the festivals, Charles’s artistic eye and previous profession behind the lens proved surprisingly useful. “I didn’t imagine it would be any help to me at all,” he says, “and then, suddenly, I found I was using the same people, lots of the model makers I’d used, to build sets and create things…”

And behind the whirlwind of transforming the estate into a profitable business, photography evolved from career to respite – a labour of love, rather than a labour for clients. Unencumbered by creative briefs, the duke started to take abstract photos. Famed art critic and curator Edward Lucie-Smith was impressed enough to offer to curate a show in Bermondsey in 2012. Entitled ‘Nature Translated’, it went, says Charles, “surprisingly well” – so much so that the Russian State Museum requested to transfer the show to St Petersburg. The Moscow Biennale followed, as did shows around the world in New York, LA and Rome. Only Covid curbed the momentum.

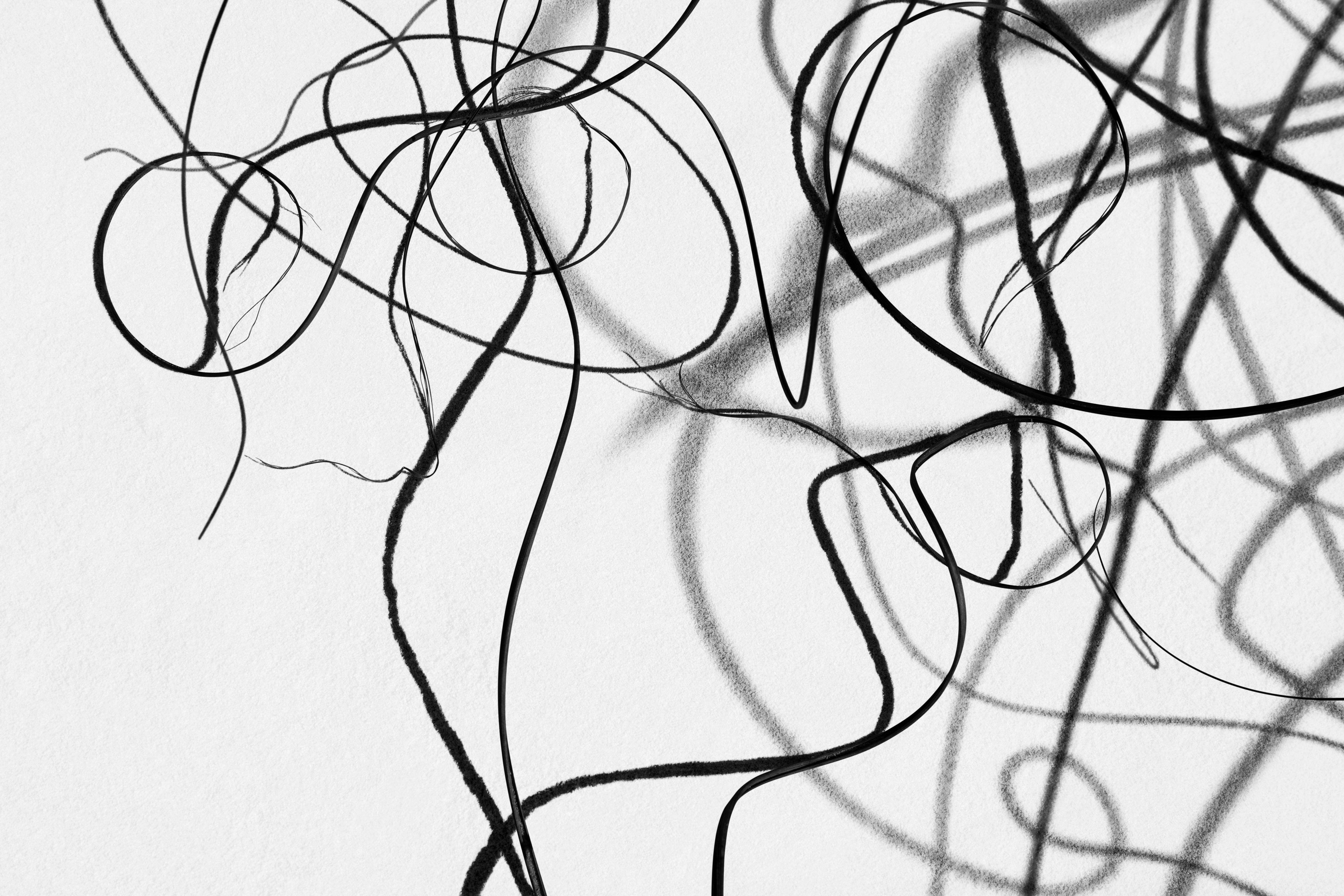

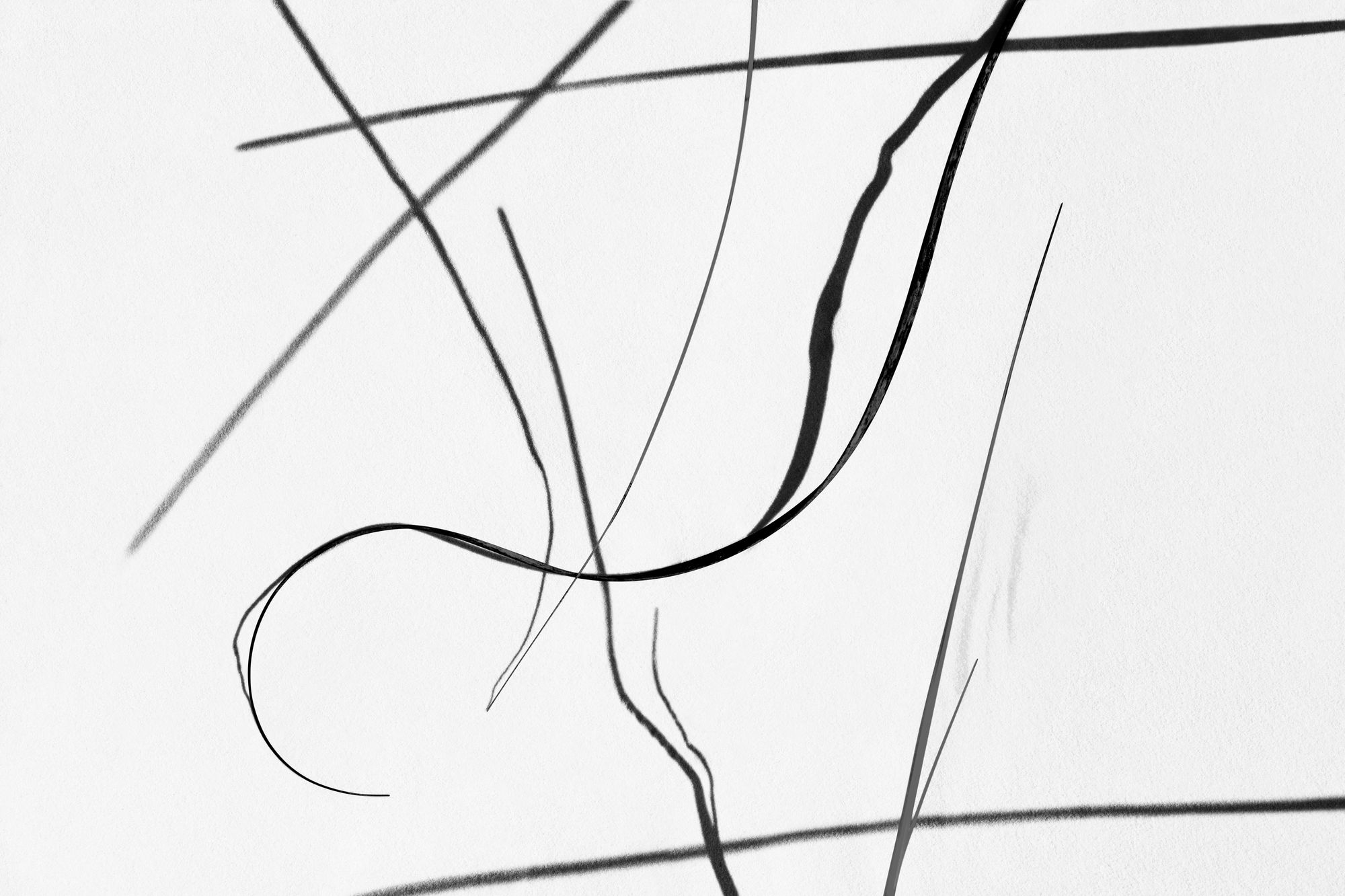

Sandscript, a series of pictures taken on the Bahamian island of Eleuthera over the course of several years, is the duke’s first exhibition since the pandemic. The images of sand, grass and twigs are far more evocative than the sum of their parts. “Everything is about to be swept away,” he says of these compositions. “It’s all there for a second, and then it’s gone. It’s heartbreaking, ephemeral; a time and space thing, I suppose.” This poetic description reflects the pieces themselves – they look more like black and white drawings scratched in ink and sketched in pencil than photos, somehow. Curling tendrils of grass form lazy loop-de-loops and undulating lines on the page; twigs form their own morse code-like language of dashes and dots.

The show will also tie in with another of the duke’s passion projects: this year he’s stepped up to chair “Generation Potential”, the 10th anniversary campaign for The King’s Trust International. The idea is to support a million young people into work over the next 10 years within the 21 Commonwealth countries in which the trust operates; Charles has pledged to raise £10m. As part of these efforts, all the money made from the Sandscript pieces will go towards the project. “We’ve just sold a very big one,” he tells me happily. “That’s got us off to a good start.”

Art and charity became even more intertwined at Goodwood this year when the estate’s Art Foundation opened in May. Featuring the work of internationally acclaimed artists set amid the natural landscape, the idea of the new not-for-profit is to foster wellbeing, creativity and lifelong learning “through engagement with art and a connectedness to nature”. There’s a particular focus on education and school visits, especially for kids who haven’t had much support in pursuing the arts: “Children who are struggling at school, maybe even excluded from school, where something like discovering their interest in art, understanding art, or someone showing interest in their abilities as young artists, can make all the difference.”

I’m not sure whether he realises it or not, but Charles could almost be describing a younger version of himself as he talks about wanting to engage this overlooked demographic. After a lifetime in which photography has remained the one true constant, he’s surely proof that it really can make “all the difference”.

The Sandscript exhibition will be displayed at Hamiltons Gallery in London until 16 January 2026. Click here to donate to the Generation Potential campaign.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks