The greatest fictional detective? A new book tells us why it’s Poirot

0Is Poirot the greatest of them all? Mark Aldridge thinks so and he reminds us all why we should too

In a recent US poll to choose the greatest fictional detectives of all time, the top four vote-getters, tallied in descending order, were Quebecois Armand Gamache, Sherlock Holmes, Harry Bosch and Hercule Poirot. “Pfui,” as American writer Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe would say.

Faced with a mind-boggling murder, would anyone turn to Louise Penny’s Gamache instead of Sherlock Holmes or to US writer Michael Connelly’s Bosch over Hercule Poirot? I certainly wouldn’t. What the poll actually reveals is the tyranny of the contemporary. The results reflect the influence of a devoted social media fan base, a continuing TV series and two best-selling authors still regularly bringing out new work.

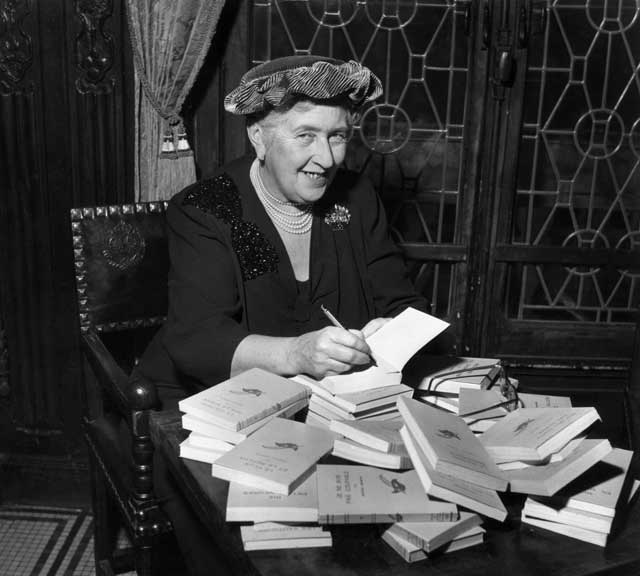

No, looked at historically, the only true contenders for world’s finest super-sleuth are Holmes and Poirot (with Wolfe and GK Chesterton’s Father Brown close behind). Being a member of the Baker Street Irregulars and having written a book about Arthur Conan Doyle, I don’t need to say more about my own loyalties. But what about that other fellow, the protagonist of 33 novels and more than 50 short stories by Dame Agatha Christie? As it happens, Mark Aldridge’s Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Greatest Detective in the World exhaustively and entertainingly surveys the book, stage, radio, magazine and film appearances of that fussy little Belgian, known for his impressive moustaches and his even more impressive “little grey cells.”

Read More:

Are family wagers an under-recognised generator of literary accomplishment? In 1916, Agatha Christie argued with her sister Madge that it must be relatively easy to write detective stories. To prove it, Christie jotted down some ideas, scribbled for three weeks in a hotel and came away with the manuscript of Hercule Poirot’s first case, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. After several rejections, the novel was finally published in 1920 when its author was 30 years old.

For the next decade, Christie experimented with various kinds of thrillers and whodunits, while creating a sensation in 1926 with The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. By the 1930s she was laughingly calling herself “a sausage-maker”, cranking out two or even three books a year. In nearly every instance, the least likely suspect, anyone with an unassailable alibi or the person with no apparent motive would turn out be the ruthless killer. Several of the Poirot mysteries from this decade are breathtaking classics of misdirection, notably Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and The ABC Murders (1935).

Aldridge’s encyclopedic book features brief, spoiler-free plot summaries, quotes apt passages from contemporary reviews and brightens nearly every page with postage-stamp-sized reproductions of dust jacket and paperback cover art, photographs or movie stills. Being a lecturer on film at Solent University as well as the author of Agatha Christie on Screen, Aldridge particularly shines in his behind-the-scenes account of the David Suchet television series and in his even-handed appraisal of Death on the Nile and Evil Under the Sun, two spare-no-expense films starring a slightly buffoonish Peter Ustinov. In a foreword, actor and screenwriter Mark Gatiss calls the second “the best time anyone can have in the cinema”. To check that assertion, I rented Evil Under the Sun and can vouch for it as a perfect Covid-era escape, the action being set on a gorgeous Mediterranean island, with a glamorous cast dressed to the nines in 1930s outfits, and everyone – especially Diana Rigg and Maggie Smith – camping it up and having a ball.

Aldridge’s bold subtitle, The Greatest Detective in the World, echoes Poirot’s self-description (in 1928’s The Mystery of the Blue Train). Though that claim is debatable, the book itself unquestionably belongs on the same shelf as John Goddard’s Agatha Christie’s Golden Age, which meticulously dissects Poirot’s novel-length investigations and John Curran’s two volumes devoted to Dame Agatha’s “secret notebooks”. However, Aldridge’s text should have been more closely copy-edited, not just to catch some minor factual errors – forthrightly listed on his website – but also to fix a number of loose and baggy sentences.

Having so enjoyed this celebration of all things Poirot and in the mood for more, I impetuously decided to try an experiment: What would it be like to reread, after half a century, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd when I already knew its trick?

This time, Christie’s hints to the killer’s identity stood out almost too obviously, yet I quickly surrendered to the zest and smoothness of the fast-paced storytelling. James Sheppard, the village doctor who assists Poirot and narrates the book, proved far more witty than I remembered, though his deductive skills are no better than Dr Watson’s. When Sheppard first sees Poirot, he tells his comically nosy sister Caroline: “There’s no doubt at all about what the man’s profession has been. He’s a retired hairdresser. Look at that moustache of his.”

Throughout, Christie excels in using conversation to propel the action (and to plant clues). However, the various people suspected of Ackroyd’s murder – the enigmatic butler, the pretty parlour maid, the blunt Major Blunt, the fair-haired ingénue, the no-good heir – are such genre stereotypes that I grew convinced that Christie employed them, here and throughout her work, in a spirit of ironic affection. She recognised how inherently artificial her mysteries were.

Consider the swirl of activity in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd before and after he is stabbed with a Tunisian dagger in his study. Each member of his household has something to hide, during one crucial hour several people frenetically run around like characters in a French farce, and everyone always knows the precise time they did anything significant. Ultimately, for Christie, the true solution needn’t be plausible, merely possible. Still, one key revelation near the end – involving a bit of period technology – struck me as unfair, being contrary to what we’d previously been told about it.

Read More:

No matter. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd remains a triumph. As Poirot stresses when speaking of its solution, “Everything is simple, if you arrange the facts methodically”. That sounds easy enough, but only a great detective, like the fastidious Belgian (or Sherlock Holmes!), can disentangle the essential from the inessential.

The Greatest Detective in the World by Mark Aldridge. HarperCollinss, £25

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks