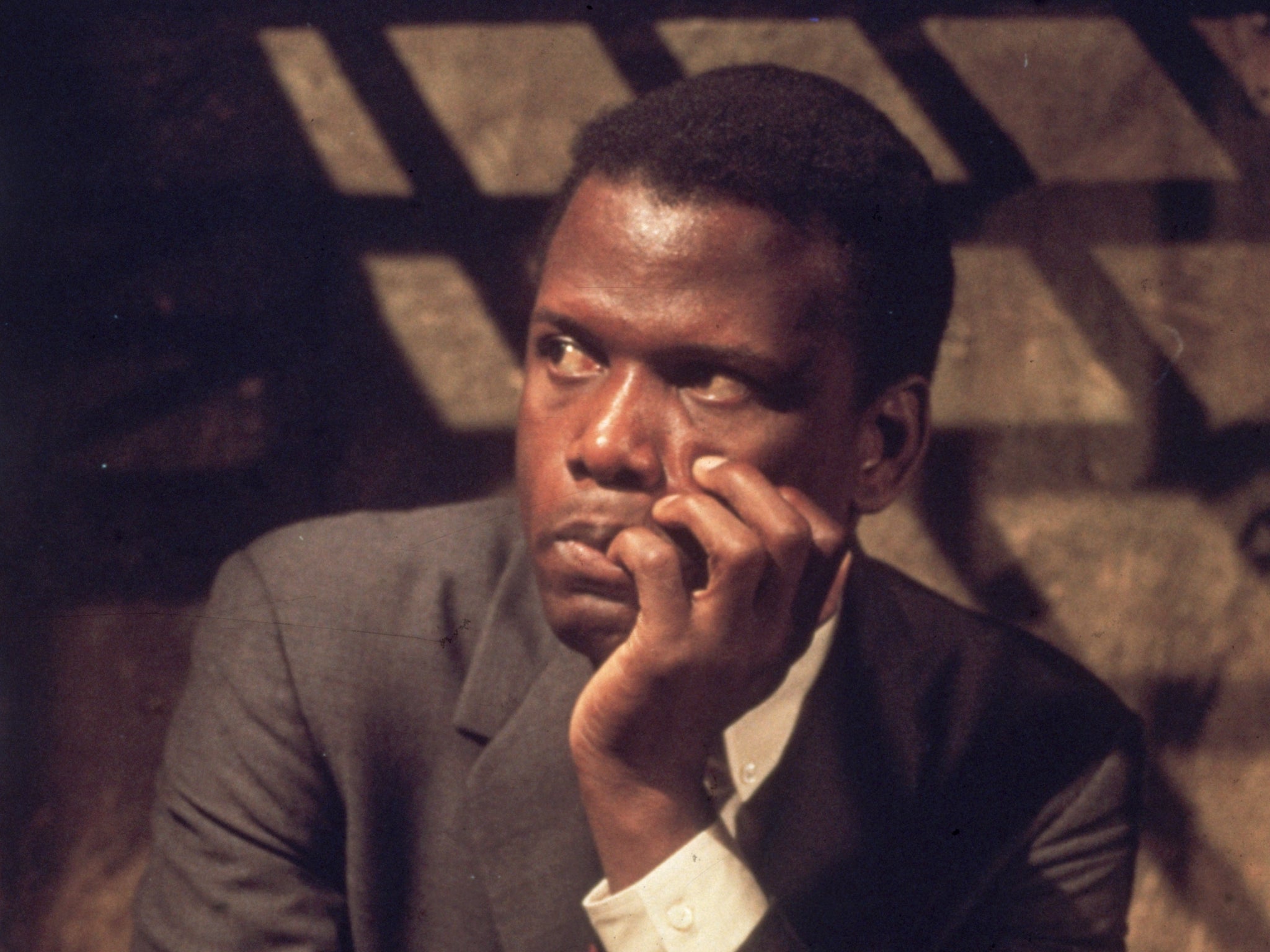

Sidney Poitier: The charming trailblazer who continually challenged stereotypes

After the Academy Award winner dies at 94, Geoffrey Macnab pays tribute to a singular actor whose profound influence and legacy will be everlasting

If you want to know what white middle-class America made of Sidney Poitier, a good place to start is with the reception the Manhattan socialites played by Stockard Channing and Donald Sutherland give to Will Smith’s con artist in the movie of hit play Six Degrees of Separation (1993). Smith plays Paul, a stranger who turns up at their door, saying that he has just been mugged and claiming he is Poitier’s son. They’re delighted by him. He is urbane, charming, well-educated... just like his dad – and seemingly possesses no threat to them. They’re only too delighted to lavish their munificence on him.

Poitier was the first black man to win the Academy Award for Best Actor, for Lilies of the Field (1963). He was the star who made white liberal types, like those played by Channing and Sutherland, purr with pleasure about his performances and feel good about themselves in the process. There is a tremendous moment in Six Degrees during which Smith delivers a rapid-fire monologue about the man he claims is his father, giving his white hosts a potted history of exactly how Poitier made it to the top. This was a rags-to-riches story of the most extreme kind.

The actor certainly came from very humble beginnings. Poitier was born prematurely in Miami in 1927, weighing only three pounds. He very nearly died at birth. His father was an impoverished farmer from the Bahamas who had come to Florida to sell tomatoes. The “future Jackie Robinson of film” grew up so poor that – as Smith puts it – “he didn’t even own dirt”. When he first arrived in New York in 1943, he lived in the most impoverished circumstances imaginable, eking out an existence as a dishwasher and teaching himself how to read by studying newspapers.

From this very unpromising start, he became one of the biggest box office draws in the US. As his biographer Aram Goudsouzian wrote about Poitier, there was a long period of his career when he was “Hollywood’s lone icon of racial enlightenment; no other black actor consistently won leading roles in major motion pictures”.

In his films, Poitier would often play protagonists who were deeply frustrated at the prejudice they faced but that frustration would always be tempered. His characters weren’t trying to overthrow a racist system but to change it from within. His image, as Goudsouzian put it, was “tied to non-violence and integration”. Director Stanley Kramer called him “the only actor I’ve ever worked with who has the range of Marlon Brando – from pathos to great power”. Poitier, however, was rarely allowed to play The Wild One-like rebels who made Brando famous or to get in touch with his inner Stanley Kowalski. Even when he was cast as a young delinquent in Richard Brooks’ Blackboard Jungle (1955), it was very telling that he was ultimately shown to be on the side of the authorities as represented by the idealistic school teacher played by Glenn Ford.

Poitier’s range, though, was enormous. He played a journalist investigating, and goading, an Ahab-like US Navy destroyer captain (Richard Widmark) in James B Harris’s The Bedford Incident (1965); he was a hipster jazz musician in Paris Blues (1961); a Moorish warrior king in Viking saga, The Long Ships (1964); a church minister in anti-apartheid drama, Cry The Beloved Country (1951); and he was Simon of Cyrene, helping Max von Sydow’s Jesus carry his cross in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965). He could do light romantic comedy (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner), social realism and action movies. He even ventured into musicals, starring, albeit reluctantly and not doing his own singing, in Otto Preminger’s screen version of Porgy and Bess (1959).

Probably Poitier’s two most celebrated roles were as the escaped convict shackled to Tony Curtis in Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958) and as Detective Virgil Tibbs in Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night (1967), in which he starred opposite Rod Steiger’s racist police chief. Both were rousing but manipulative buddy movies in which the two leading men overcome their immense initial hostility and establish a strong rapport.

Poitier was smart, good looking and effortlessly charismatic. Critics sometimes mocked him for his perceived conformism – for not being more radical in his choices of movies. That, though, was never his strategy. As the only major black male film star of his era, he had a profound influence. By taking such a wide variety of roles, he was continually challenging deeply entrenched stereotypes. He demanded to be acknowledged as an artist and would grow hugely frustrated at those who tried to define him by his race. As the Will Smith monologue in Six Degrees of Separation attested, in his own understated way, Poitier really was a trailblazer. Smith is just one of the many contemporary stars who owe a considerable debt to him.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks