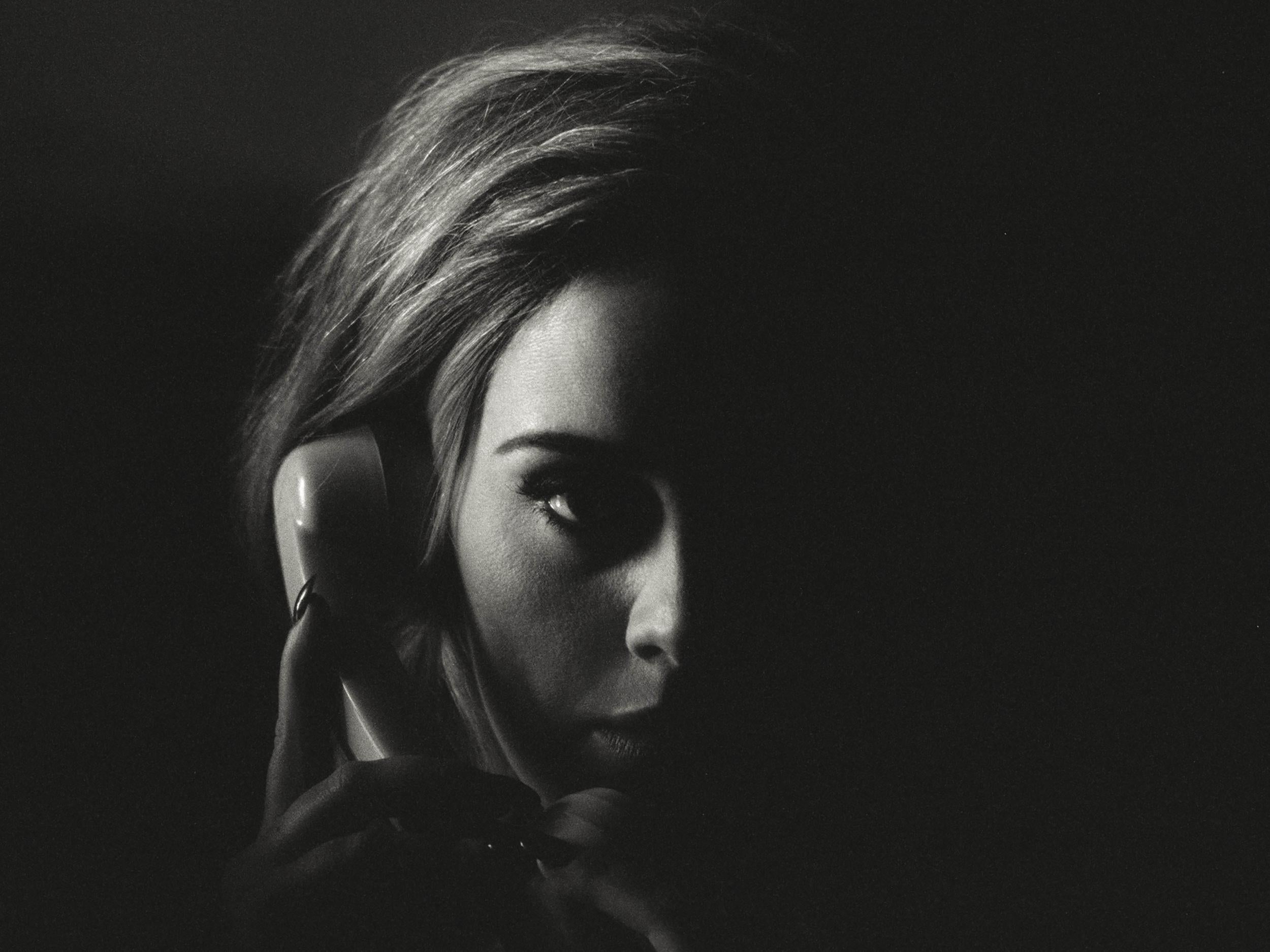

Adele's musical collaboration let-downs: Don't call me, I'll call you

Adele asked Damon Albarn and Phil Collins to write on her new album then rejected their work. But a little musical collaboration can go a long way

One thing about being the hottest singing star on the planet is that you don’t have to abide by the usual celebrity etiquette, as Adele demonstrated with her seemingly cavalier attitude towards high-profile potential collaborators on her forthcoming album. A year ago, Phil Collins was moved to call her a “slippery little fish” for the way she treated him. At her request, he had worked on a track for Adele, but never received any further response after delivering it. “I didn’t know if I’d failed the audition,” he noted pointedly, “as I didn’t hear back from her.”

Then more recently, as the release date loomed closer, news filtered through of further musical movers and shakers receiving the singer’s cold shoulder, including fruitless collaborations with top songwriter Diane Warren, the ubiquitous Pharrell Williams, and Damon Albarn, who sounded somewhat piqued after taking time out of his busy schedule to work on five tracks for her, none of which reached completion.

“It ended up being one of those ‘don’t meet your idol’ moments,” Adele told Rolling Stone this week, “I regret hanging out with him.” He had already called her “insecure” and dismissed the portion of the record he heard as “very middle of the road”. But then, how could it be otherwise? Despite her extraordinarily successful alliance with producer Paul Epworth, for 25 Adele had opted to reduce his contribution to a mere two tracks, in favour of flooding the album with exactly the same names used by every other R&B diva: the likes of Greg Kurstin, Ryan Tedder, Bruno Mars, and Swedish hit factory Max Martin & Shellback? Was Albarn right? Was she, in some sense, scared of not making the grade this time around? Or was it more a fallback strategy triggered by the trouble she experienced coming up with her signature heartbreak material in the blissful wake of commercial fulfilment and motherhood?

25 has reportedly already cost £4m to make, at least half spent on binned material – including an entire album, mercifully abandoned, themed around babies. “That’s boring,” she said recently, “so I scrapped it. I thought I’d run out of ideas.” But what’s the point of then settling for the same old ideas that have driven the music industry for the last decade? It just seems meek and craven, a decision born of commerce rather than creativity – compared with, for example, Miley Cyrus’s recent enjoyably bonkers alliance with the Flaming Lips for the free double-album Miley Cyrus & Her Dead Petz.

Cyrus’s approach is much more in line with the classic Sixties attitude to collaboration, a genuine attempt to experiment with friends, regardless of the results. When Traffic’s Steve Winwood settled in behind the Hammond organ at New York’s Record Plant Studio one evening in May 1968 alongside Jimi Hendrix, drummer Mitch Mitchell and Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Casady, they weren’t thinking of chart potential, simply of pursuing musical threads. The result was Hendrix’s longest recording, Electric Ladyland’s 15-minute blues jam “Voodoo Chile”. When Eric Clapton joined George Harrison for “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” on the Beatles’ White Album, the collaboration was born out of mutual friendship and musical respect. The same applies to Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash duetting on “Girl From The North Country”, notwithstanding the cultural significance of creating a bridge between a counter-cultural icon and a deeply conservative music genre.

Dylan and Cash were fortunate in both recording for the same label. In many cases, contractual obligations necessitated the use of playful pseudonyms to disguise identities. Who, for instance, lurk behind the names Apollo C Vermouth, Blind Boy Grunt and L’Angelo Misterioso? (answers below*). But in the late Sixties and Seventies the social aspect of the interplay between musicians was hugely important as, increasingly hidebound by their burgeoning celebrity, young stars took solace in the company of their peers. It’s a shift most clearly signalled in the hippie aristocracy assembled as the backing choir for The Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love”, a court which included, amongst others, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Moon, Eric Clapton and Graham Nash.

As the practice of collaboration with “heavy friends” became codified in band-names comprising lists of player’s names (such as Emerson, Lake & Palmer), Nash himself would go on to become an integral part of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, exemplars of the prolific interaction between West Coast musicians, in which David Crosby served as a hub linking the San Francisco and Los Angeles hippie scenes. Crosby’s 1971 solo debut If I Could Only Remember My Name is a tumult of moonlighting musicians from various bands, its music a reflection of the stoned, indulgent milieu in which it was created.

Adele and P J Harvey joint favourites as Mercury Prize shortlist announced

Show all 10As the Sixties shaded into the Me Decade, pop’s aristocratic assumptions became crystallised in the dandyish plumage of glam-rock – although to give him his due, the era’s premier collaborator David Bowie sought out not stellar successes but fallen idols such as Iggy Pop and Lou Reed, whose careers he generously renovated, and outré talents like Brian Eno, with whom he laid the groundwork for pop’s future. But by the late Seventies, punk effectively poisoned the well of collaboration by condemning the rock peerage to the dustbin of history virtually overnight. For the best part of a decade, notions of jamming or guesting became utterly infra dig, except for serial collaborator Paul McCartney, who devised a new base-level nadir for his catalogue through glutinous duets with Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder.

Despite the mother of all communal efforts, Live Aid, the notion of collaboration has never really recovered its original questing spirit – save perhaps for the extraordinary lone example of the Traveling Wilburys, the union of singer-songwriters Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, George Harrison, Jeff Lynne and Tom Petty, which actually managed to come up with a few decent songs. Unlike their Sixties forebears, most Britpop bands repelled each other in fierce rivalries, while the era’s greatest collaborator, Damon Albarn, sought out musical intrigue across a much wider terrain than a mere local scene, looking to Africa and Asia for inspirational music fellowship, as demonstrated in his Africa Express project.

So through the Nineties and Noughties, the notion of collaboration became devalued through the R&B/hip-hop fever for alliance on a flood of singles whose “featured” second artists served as commercial belt-and-braces security assurance of targeting two (or more) performers’ fanbases as potential purchasers. In many cases, the artists never actually met, a situation notoriously established when Aretha Franklin and George Michael managed to “duet” at different times and on different continents for the chart-topping “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)”, a title whose irony went unremarked at the time.

But the final indignity lies in wait for all artists thanks to the burgeoning trend for afterlife collaborations, as dead artists’ recordings are ruthlessly pillaged (without their consent, of course – management and holding companies being rather more malleable regarding their former clients’ interests) for posthumous hook-ups with singers they might possibly have despised. It’s one thing for Natalie Cole to “duet” with her late father Nat King Cole, but quite another for Elvis Presley to be saddled with not just the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra but also Michael Bublé on a new album of re-tooled favourites. Adele, you have been warned!

* Respectively: Paul McCartney (on the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band’s “I’m The Urban Spaceman”); Bob Dylan (on the Broadside Ballads compilation); and George Harrison (on several tracks, most notably Cream’s “Badge”.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies