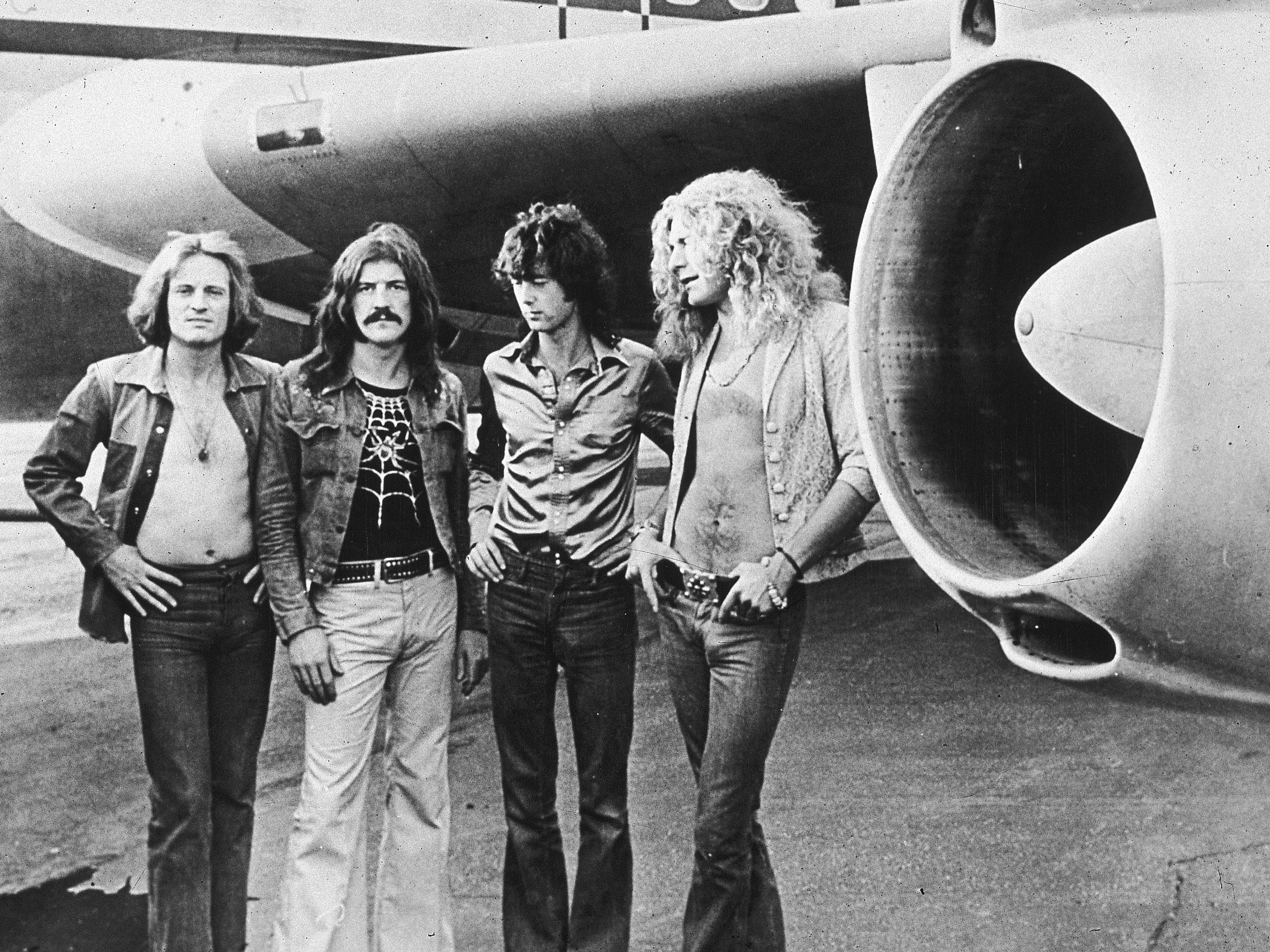

The untimely death of Led Zeppelin

It’s 40 years since the biggest rock band in the world broke up, two months after the death of drummer John Bonham. The Zeppelin myth holds that the band wouldn't go on without him, but others tell a darker tale. Mark Beaumont explores what really happened

John Bonham threw his fourth quadruple vodka of the morning down his neck and took a single bite of a ham roll. He grinned at Led Zeppelin’s assistant Rex King, charged with getting one of rock’s most mercurial and hedonistic drummers to rehearsal in a fit state to play. “Breakfast,” he said.

It would be the last of his life. Back in the car en route to Berkshire’s Bray Studios on 24 September 1980, Bonham’s mood turned sour, hinting at a devastating split approaching far faster than anyone could have imagined. “As we drove to the rehearsal, he was not quite as happy as he could be,” Zeppelin singer Robert Plant said later, recalling the events that led up to the break-up of one of the biggest and most influential bands of the Seventies, 40 years ago on Friday (4 December). “He said, ‘I’ve had it with playing drums. Everybody plays better than me.’ We were driving in the car and he pulled off the sun visor and threw it out the window as he was talking. He said, ‘I’ll tell you what, when we get to the rehearsal, you play the drums and I’ll sing.’”

At rehearsal, for the band’s first US tour since 1977, in support of their eighth album In Through the Out Door, Bonham – Bonzo to his friends – never slowed down. Having collapsed onstage during the third song at a show in Nuremberg a few months earlier (the band claimed he had “overeaten”), his furious alcohol intake had made him prone to blackouts, and as he worked his way through a reported 40 units of vodka during the 12-hour rehearsal his playing began to deteriorate. “Bonzo had been getting a bit erratic,” said Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones. “I can’t say he was in good shape, because he wasn’t. There were some good moments during the last rehearsals… but then he started on the vodka… I think he had been drinking because there were some problems in his personal life.”

When the band retired to guitarist Jimmy Page’s home at the Old Mill House in Windsor for the night, Bonham passed out on a sofa at midnight and was put to bed by an assistant, lying on his side. The following day, when he hadn’t arrived for rehearsal by 1.45pm, Jones and Zeppelin’s tour manager Benji Lefevre went to check on him.

“We tried to wake him up,” Jones said. “It was terrible. Then I had to tell the other two… I had to break the news to Jimmy and Robert. It made me feel very angry – at the waste of him.”

Bonham’s death from inhalation of vomit that night, aged just 32, didn’t just mark the tragic loss of one of rock history’s most celebrated drummers, famed for his incendiary 20-minute live solos and the bedrock of Led Zeppelin’s elemental power – “John Bonham played the drums like someone who didn’t know what was going to happen next, like he was teetering on the edge of a cliff,” said Dave Grohl – but also the demise of a band that would come to represent the cornerstone of both classic rock and heavy metal.

The North American tour was cancelled and six weeks later, on 4 December, Led Zeppelin announced their dissolution with a short press statement. “We wish it to be known that the loss of our dear friend and the deep sense of undivided harmony felt by ourselves and our manager, have led us to decide that we could not continue as we were.” The band swore – publicly at least – not to continue without a founding member and, bar the occasional charity and anniversary reunion, have kept their word ever since.

“After losing John I didn’t want to touch the guitar, and that feeling lasted for quite a few months,” Page writes in his new book Jimmy Page: The Anthology, while Plant recently spoke about the split inspiring him to go solo during his Digging Deep podcast. “I was just 33,” he said, “and the whole [of] my last previous 12 years have been in the warmth and occasional tepid and freezing climate of Led Zeppelin. So when we all lost John there was only one thing to do and that was to carry on, to try and carry on and distance myself if I could from the wondrous shadow of the past.”

Bonham’s son Jason, who performed with the remaining members at several one-off shows, told Billboard that after their much-lauded 2007 reunion at the Ahmet Ertegun Tribute Concert at London’s O2 he’d asked Plant if Led Zeppelin were going to reform. “He said, ‘I loved your dad way too much… I can’t go out there and fake it. I can’t be a jukebox. I can’t go out there and try to do it that way’… He told me, ‘When your father left us, left the world, that was it for Led Zeppelin. We couldn’t do what The Who did. It was too vital.’” Elsewhere, Plant has been more figurative. “It would be like sleeping with your ex-wife again,” he’s said, “without having sex.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Zeppelin were certainly behemoths of the Seventies rock kingdom. Over 12 years and eight albums they recast the blues rock, folk psychedelia and powerhouse pop of Sixties greats such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Who (along with plenty of Tolkein references and “borrowed” blues tunes) into a primal new form of hard rock: “the heaviest band of all time” according to Rolling Stone. Along the way they sold anywhere between 200 and 300 million copies of seminal albums such as Houses of the Holy, Physical Graffiti and their self-titled early records, and condensed the hedonistic and mystical leanings of the likes of Keith Richards, Jimi Hendrix and George Harrison into a unified symbol of classic rock mythology, peppered with notorious tales that make uncomfortable reading in 2020: under-age girlfriends, the red snapper incident, Page’s rumoured Satanic rituals.

Their final two albums, Presence (1976) and In Through the Out Door (1979) might not have matched the critical acclaim or phenomenal sales of Physical Graffiti or 1971’s 37 million-selling Led Zeppelin IV, but both topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic and went multi-platinum. When this Zeppelin went down it wasn’t, from the outside at least, in flames. Hence, the band’s bow-out in 1980 has become seen as a benchmark of brotherhood in rock’n’roll. By emphasising the sacred, almost psychic bond between a close family of tuned-in musicians, it was seen as a statement of magical creative unity that many acts have adhered to since: acts as diverse as Beastie Boys, A Tribe Called Quest, The Cribs and Coldplay have decided that their bands would cease to exist if one member was lost.

Beyond their vast musical impact then, Zeppelin’s split also helped instil, in more righteous acts, the tenet of music over money. “Led Zeppelin wasn't a corporate entity,” Page told Rolling Stone in 2012. “Led Zeppelin was an affair of the heart. Each of the members was important to the sum total of what we were. I like to think that if it had been me that wasn't there, the others would have made the same decision. And what were we going to do? Create a role for somebody, say, ‘You have to do this, this way?’ That wouldn’t be honest.”

All was not quite as Musketeers-like as it seemed, however. “The ‘couldn’t do it without him’ story is just an excuse,” argues Mick Wall, author of Led Zeppelin biography When Giants Walked the Earth, “Zeppelin were in a completely awful place when Bonham died. It’s one of the reasons he died, they were rotting from the head down.” Wall argues that the heroin abuse and tragic events of the band’s late-Seventies era had exacerbated animosities between Page, Plant and Bonham and driven the band to the brink of collapse some years earlier.

Struggling with touring and recording in the aftermath of a 1975 car accident on the Greek island of Rhodes, which almost killed his wife Maureen and confined him to a wheelchair for several months, Plant had long felt frustrated with the Zeppelin machine. “I was furious with Page and [band manager] Peter Grant,” he told biographer Chris Welch. “I was just furious that I couldn’t get back to the woman and the children that I loved. And I was thinking, is all this rock and roll worth anything at all?”

The 1977 US tour was, according to tour manager Richard Cole, “f***ing horrible. There was no camaraderie between anyone.” Fuelled by vodka, Bonham was becoming unruly and violent – a written set of backstage rules warned journalists not to look him in the eye “for your own safety”. Page’s heroin habit, meanwhile, made him a surly presence, darkening the mood in the Zeppelin camp and spitting at sound technicians mid-set. “There were bodyguards everywhere, and that was a real big sea change from ’75 to ’77,” journalist Jaan Uhelski told Barney Hoskyns for his 2012 oral history Trampled Under Foot. “There was just a cloud that seemed to hang over everybody.”

“It was just a mess,” Plant added. “Where was the actual axis of all this stuff? Who do I go to if it’s really bad for me? There was nobody. Everybody was insular, developing their own worlds.”

That last ever American Zeppelin tour was cut short in New Orleans when Plant received word of the death of his five-year-old son Karac from a stomach infection. In the wake of such a devastating loss the band were put on hold; Plant no longer cared about strutting around stages singing “Whole Lotta Love”. “I lost my boy,” he told Rolling Stone, “I didn't want to be in Led Zeppelin. I wanted to be with my family.” “I didn't really want to go swinging around,” he explained to Q in 1990. “‘Hey hey mama, say the way you move’ didn't really have a great deal of import anymore.”

Quitting all of his drug habits in one day, he even strongly considered swapping life as a golden rock god for the blackboard jungle. “All of us had been thinking about what would happen next because the illusion had run its course,” he told the BBC in 2010. “I’d already lost my boy and then you think, ‘I really have to decide what to do.’ I applied to become a teacher in the Rudolf Steiner education system. I was accepted to go to teacher training college in 1978. I was really quite keen to just walk.”

“I just thought there was something far more honest and wholesome about just digging in and putting the ego away in the closet,” he told GQ in 2011. “Because no matter what we say, entertainers are usually quite insecure, wobbly characters underneath – and maybe that bit of glory or that bit of expression or whatever it is compensates in some area. But I thought I should be rid of it.”

His bandmates’ differing reactions to the tragedy drove further wedges between them. “During the absolute darkest times of my life when I lost my boy and my family was in disarray, it was Bonzo who came to me,” Plant said in 2005. “The other guys were [from] the south and didn’t have the same type of social etiquette that we have up here in the north that could actually bridge that uncomfortable chasm with all the sensitivities required… to console.”

Wall cites Page not attending Karac’s funeral as an unforgivable breaking point, dissipating Plant’s “mystique” for his guitarist foil and giving him the power of being willing to walk away. “Bonzo was the only one who went to the funeral,” he said. “Plant understood that when you’re with people that are deep into heroin – multi-millionaires with ounces and ounces, their whole life, their religion, their heart is all heroin – it produces bad s***. Plant being the eternal hippy who believes in karma, felt convinced that every rotten thing that had happened to him and Zeppelin, which had begun in 1975 with the terrible car crash, all related back to the fact that Zeppelin had taken a very dark turn… Plant left the group at that point, he was gone, they just didn’t announce it because they were hoping to get him back.”

It fell to Bonham and Page to hold the band together. “I was thinking about leaving the group, but Jimmy Page kept me from doing it,” Plant told German magazine Bravo at the time. “He said without me, the band’s nothing. He wanted me to take a break until I felt ready for playing again. I realised that we are more than business partners. We are real friends.”

“The only reason Plant went back in 1979 was because Bonzo more or less begged him,” says Wall. “After Jimmy became completely incapacitated [by drugs] it was all about keeping Robert happy. The way they kept him happy on those final shows in Europe in 1980 was to cut their hair, stop wearing flares, ‘let’s not do “Stairway To Heaven”, let’s make the songs shorter and tighter’.”

Jones remembers 1980 as “the point where we had all come back together again – we had high hopes it was all coming right”. But according to Wall, “Plant could hardly bear to be in the same room as Page… They were completely in disarray, utterly hanging on by a thread. Page, who was literally over the other end of the rainbow, a major junkie for at least five years at that point, beyond Keith Richards, he had it in his head ‘we’ll go to America and it’ll rekindle the spark’. When Bonzo died, everybody got found out that day, the whole rotting edifice exposed itself.”

Bonham’s death was a definitive full stop for Plant. “John had been incredibly supportive to me,” he told the BBC, “so to lose him, that was the end of any naivety. It was very evident that my last connection was severed. As far as strong affairs of the heart and a confederacy, it was gone.”

Following 1982’s swansong rarities compilation Coda, the band retreated into myth-shrouded legend. A reunion for the Philadelphia leg of Live Aid with an un-rehearsed Phil Collins sitting in fresh from a Concorde flight from Wembley only justified Plant’s stance that it wouldn’t be Led Zeppelin with any other drummer. “It was a f***ing atrocity for us,” Plant said. “It made us look like loonies.”

As a result, the band turned down $90 million each to tour the US in the wake of Live Aid, and Plant also scuppered plans for a year on the road following the O2 reunion. Page and Jones rehearsed with Steven Tyler standing in for Plant and Jason Bonham on drums, but that unprecedented payday never happened. “The Roger Waters tour around the same time grossed about $700 million,” Wall says. “Zeppelin would’ve doubled that. Robert walked away from it to do a tour of college towns with Alison Krauss, partly because the whole experience of getting back together was so awful. At the O2, Jimmy was in his own enclave with armed guards.” The Zeppelin fables of recent years have been more financial than hedonistic; in 2014, rumours circulated that Plant had ripped up an $800 million offer from Richard Branson to reform.

Their split might have come about due to internal fractures more than band-of-brothers unity, and their reluctance to tour may be far from unanimous, but as Led Zeppelin’s influence swamped the coming decades, inspiring vast swathes of acts as cool as The White Stripes and as corny as The Black Crowes, Plant’s refusal to capitalise on their history since Bonham’s death has smacked of a certain nobility, leaving the Zeppelin legacy untainted and the arcane fantasy of their mystical bond intact. The truth may be messy, sour and inconvenient but, with Zeppelin, the myth always mattered most.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks