‘From national jokes to national treasures’: The rise, fall and rise again of Take That

A new Netflix documentary offers the most comprehensive look yet at the remarkable story of one of the UK’s biggest boybands. Roisin O’Connor speaks to director David Soutar about getting the band to trust him with telling it

Many of us might think we know the Take That story. Nineties pop sensation. Hordes of screaming fans. Gary Barlow’s frosted tips! Then there was the split, Robbie Williams going solo, the band disintegrating. A triumphant reunion years later, reconciliation. But these are merely the flashbulb moments – what about the gaps in between?

Enter Netflix’s eye-opening new Take That documentary. Directed by David Soutar, the filmmaker behind 2018’s brilliant Bros: After the Screaming Stops, the three-part series digs deeper into the mechanism of what propelled five young lads to fame in the first place, and the individual stories that haven’t been told until now. Jealousy, insecurity, and plenty of grievances that weren’t aired until it was too late. “I think all of us are wise enough, having gone through these decades with them, hand in hand with their music and their story,” Soutar says. “But there are twists and turns in there that people don’t really know, or have forgotten.”

Unlike many other music documentaries today, Take That sees the current trio – Barlow, Howard Donald and Mark Owen – cede creative control to Soutar and production company Fulwell Entertainment. A gamble, given how brutal and uncompromising the Bros documentary was. But, Soutar says, that’s the only way it ever works: “The audience can sense if a band’s had their hand in it, so we said to them from the outset, you’ve got to be brave enough to hand us your story. Let us be the curators of your tale.”

Given Williams has already had his own feature film and Netflix documentary, you would also understand if Soutar had been tempted to make this the Gary Barlow show. But the series never feels one-sided. Everyone has a voice.

It was painful for Barlow and co to cast their minds back, Soutar says, and watching the series, it’s no surprise. Every crushing low, including the flopped solo careers and the frequent jabs at Barlow’s weight, is laid out in gory detail; there’s no attempt to add a sheen of rock’n’roll glamour to what the band were going through. In a “sadistic” kind of way, Soutar admits, it was gratifying to see how the final cut “made them feel what they felt back then; really tough, complicated feelings. They said it was a tricky thing to relive those moments – they all worked very hard to get where they are now, personally and professionally.”

The documentary was originally a two-parter, until Soutar realised that wouldn’t do the story justice: “That’s 35 years in 120 minutes. It’s five characters, four decades. How on earth do you pack that in?”

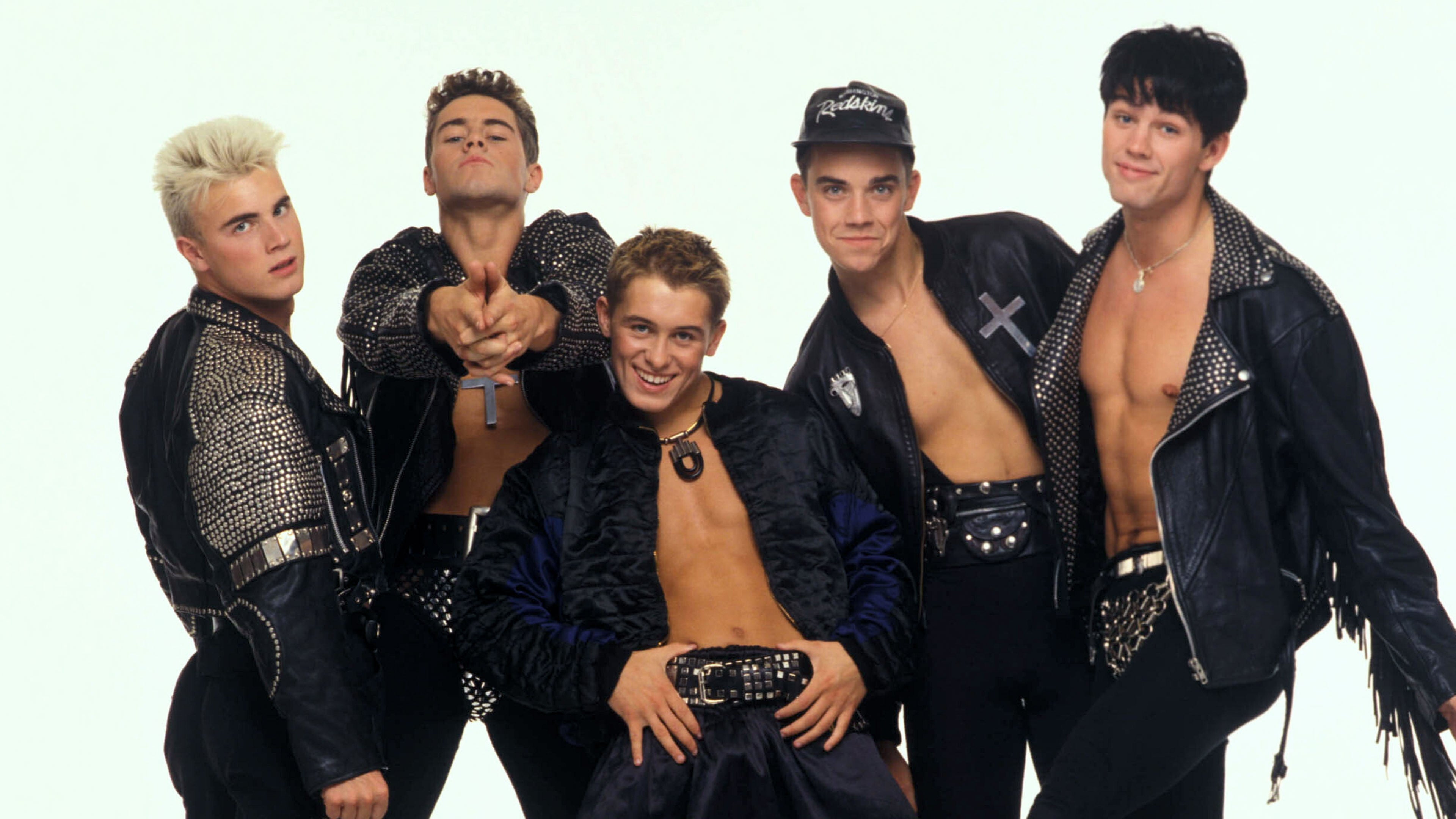

Episode one takes us right back to the beginning. It was 1990, and five fresh-faced boys – Barlow, Williams, Owen, Donald and Jason Orange – were assembled in Manchester by manager Nigel Martin-Smith as the UK’s answer to New Kids on the Block. Take That was built around the 18-year-old Barlow, who’d been performing in clubs since he was 15 – he was joined by manual labourer Donald, 22; dancer Orange, 19; bank employee Owen, 18; and aspiring entertainer Williams, 16.

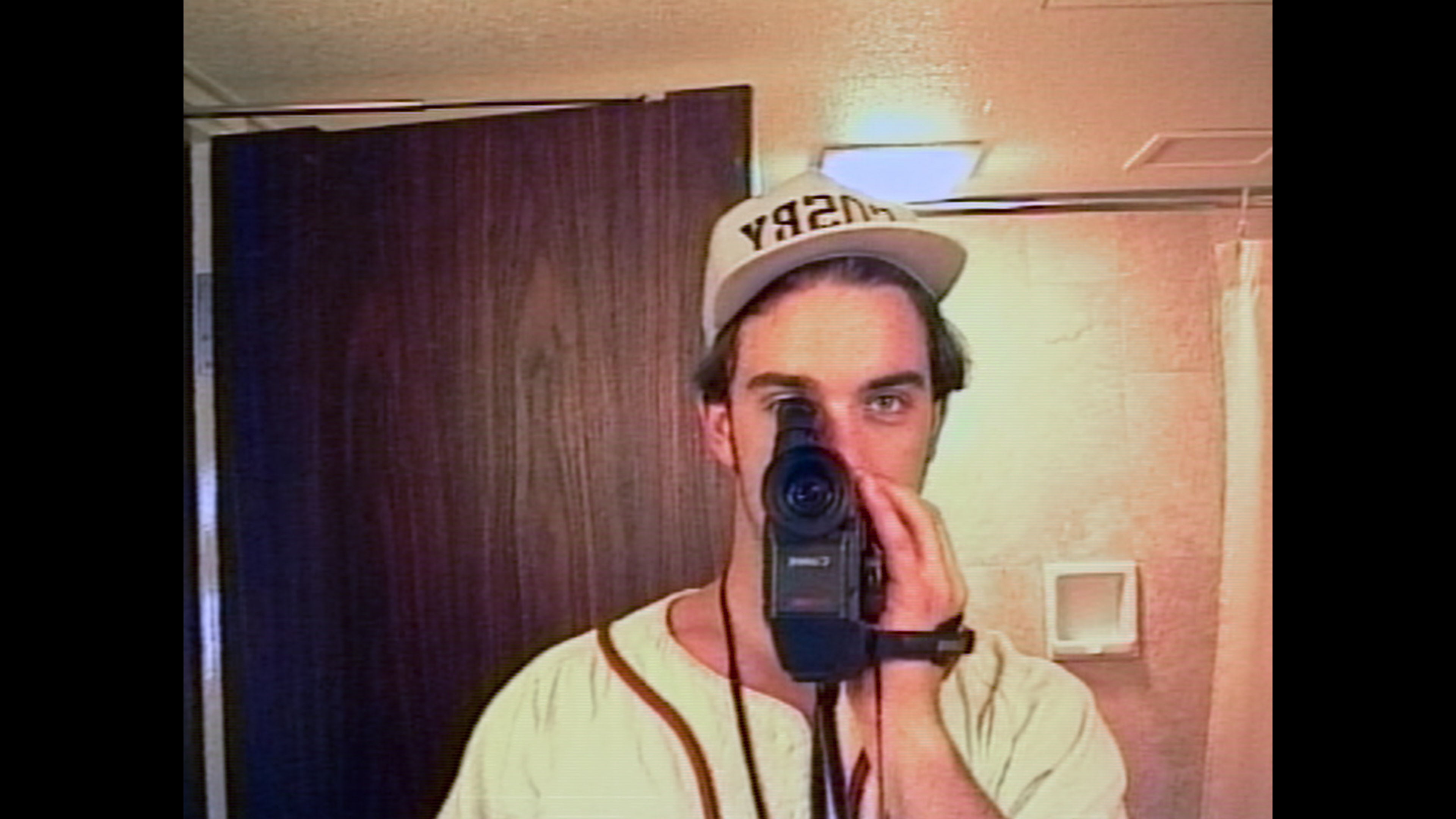

You don’t see the present-day band on screen in the series at all. Instead, the narrative is provided through voiceovers and old interviews (Orange and Williams didn’t contribute new commentary). Much of the footage is from a treasure trove of tapes the band had lying around in an Ikea bag; most of it had been filmed by Donald himself. “They had a videographer before anyone else!” Soutar marvels.

Take That did a lot of things before anyone else. For Soutar, they were the blueprint for the manufactured boyband: “Everyone now knows the formula, but Take That invented it.” In the early years, they didn’t know how to generate a fanbase and were figuring out their identity. Initially, they targeted an older audience before realising they could connect with teenagers. They were mobbed at an under-18s event and decided to do a tour of school assemblies – there’s some brilliant footage of the band bouncing around on stage in front of nonplussed kids and teachers. But eventually, they took hold, and fans started to turn up outside their homes.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

The shows stacked up: schools, theatres, gay clubs. “They were making it up as they went along,” says Soutar. It worked: manager Martin-Smith told them to give up their day jobs. “We’d done everything,” Barlow says in the documentary, “except have a hit.”

The turn of the Nineties, we hear Barlow explain, was dominated by “faceless dance music” – think “Infinity” by Guru Josh – while the kind of pop ballad he was writing felt old-fashioned. But they believed they would succeed, encouraged by Martin-Smith’s ego-stroking and their own assurances to one another. Their manager remortgaged his house so they could put out their first single, “Do What You Like”, complete with a bawdy music video that styled them like S&M Chippendales.

“We had to make an impression,” Owen says in the show, somewhat downplaying the video’s studded leather jackets, bejewelled crotches and close-ups of their naked buttocks being smothered in jelly – it was promptly banned from daytime TV. But sex sells, the band understood, and it got them a label deal, too. Around this time, Barlow was putting himself under a huge amount of pressure as the band’s songwriter – but their next song, “Once You’ve Tasted Love”, never reached the Top 40.

“I felt like I’d failed,” he admits on camera. He wondered if his bandmates were secretly badmouthing him. Not long afterwards, though, Barlow came up with “Pray”, their first No 1, which saw them crowned the biggest pop band in the UK.

Even by the end of the first episode, though, just four years into the band’s career, the cracks are showing. For all their growing success at that time, the other members were becoming jealous of Barlow’s status – in particular Williams, who wanted to be loved by Martin-Smith as much as his bandmate was.

The screaming girls had also started to lose their appeal, particularly when they stood outside the group’s hotel room all night long, singing Take That songs. Walking down the street was a nightmare. So, while “Back for Good” in 1995 was a huge hit for them, leading to a late-night TV booking in the US, it was also “the beginning of the end” for the band, according to Owen. In stripped-back performances of the song, Williams looks completely checked out. Behind the scenes, he was spiralling, drinking himself into oblivion every night.

Williams quit in July 1995, not long after being photographed partying with Oasis at Glastonbury. His bandmates had given him an ultimatum: sort yourself out, or leave. The rebellious Williams announced his departure to the press along with his plans to be a solo star. While the rest of Take That swiftly crumbled, Barlow had to watch Williams score a monster hit with “Angels”, which was followed by TV spots, awards, and then a Glastonbury performance in 1998.

Barlow, meanwhile, came back to the UK with his tail between his legs after a flop of a radio tour, to be told he was being dropped as a solo artist by his label. He went home to Cheshire while the media and entertainment industries continued to mock him relentlessly. “I saw it all, and watched it all,” Barlow says in the show. Then came the Brit Awards, and a Little Britain sketch with Matt Lucas as Barlow with a beer belly. “Sorry Gary,” Williams notoriously said, accepting another award. “But I was always the talented member of the band.”

I went on this mission... I’d killed the pop star

Barlow started to eat. There was a period of around 13 months when he didn’t leave the house once. The weight piled on, and people stopped recognising him. “I went on this mission then... I’d killed the pop star,” Barlow says. He developed bulimia. He also became the favourite punching bag of his former bandmate – Williams was egged on by the tabloid press, who ran his mocking comments all over their front pages.

And it wasn’t just Barlow who struggled. Howard Donald was a self-described “nobody” at school who’d “never dreamt of being successful”. On stage, though, he was a “superhero” performing to thousands of adoring fans every night. In the silence that followed, he fell into a depressive state and contemplated suicide. Jason Orange tried acting while the others pursued solo careers, but he didn’t enjoy it, so stopped. Mark Owen was dropped from his record label after releasing just one album. It would be 10 years before fans got to see them together on stage again.

“One of the huge things I realised was just how brave they were with the treatment they had from the press,” Soutar says. “It was brutal – we know that – but they didn’t have to try again. They could have given up; said, ‘Let’s not put ourselves or our families through that again.’” But try again they did, and episode three charts the triumphant Take That comeback without Williams: their 2005 reunion, and a return to the charts with hits like “Rule the World”, “Greatest Day”, “Shine” and “Patience”. There was a scary conversation with Martin-Smith; the band wanted a fresh start, which meant ditching the man who’d “invented” Take That.

But they wanted it to be right. “I wanted it to feel good for everyone,” says Barlow, who is wonderfully candid throughout, “and I suppose that was new. I didn’t really care about anybody else in the Nineties, I just wanted it to be alright for me.”

The band had an emotional reunion with Williams in 2010, for which the re-formed five-piece released a new album, Progress (one of the fastest-selling albums of the century). At the time, Williams was “bored, scared and lonely” in Los Angeles, and felt he had nothing more to say in his own records. But there was a lot he wanted to say to Barlow, and vice versa. “In about 25 minutes, we’d put to bed things that had haunted us for years, and it felt like we could move forwards after that,” we hear Barlow say.

Now they’ve proved themselves to each other, too – Take That returning with their massive Circus tour, Williams smashing a Beatles record with his latest No 1 album, Britpop – perhaps there’s a better sense of contentment among them all.

“People don’t realise how much contact they’ve had over the years, even when the world was pitting them against each other, but it was semi-constant,” Soutar says. “It’s such a strange world for them, because they’ve realised that they’re stronger than the sum of their parts. They need each other.” Footage of the band in the studio, writing together, shows Take That with a newfound purpose. It’s incredibly moving to see them making space for each other, considering one another’s feelings, and then how that paid off with the reaction to their new music. As Owen puts it: “We needed to come back as equals.”

“The third episode was really the journey from national jokes to national treasures,” Soutar says. “The British public and press do not let anyone do that. And somehow, probably because they were brave enough to do it, and they were human enough, it happened.”

‘Take That’ is on Netflix now

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

If you are based in the USA, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Helpline on 1-800-273-TALK (8255). This is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

If you are in another country, you can go to www.befrienders.org to find a helpline near you.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks