The Velvet Underground’s Loaded at 50: How being ignored birthed a classic album

Lou Reed left soon after it was recorded; John Cale was long gone; so how did the last gasp of a great, dying rock band become one of the most influential records of all time? Mark Beaumont traces its troubled creation

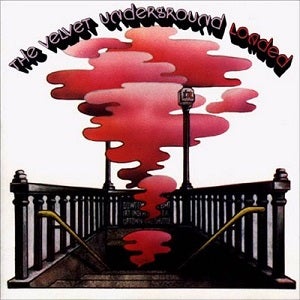

When the needle first dropped on Loaded, the fourth album from enigmatic New York art rockers The Velvet Underground, 50 years ago today, their few in-the-know followers must have considered it some kind of situationist prank. After three years of indulging the wayward and provocative ways of Andy Warhol’s musical muses – where the sweetest melodies embraced the harshest feedback, hard drug addiction and perverse sexual peccadilloes were no longer taboo, and drummers played standing up in storms of strobe – they were tuned in to the twists and challenges that would see the Velvets hailed as one of the most influential bands of all time, once the world caught up.

The seminal 1967 debut album The Velvet Underground & Nico had incorporated psychedelic dream pop, viola-laden sex drones, noise rock freak outs and transgressive rock’n’roll heroin confessionals. Its “anti-beauty” follow up White Light/White Heat was even more extreme, culminating in 17 cacophonous minutes of two-chord clatter rock about a 19th-century drug orgy. The self-titled third was an intimate folk affair and now, as the FM radio-friendly choruses of “Sweet Jane” and “Rock & Roll” chugged from the speakers, were they really playing tattered-edge country rock? Subversive genius, surely?

In fact, Loaded – the band’s last album with primary songwriter Lou Reed – was one of rock’s most impressive death splutters, and its story a case study in what happens when brilliance goes unnoticed. You get experimental doubling-down. Unbroachable creative schisms. Dramatic departures, major shifts of direction and, ultimately, last-ditch grasps at mainstream success before the whole thing collapses in on itself.

Uniquely, the Velvets endured all of this while maintaining an impeccable quality level. Their Andy Warhol “produced” (well, he was there) debut was a seismic influence on a vast array of alt-rock acts: noisemongers like The Jesus & Mary Chain, Joy Division and Spiritualized; krautrock drone pioneers Kraftwerk, Faust and Can; art-rockers like REM and Patti Smith; even winsome indie-pop acts such as Belle & Sebastian owe huge debts to a record that essentially invented alternative music as we know it. Yet, after three years of intense invention and conflict that left the band almost unrecognisable and on the verge of disintegration, Loaded is still considered almost as great an influence on punk and US radio rock. The New York Dolls, Television and The Modern Lovers were amongst the acts that would take its ragged cues and set about moulding modern rock in its image, while long-term Velvets acolyte David Bowie covered its most famous track “Sweet Jane” live, honouring its formative influence on his Ziggy era and the surrounding glam scene.

“‘Sweet Jane’ has that kind of bash-it-out three-chord catchiness that would had been very easily absorbed and adapted by groups like Mott The Hoople and solo artists like David Bowie,” says Richie Unterberger, author of comprehensive Velvets biography White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day by Day. “Something like ‘Sister Ray’ [from second album White Light/White Heat], it’s hard to match that cacophony of noise. But a more straightforward guitar-oriented song like ‘Sweet Jane’, for groups that wanted to do something that was more pared down, you could use it to make a statement.”

The roots of Loaded are embedded in the Velvets’ thwarted ambitions. After their dark, lo-fi and ground-breaking debut had slipped by almost unnoticed by a record-buying public entranced by the sonic technicolours and sherbet military suits of Sgt Pepper, 1968’s White Light/White Heat had gone further still, intensifying their experimental art-rock edge. It was a trait central to the band’s aesthetic, encapsulated when their manager Andy Warhol made them the centrepiece of his 1966 Exploding Plastic Inevitable multimedia roadshow, projecting 16mm films onto them as they performed and bombarding them with a stroboscopic light show so intense they took to wearing shades onstage.

Yet, despite its stated intentions to challenge and upend mainstream pop forms, White Light/White Heat’s failure to build them a substantial cult following exacerbated the creative struggle between the melodic rock’n’roll focus of Lou Reed and the viola tormenting avant-garde leanings of his more experimental foil John Cale.

“[Cale’s] background was much more in contemporary classical and avant garde music than rock’n’roll,” Unterberger explains. “Initially it was a great combination to have Lou Reed’s gutsy rock’n’roll and John Cale’s more experimental side, [but] it seems like by 1968 John Cale wanted to get farther and farther out and amplify the sound that you hear in the most extreme Velvet Underground songs. Lou Reed I think wanted to focus more on songs that were more conventional and accessible… It seems like there was no way of reconciling that.”

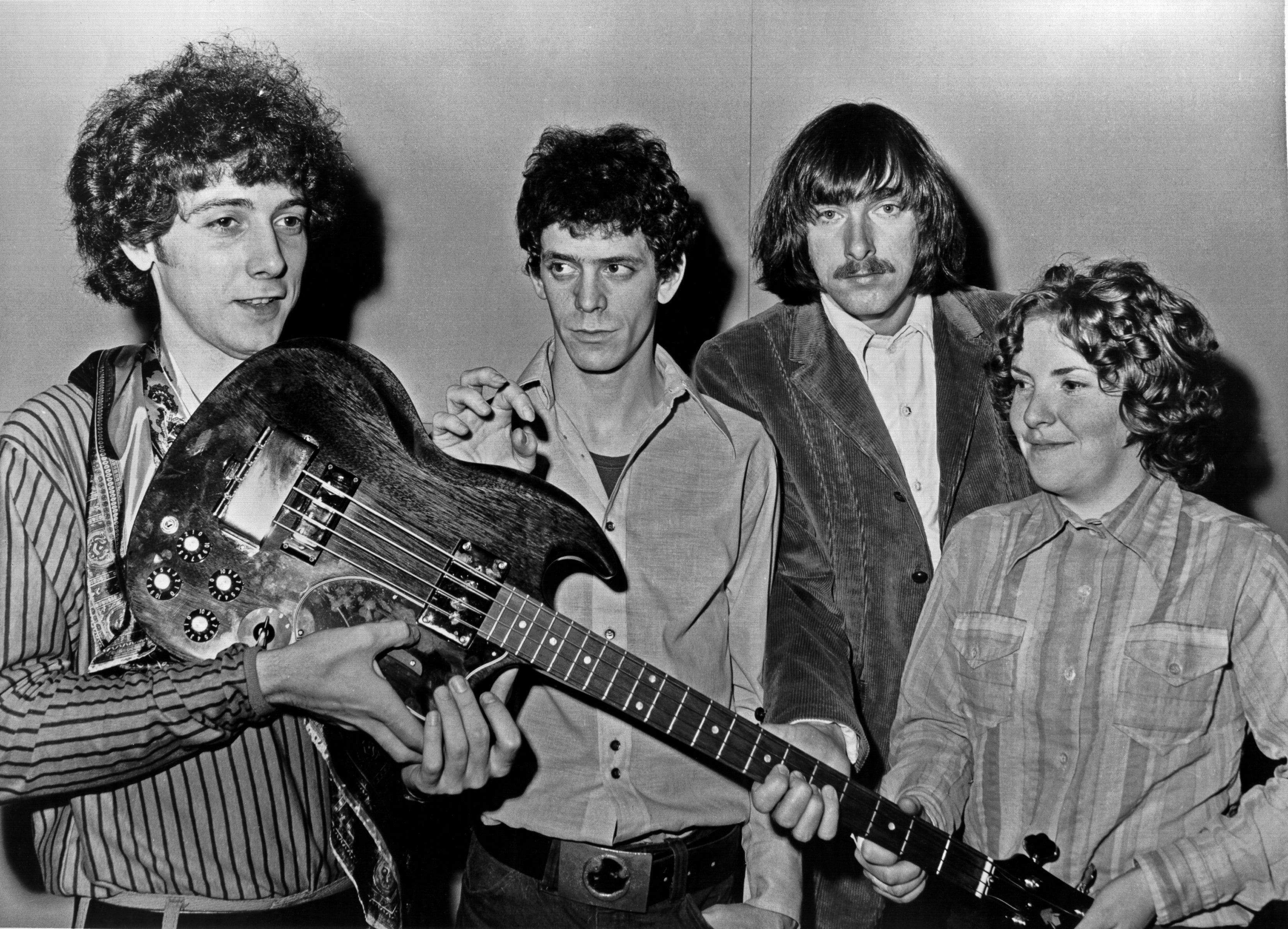

Reed himself never fully explained why he chose to gather guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Maureen “Moe” Tucker (who famously gave the band their imposing backbeat by playing upturned drums with mallets, standing up) together after White Light/White Heat stalled at the bottom end of the US Top 200 and insisted that either Cale was fired or the band was dissolved. Insiders claimed Reed privately revealed that Cale’s ideas were getting too bizarre, such as recording their third album with the amplifiers underwater, but there may have been ego issues at play, too. “It’s also been speculated that Reed was jealous of John Cale,” says Unterberger. “Cale cut a very flamboyant figure on stage.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“They seem to me to be both very strong type A personalities,” Cale’s replacement Doug Yule told Unterberger for Day by Day. “They’re very driven, they have an idea, and they want to move that forward. If they’re not working together, then they’re butting heads… My own value at that point to Lou was that I was a much more deferential person. I’m much more of a facilitator than I am a leader.”

Yule joined the band on bass just weeks before the recording of 1969’s third album The Velvet Underground, despite only having seen the Velvets play once and never having played bass before.

The Velvet Underground was a far quieter, folk-inflected shift in direction, an intimate album shorter on references to hard drugs and S&M and dotted with love songs to Reed’s college sweetheart Shelley Albin. One of the two mixes released was dubbed the “closet mix” by the band because it sounded as though Reed was singing in a wardrobe. “I thought we had to demonstrate the other side of us,” Reed said, “otherwise, we would become this one-dimensional thing, and that had to be avoided at all costs.“

“[Reed] explained in a few interviews that he felt like the first three Velvet Underground albums were different chapters in a novel that just happened to be presented on a record,” Unterberger says. “The Velvet Underground & Nico was somebody exploring various facets of experience for the first time, probably. White Light/White Heat was that character or those characters taking the experimentation to the extreme, almost so that it might threaten their lives. And The Velvet Underground he saw as a retreat from that, the character or characters becoming more reflective and thinking more about what these experiences meant.”

The Velvet Underground also flopped and the band were dropped by MGM Records, so freshly signed to Atlantic subsidiary Cotillon and under all of the commercial pressure that entailed, their fourth album was set up as something of a make-or-break affair. “They wanted to make a record ‘loaded with hits’,” says Unterberger. “They weren’t getting that wide recognition in the public and I think, even if it wasn’t consciously thought of at the time, it was ‘this is our last shot with the group that we have to get that recognition that we deserve. We don’t want to keep scuffling for survival, even if we’re making great records we want something more than that.’”

“Its purpose was to garner FM airplay,” Yule told Unterberger, “Those mainstream FM album-cut stations were the other route to good gates, money. [Loaded] was designed to reach that.”

Moe Tucker, cited by Yule as the “anchor” of the band and “the glue that kept things rolling many times when they might have otherwise come into pieces”, was too pregnant to play drums when it came time to record Loaded, and her absence caused the band to begin to rattle loose at the edges. As Reed and Yule pieced together Reed’s songs in the studio rather than play them as a group, Morrison drifted away from sessions, feeling dislocated. “He was unhappy with Loaded,” Yule told Unterberger. “He felt that he had been effectively shut out because Lou and I were kind of bubbling around doing all this stuff. I think that was kind of a spin-off of the whole Maureen thing, and it never should have happened. After a while, he just stopped coming. He’d say, ‘Well, you need me to record anything?’ And we’d say, ‘Well, we don’t know.’ ‘OK, well, call me if you need me.’”

I think it was exhausting for him to keep up with Lou Reed’s varying moods

“It seems like [Morrison] was retreating psychically from heavy involvement with the group,” says Unterberger. “I think in part that’s because he was seriously buckling down to graduate from college, but also I think he was tired of… not exactly fighting with Lou but Lou always having his way… I think it was exhausting for him to keep up with Lou Reed’s varying moods and also to adjust to what he wanted without having nearly as much of a creative say.”

With part-time drummers including Yule’s brother Billy filling in for Tucker and enough songs coming out of Reed’s bag to make a double album, Loaded emerged as a tight 40-minute rock out that squealed and span across the mainstream like a bald-tyred roadster. The opening “Who Loves the Sun”, a psych-pop anthem redolent of George Harrison’s Abbey Road highlights, sounded like both a homage to and an elegy for the Sixties dream. “Sweet Jane” and “Rock & Roll” were the missing links between The Stones and The Stooges, fermenting punk in Reed’s coiled streetwise snarls, while “Lonesome Cowboy Bill”, “New Age” and “Cool It Down” dovetailed messily with the emerging Americana of The Band and Neil Young.

The moments of hippie sun-worship, rock’n’roll heroics and cowboy caricature were populist smokescreens too, hiding tales of prostitution, homelessness, the souring of Sixties idealism and, in “New Age”, a tale of an obsessive fan hunting down an ageing actress, a premonition of today’s stan culture. “With Loaded, I think the Velvets finally did something in full colour,” Yule told Unterberger, and its tones soon began to bleed into the 1970s. The breezy freeway rock of “Sweet Jane”, “Head Held High” and “Rock & Roll” was as fundamental to FM stalwarts like The Cars and Tom Petty as early new wavers like The Modern Lovers and glam pioneers like Bowie, whose Ziggy Stardust era played heavily on the sort of corroded rock’n’roll found on Loaded. You suspect even The Eagles learnt a thing or two about billowing country epics from the closing “Oh! Sweet Nuthin’”.

As The Velvet Underground’s stature ascended over the coming decades, their fourth album was rediscovered by later generations. Graham Coxon has cited Loaded as a primary influence on Blur, and Primal Scream not only emulated its grimy rock’n’roll but slyly borrowed its double-meaning title for one of their biggest Nineties hits. Just as Reed wrote “Rock & Roll” about having his life changed by hearing Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel” on the radio as a child, it in turn would fire up future pop subversives.

In 1970 though, Loaded spelt the end of The Velvet Underground. Even before it was mixed Reed, disillusioned at his ground-breaking arthouse band being reduced to piecing together pop hits in the studio – and still getting nowhere commercially – quit the band midway through a residency at New York club Max’s Kansas City. As the remaining original members also dropped away, Yule was left trying to keep the band’s name alive over sporadic promo tours and 1973’s one-man follow-up album Squeeze.

Reed would disown Loaded – “I left them to their album full of hits that I made,” he’d say – but by the time of its extensive 1997 reissue, he’d gained the same sort of perspective as its many acolytes and imitators. “It’s still called a Velvet Underground record,” he told David Fricke in the liner notes, “but what it really is is something else.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks