Activists question Japan’s ‘lack of urgency’ on climate action as G7 begins: ‘We need a grander vision’

Experts tell Stuti Mishra that climate action measures at the G7 summit might be coming in too late as Japan’s own track record on climate action is pushed into the spotlight

Japan’s vision for G7 lacks urgency when it comes to the climate crisis, say activists who have pointed out that the summit might not meaningfully address the plethora of stark, climate-related warnings sounded recently.

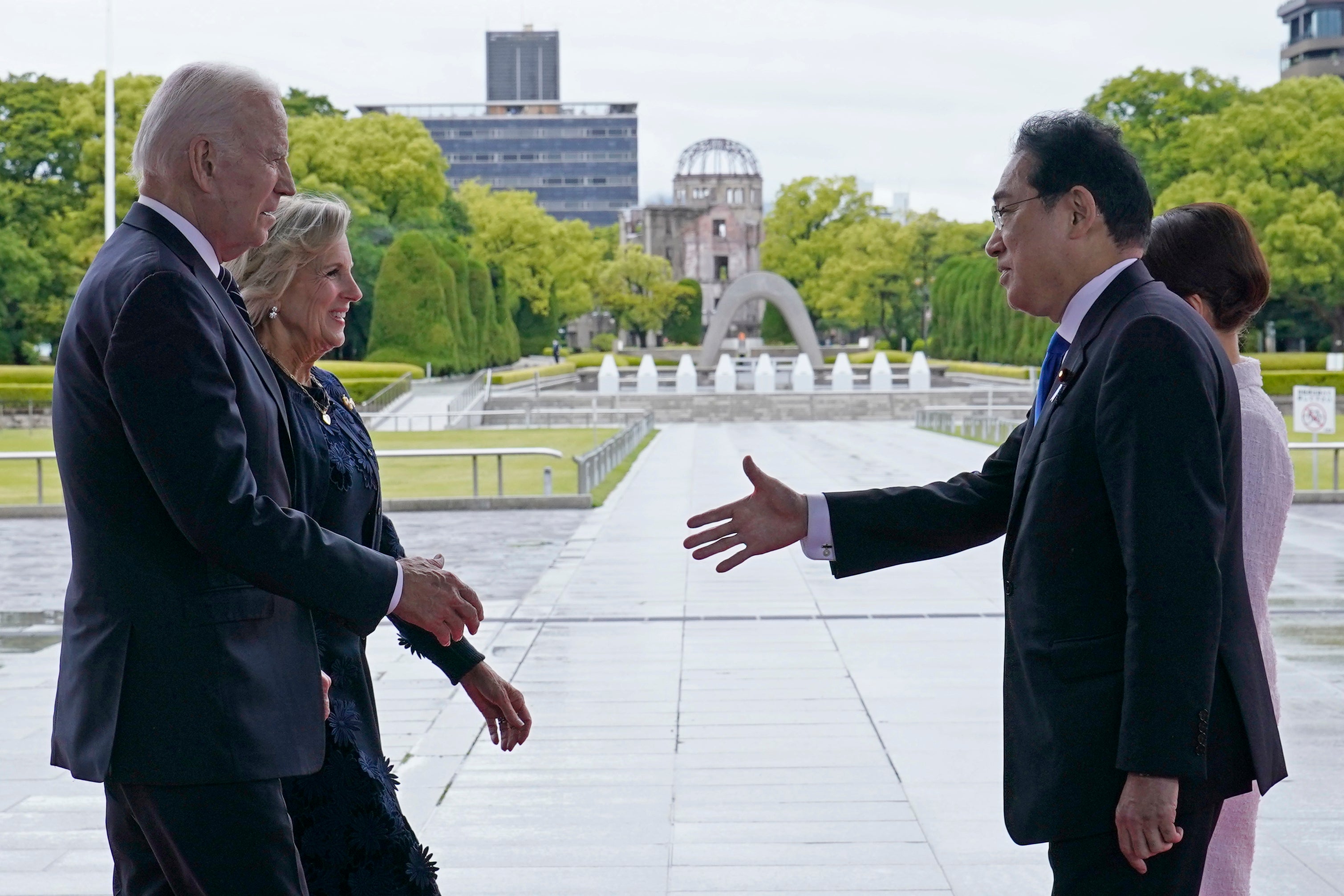

As leaders of the world’s seven wealthiest nations gathered under Japan’s leadership to tackle the most pressing issues of our times, they face a critical test of their commitment to combat the climate crisis.

The leaders on Friday will be convening in historic Hiroshima, where the devastating power of nuclear weapons was unleashed.

G7 leaders from the US, UK, Japan, Germany, France, Canada and Italy face a critical decision: prioritise the shift to clean energy or continue down the destructive path of fossil fuel dependence.

And current signs are already discouraging, said several climate experts.

Last month, the G7 climate ministers stated they are “steadfast in their commitment to keeping a limit of 1.5C global temperature rise within reach”. But this commitment has not yet been followed by tangible action.

Despite dire warnings this year, the G7’s focus is “heavily on a 2050 plan rather than meeting 2030 targets”, activists say.

“The G7 is a test for Japanese leadership,” says Mary Robinson, chair of the advocacy group The Elders.

“There is not in Japan a sense of urgency that I see in most developing countries and in European countries that I see now and the parts of the US that are not in some sort of political denial”.

Ms Robinson says there is a “need to ensure Japan gives leadership on the climate crisis as a crisis so we can have a decision better than the minister’s decision, which was a holding decision in my view.”

International gatherings like the G7 have often been criticised for delaying meaningful climate action as countries tend to prioritise short-term economic gains over pressing crises.

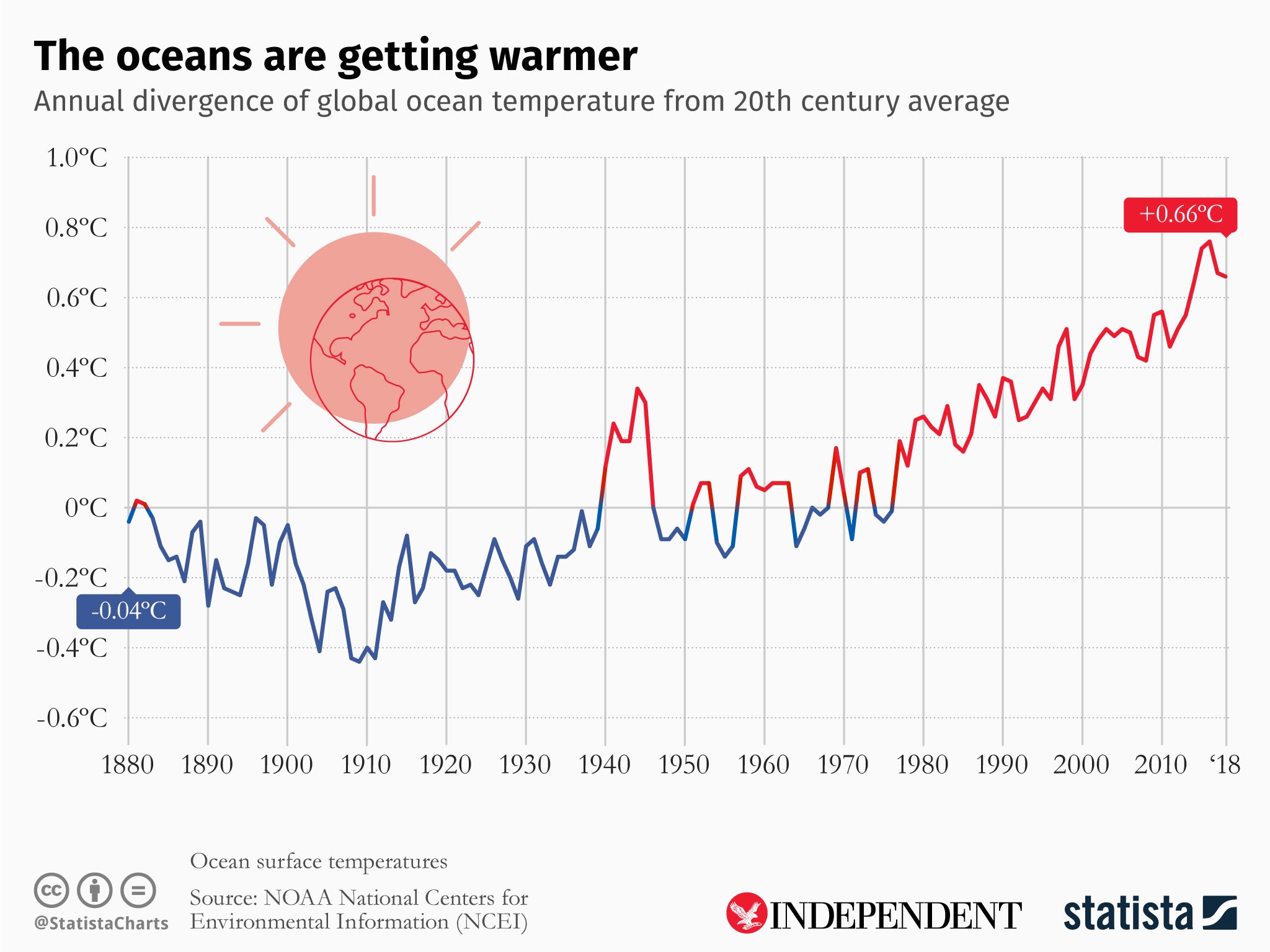

To add to that, there has been an inundation of catastrophic warnings this year about the climate.

A recent report by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) paints a dire picture, revealing the world to be on track to surpass the 1.5C target of the Paris Agreement within the next five years.

While the warming may be influenced by the El Niño weather phenomenon, scientific consensus points to severe and far-reaching future impacts.

To date, the world has already experienced a temperature increase of 1.2C compared to pre-industrial levels, primarily due to greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel usage.

The consequences have been devastating, including more frequent and intense heatwaves, melting of Antarctic ice and devastating wildfires and floods.

This year alone, countries across Asia, southern Europe and northern Africa have suffered deadly heatwaves that claimed lives and caused significant economic losses.

The choices made at the G7 summit will also serve as crucial motivation for upcoming events like the G20 summit in India and the UN’s 28th Conference of Parties (Cop28) in Dubai.

“We are at a very urgent moment,” says Alden Meyer, senior associate at climate advocacy and research organisation E3G. “We have wasted 30 years since the Rio Summit trying to come to grips with this climate emergency, and we’re really down to our last chance.”

Wealthier nations also need to address the requirement of more finance for developing and under-developed countries, including doubling adaptation funds aimed at helping vulnerable countries cope with climate change and how to populate the new Loss and Damage fund established in Sharm el Sheikh last year.

Most wealthy nations have failed to meet their finance commitments so far. Experts say the statements from G7 are also not very uplifting.

“It’s not about billions, it’s trillions,” says Sima Kammourieh, E3G’s senior policy adviser.

“There will be no transition without the money. The money needs to be moving to the right places at the right scale,” she says, explaining the inclusion of public finance for lower- and middle-income countries.

“Unfortunately, what we saw coming out of the finance ministers was a real letdown.”

While there has been an increase in initiatives to help developing countries move away from coal, experts say more also needs to be done to tackle the debt crisis in climate-vulnerable countries.

“This question of how do we avoid default in countries that are having climate distress needs to be addressed at the top of the agenda at the G7 and I have not heard any very good suggestions,” says Amy Jaffe, a senior fellow at Tufts University’s Fletcher School.

“We need to have a sort of a grander vision for how we’re going to intervene, whether that’s debt for climate swaps, and making that a more active part of the policy.”

Paving the way ahead for decarbonisation also includes refraining from new gas investments and fulfilling the pledge to end international fossil fuel finance.

Gas remains a point of contention in international negotiations. At Cop27, developing countries like India and China raised objections to singling out coal as developed nations continue to use gas as a transition fuel.

“The temporary argument of the Russian war does not justify any longer gas investments that are not in line with 1.5C and risk lock-in effects,” says Christoph Bals, policy director at non-profit Germanwatch.

Meanwhile, Japan’s own record of dependence on fossil fuels has become a discouraging sight.

Its goal of sourcing 36-38 per cent of its electricity from renewable energy sources by 2030 falls short compared to targets set by other G7 countries. Canada, Germany, the UK and Italy have already achieved higher renewable energy ratios than Japan’s 2030 target.

The G7 is a test for Japanese leadership.

In 2022, Japan sourced the smallest proportion, 29 per cent, of its electricity from clean sources, with fossil fuels still accounting for a staggering 71 per cent. Additionally, it has the highest share at 33 per cent of coal generation in the G7.

Climate research organisation Ember released a report highlighting Japan’s underutilised wind energy potential.

Despite its considerable capacity, wind energy only accounted for 1 per cent of Japan’s energy mix in 2022, while other G7 nations achieved an 11 per cent share.

Experts say the final G7 statement must clearly state how they intend to keep the 1.5C limit alive and include stronger commitments on climate finance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks