How does it feel to be shortlisted for the Booker prize?

The shortlist for the UK’s most prestigious literary award was announced this week – but is it stressful for the nominated authors? Charlotte Cripps investigates

The Booker Prize is like the Oscars for literature but how do authors feel about being shortlisted – or even winning?

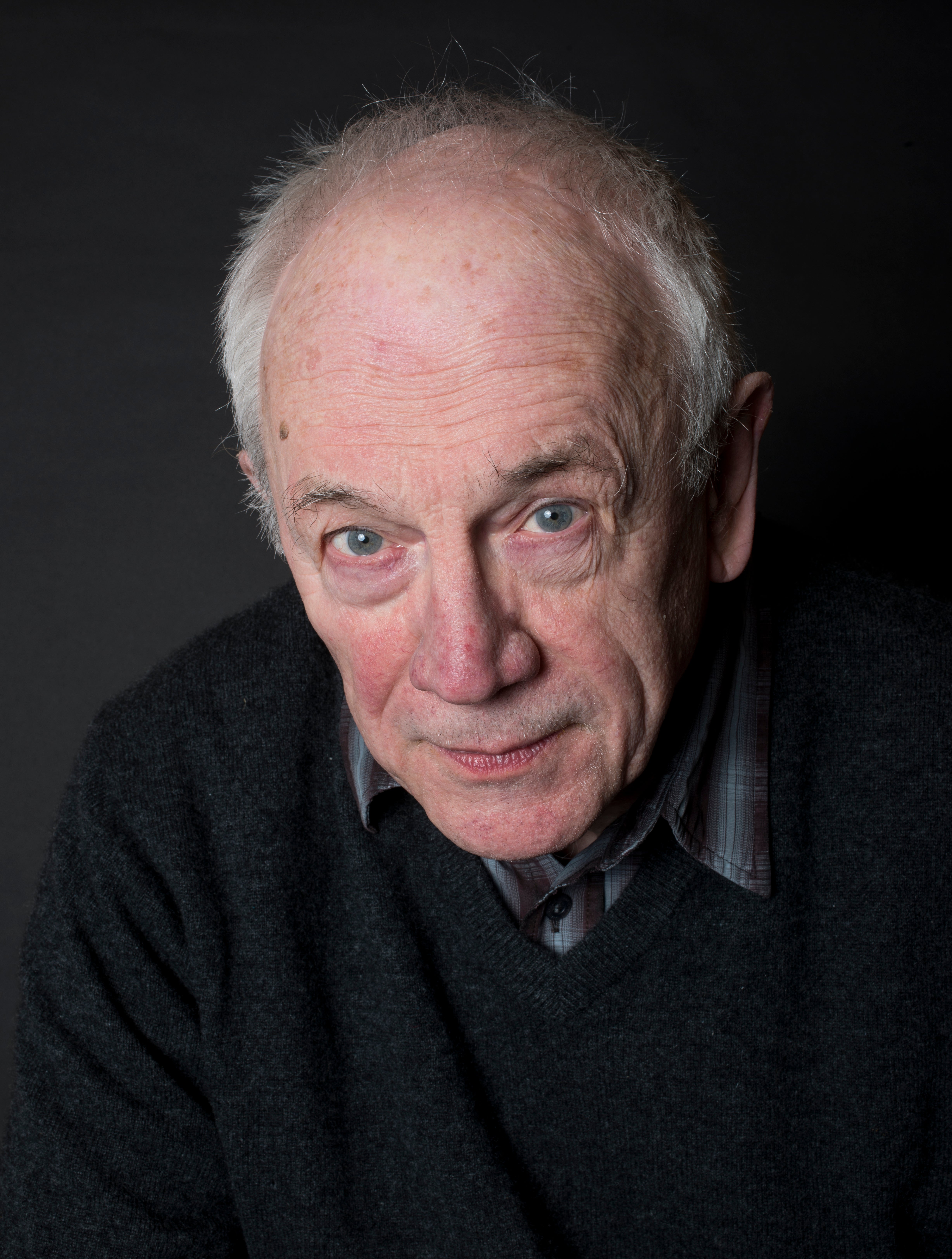

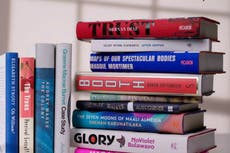

This year’s six Booker Prize shortlisted authors were announced on Tuesday evening by the Chair of Judges, Neil MacGregor. They include Alan Garner, 88, with Treacle Walker – he’s the oldest author ever to be shortlisted – and Claire Keegan with Small Things Like These, which at 116 pages is the shortest book (by page number) to be recognised in the prize’s history.

Being shortlisted may not be as life-changing as winning the prize itself, but it certainly ups the game. It’s a label that sticks and although book sales aren’t anything like as enormous as they are if they go on to win – the 2021 winner Damon Galgut’s The Promise sold almost 2,000 per cent more in the two weeks after the prize than it had done before it – it’s still significant.

Galgut tells me that winning the prize is “thrilling and numbing. Unreal and terrifying. I’m still coming to terms with it”. Whereas the shortlist is a “boon and a blessing” and “a good place to be”.

“You feel noticed, but not too much. People see you differently (ie take you more seriously), which is hard to argue with,” he says.

When the Booker Prize winner is announced on 17 October in a ceremony held at London’s Roundhouse, it will be nerve-wracking for the six shortlisted authors – also including NoViolet Bulawayo with Glory, Percival Everett with The Trees, Shehan Karunatilaka with The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, and Elizabeth Strout with Oh William!

“It’s horrible for the six shortlisted authors – unbearable,” says Gaby Wood, the Director of the Booker Prize Foundation.

“They have to sit through dinner and wait and see. One year I passed an author at dinner and asked him ‘are you alright?’. He said, ‘yes, can you tell us when we are going to be put out of our misery?’”

She adds: “We try and invite the previous shortlisted nominees to the dinner just so they can enjoy their meal because in the year they were shortlisted it must have been impossible.”

This year’s shortlist was made from 169 novels published between October 2021 and September 2022. The Booker Prize is open to works by writers of any nationality, written in English and published in the UK or Ireland. It’s an arduous task for the five judges who read all the novels over seven months from January to July – “it’s about one day,” says Wood, before they whittle it down to “The Booker Dozen” of 12 or 13 novels.

In 1994, the Booker judge Julia Neuberger pronounced Scotland’s first Booker Prize winner James Kelman’s novel ‘How Late It Was, How Late’, ‘a disgrace’

The judges met late last week in a private member’s club in Soho to agree on the shortlist – the Booker Prize is a charity and still has no office despite its prestigious reputation. By then, they’ve re-read all the 13 longlisted novels and come “armed with a sense of how those 13 books stand up to second reading” explains Wood. “Often the books become richer, sometimes poorer.”

It’s a full-on day of discussions. On MacGregor’s suggestion, this year each judge sent their top six to Wood in advance “so there was no prejudice – no one could influence anyone else”, says Wood.

“Do any of them rise to the top? Do any of them sink to the bottom? Normally during a process like that, some of them will fall away. But when I got the lists back, every single one of 13 longlisted books were represented in those votes.”

At that point, they knew the meeting would be really long. “We thought that the judges would be really distressed to lose the books that they loved. That often happens – it can really painful. You’ve championed a story for so long and you can’t bear to see it go. But that didn’t happen.”

To help them, the judges this year also physically moved the 13 novels around a table to slot the shortlist into place until they all agreed on the final six.

“Everybody had a go at arranging the books and they all came to a decision that they were happy with.” There was no bloodbath – although it remains to be seen how things go when deciding the winner next month.

Luckily, the shortlisted and winning authors are blissfully unaware of what goes on behind the scenes – most of the time.

The Booker isn’t without its scandals. In 2019, judges couldn’t agree on a winner and flouted the rules by announcing joint winners – Bernardine Evaristo with Girl, Woman, Other and Margaret Atwood, who had won it in 2000 for The Blind Assassin, for her new book The Testaments. In 1977, the poet Philip Larkin, who was the Booker Prize Chair of Judges that year, threatened to jump out of the window if Paul Scott’s Staying On didn’t win. Scott’s book did win – although sadly the author died of cancer six months later aged 57.

In 1994, the Booker judge Julia Neuberger pronounced Scotland’s first Booker Prize winner James Kelman’s novel How Late It Was, How Late, “a disgrace”.

Wood, who now oversees the prize and has chosen the judges since 2016, was also a judge herself in 2011, when the prize – chaired by Stella Rimington – was heavily criticised for “dumbing down” the Booker.

“A couple of judges had said they were looking for readable books – or novels that zipped along. That was not seen to be a good thing,” says Wood. “In practice, Julian Barnes won [with The Sense of Ending] and I don’t think there was anything dumb about that. It was not a popular year on the outside – but that was my year.”

While most people think the Booker Prize is about the glory, or the cash prize of £50,000 (or £2,500 for each shortlisted author) – and of course increased book sales – its main aim is to foster a love of reading.

“It doesn’t actually make any money. From our point of view, the Booker Prize Foundation is a charity with a purpose to promote the love of literature for the public benefit.”

But for the authors, the prize brings its own pressures – as well as ups and downs. “At least the whole next year is spent talking about your book or having won the Booker. There is so much demand on writers at that point,” says Wood.

“It’s either that they don’t particularly feel comfortable with the public life or that they want to get on with their own writing and want to leave that book behind. By the time a book wins the Booker, it’s at least a year since they finished it. Or there could be a lot of pressure to write the next book. Everybody feels it differently. And then some people, who are further along in their careers, are really happy. I think the £50,000 is the least of it to be honest – it’s not only the increased sales that are so astronomical, but the book deals with publishers all over the world for the rest of their career.”

It’s not always rosy to get on the shortlist. The two-time Booker winner Hilary Mantel – a favourite to win in 2020 with the third novel in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, The Mirror and the Light, spoke to the Sydney Morning Herald about not making it onto the shortlist that year. “Although disappointing on one level it was quite freeing on one level,” she said.

It’s understandable. Galgut who like many writers “usually likes spending lots of time on his own,” says that has “become almost impossible”. “I’m known as somebody who doesn’t talk a great deal, and that’s had to change too. Essentially, life has become very public and very noisy. I’ve been negotiating that one day at a time, and there have been moments when that feels overwhelming. But of course, there are profound pleasures along the way. And there will, presumably, be an end to the noise.”

The Promise was his ninth novel – does he feel he’s made it now or does he want to win it again?

“Nobody with serious intentions writes a book with the aim of winning a prize. So the idea of ‘making it’ doesn’t really feature. It’s a fabulous acknowledgement, but the writerly part of me is longing for the space and silence to get back to work. Soon, I hope.”

Winning prizes, he says, doesn’t change the creative process either. “I’ve always found it very hard to write and that hasn’t become easier – or more difficult. In a certain sense, prizes and accolades happen on a different planet to the work itself, which is really a struggle with yourself.”

For the 2019 Booker Prize-winning Evaristo, winning has been nothing but positive.

“It was and still is an amazing experience. I started publishing books in 1994 and it was always a struggle to get attention and break through onto the main stage. When I won the Booker, I arrived in the spotlight and my career was transformed in every way imaginable for the better,” she says.

When I started out, at three minutes past four on Tuesday, 4 September 1956, the first Booker Prize was 13 years in the future

“I have a solid foundation as a person, a writer and in a creative practice rooted in 40 years working professionally in the arts. My thematic and stylistic compulsions as a writer have not changed. I’ve learned that I can only do my own thing because if I try to write to the perceived expectations of others, I lose my connection to my creativity.”

For most of the shortlisted authors this year, it’s a new experience – apart from Zimbabwean author Bulawayo who is on the shortlist a second time with Glory, having also made the list in 2013 with We Need New Names. What was Bulawayo’s reaction this time to being shortlisted?

“I celebrated the news with my amazing team, including my incredible editors, called one of my sisters, who said, ‘well, I guess I have to read the book.’ I must say I love my family in times like these.”

How does she deal well with being in the spotlight as an author? Writers are notoriously reclusive. “I do what I can, but I’d really rather be creating and leave the book to speak for itself,” she says.

What is more exciting than the cash prize is “the readers I may not have otherwise reached, the conversations that Glory may inspire,” says Bulawayo.

For the octogenarian, Garner, being shortlisted for the Booker Prize was not always on the cards. “When I started out, at three minutes past four on Tuesday, 4 September 1956, the first Booker Prize was 13 years in the future,” he tells me.

Is it nerve-wracking waiting to hear if you made it onto the shortlist? What were you thinking as you waited?

“Writing a book is what wracks the nerves. I was planning the next while I waited.” But what was his reaction to being shortlisted? What was the first thing he did?

“The first thing I felt was delight, on behalf of the book’s achievement and of all the people that have supported me through the 62 years of being published, so far. The first thing I did was to go to bed and sleep.”

If he wins the Booker, Garner, says he would use the Booker Prize cash win of £50,000 to “continue to survive and to write, and to look after the ancient house that has looked after me for the past 65 years”.

Keegan – who was shortlisted this year for Small Things Like These – says nothing about being nominated worries her in the least.

“I’ve nothing to lose and don’t see how the shortlisting could in any way hinder my future work or writing. It’s a huge honour, simply.” After the news was announced, Keegan walked to the shop to get some milk and returned home to “over a hundred messages/emails had come in on the phone”. “Some of my students were in tears. Others sent photos of themselves with champagne. Still others sent screenshots of the announcement on the 9 o’clock news.”

For her, It wasn’t nerve-wracking waiting for the shortlist announcement, she says. “During August, I was just getting on with life. My mother passed away last month so I’ve been grieving her memory and clearing out her house on and off ever since. It’s been a bittersweet time for I know she would have been very proud to have seen my novel being shortlisted for the Booker Prize. I’ve found all kinds of newspaper cuttings here about my work over the years. She was a great reader and I’m sure that some of my storytelling abilities came down through her.”

What would Keegan do with the £50,000 Booker Prize if she won? “Must we talk about money?,” she says. “In many ways, this book is an anti-money novel, a book about someone who chooses the moral right over personal gain. Of course, I’m grateful (as I’m sure all the shortlisted are) to those who have sponsored this year’s Booker Prize. It’s a hugely generous award but I’m already grateful to them for the £2,500 prize I’ll be awarded – which will most likely go towards replacing my 19-year-old jeep. I have to laugh now as Bill, the central character in Small Things Like These, drives a lorry which is giving out and failing on him in the end!”

Wood says that “the prize is so well known – the recognisability and the prestige is so high” when she saw Galgut after he’d won last year – she almost felt like apologising. “Obviously he’s gone round the world touring with this book and it’s exhausting. This is what happens to people – they can’t write anything for a whole year after winning the Booker Prize. And he said: ‘It’s ok. It’s all for a good cause.’ And I said, ‘what your book?’ And he said ‘no, reading.’”

What advice would a Booker winner give a struggling author who wants to win the Booker one day?

“Focus on developing your craft and reading widely and deeply, and not on winning prizes,” says Evaristo. “They can be a useful and even a career-changing by-product but they should never be the purpose of writing. Writing to win prizes lacks creative integrity and is a waste of energy. Who can predict jury decisions?” Galgut adds: “Seriously? There’s no advice that will help you win anything, except the injunction to write as well as you can. Leaving the Booker out of it, my advice to struggling authors is to keep on struggling. It’s the only way to get a little better at what we do.”

The Booker Prize 2022 is announced on 17 October. www.thebookerprizes.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks