‘Neuromarketing’ claims to make us shop but is it a decent thing to do?

By bypassing the brain’s processors and dealing directly with the subconscious, ‘Neuromarketing’ could be prodding us into new purchases. In a new book, James Garvey questions the practitioners’ ethics

Functional magnetic resonance imaging scans tell you which part of the brain is active; and if you also know something about which bits are associated with which mental functions – such as memory, perception, pleasure and pain, judgement, emotion and planning – then you can begin to make educated guesses about what a person is thinking and feeling when exposed to products, packaging, advertising messages and web pages.

This is the hope held out by practitioners of neuromarketing. It's suggested by some that fMRI scans can spot mental activity below the threshold of conscious awareness, revealing facts about our minds that have effects on what we think and feel and do but that are introspectively unavailable to us. By understanding and finding ways to affect these subconscious processes, it's possible that persuasive messages – if it's still right to call them that – can bypass whatever conscious defences we might have and influence us without our knowledge.

In a seminal paper published in 2004, researchers performed a variation of the “Pepsi challenge” on subjects in an fMRI scanner and discovered what many take to be the neural correlates of the mighty effects of brand power, getting them attention in marketing circles and beyond. For the researchers found that different parts of the brain were active in the anonymous trials and in the branded trials.

When all subjects had to go on was an anonymous taste, a part of the prefrontal cortex was active, the bit associated with appetite and reward. But when subjects knew it was Coke, different parts of the brain swung into action – the parts associated with memory, emotion, thinking, judging and, the authors speculate, “recalling cultural information that biases preference judgements”. So, taste a sugary brown liquid and part of your brain reacts to the taste. Drink a Coke, however, and the experience is enhanced, processed by different parts of your brain, and transformed by brand messaging, by everything you have been made to think and feel about Coke. The commercial application of this kind of information was not lost on those in the business of branding and selling.

In 2001, there were just two firms billing themselves as experts in the techniques of what is now called “neuromarketing” (the word only appeared in 2002). There are now more than 300, alongside departments in more traditional research companies. There are even university degrees in the subject.

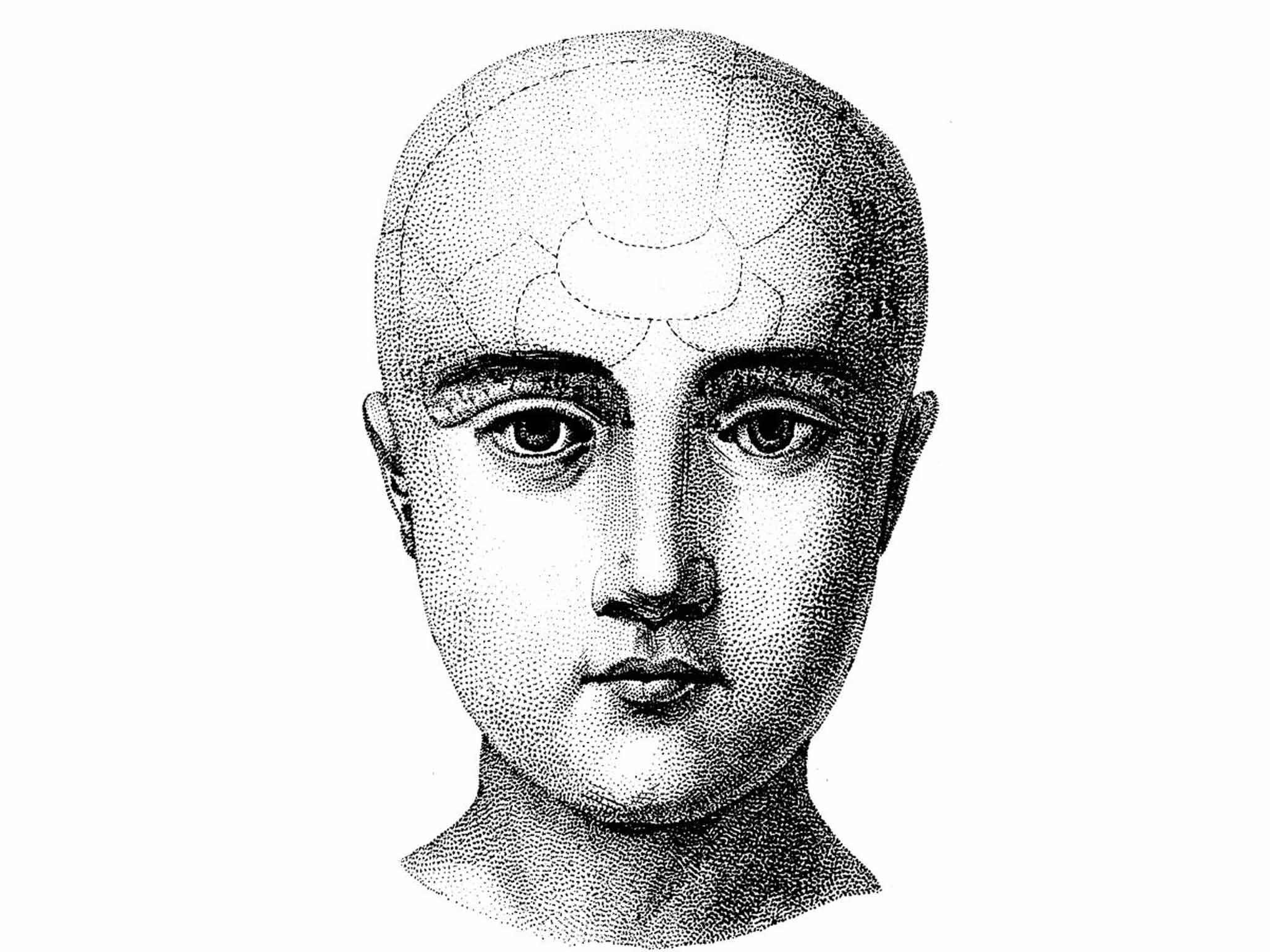

Neuromarketers make use of much more than just fMRI technology: electroencephalography (EEG), for example, which measures and records electrical activity on the scalp. Different electrical frequencies appearing in different places on the head are thought to be associated with particular mental events.

But while an fMRI scan requires a subject to remain motionless, flat on their back in a large machine, an EEG can operate on someone who is moving around, inconvenienced only by the wearing of a shower cap of electrodes. These can be worn while shopping, most of the machine slung in a backpack, with the results recorded in real time and weighed microsecond by microsecond against a subject's every move.

This is thought to be particularly useful information when synchronised with the results of eye-tracking devices – because what you are thinking and feeling can be correlated with what you are looking at. Such devices measure where and how long the eye fixates and how it moves between fixation points, resulting in “scan paths” or “gaze plots” that show exactly how the eye travels over, say, a magazine advert, television commercial, website, aisle, package or shop front. Data from individual plots can be combined into “heat maps”, representing where the visual action is by lighting up hotspots with red, indicating a lot of interest, down to blue for much less.

More information about pupil dilation and blink rate – both associated with attention and arousal – can be gathered at the same time by more sophisticated machines. And yet more can be discovered by monitoring the mostly automatic, purely biological responses to what we sense around us – responses that are closely associated with emotion. Finger-pulse meters and blood-pressure monitors can detect changes to the heart. Saliva swabs can determine quantities of cortisol, a steroid present when we experience stress. Facial electromyography can monitor the almost-undetectable electrical impulses associated with contraction of the facial muscles (thought to indicate both conscious and unconscious emotional reactions). The electrical conductance of the skin varies according to how much sweat we produce, and this too can be measured to gauge our emotions.

But how is all of this information actually used? There's a lot of variation among practitioners. Some focus on the brute elements of perception – but not all their results are predictable or easy to explain. For example, something as basic as colour and lighting can have unexpected effects on our shopping. Shops decked out in blues and green are experienced as relaxing; but where orange dominates, customers feel stimulated. A lot of red and yellowish-green result in negative emotions and the desire to leave a shop. Dark colours can make us feel aggressive.

Curiously, printing bargain messages in red can make men believe they “will save a lot of money”, but the effect vanishes if they think carefully about the offer – and for what it's worth, women seem largely unaffected by the colour of sales messages. The effects of store lighting, on the other hand, are so pronounced that researchers “found it was possible to control the time customers spent examining products and the number of items they looked at purely by adjusting the level of brightness”. Dim lighting mellows us and makes us feel relaxed enough to browse, but in general bright lights intensify our interest and lead to higher sales.

What we hear affects us too, and this is largely determined by shops' choice of background music. (It's often carefully made, and professional music profilers are on hand to help.) One study showed baby boomers were more likely to make purchases with classic rock in the background, even though, when asked a bit later, two-thirds couldn't remember what was playing. Slow-tempo muzak can slow shoppers down, increasing time spent shopping and thus boosting sales. And our purchases can be manipulated by music, too. When a wine store switched from Top 40 to classical, people spent more buying more expensive wines. As for jingles and the mood music for commercial messages, neuromarketers claim they can identify the jingles most likely to stick in our heads and the music most likely to affect our emotions.

Even touch can affect our financial decisions. Researchers believe particular sorts of physical contact can increase our tendency to take risks – the idea being that, from an early age, we associate a gentle touch with comfort and security – and some researchers have found that even an unobtrusive brush of the hand when you receive your change can make you feel more positive about both your purchases and the shop.

Other neuromarketers are moved by thoughts about a dual-systems approach to the mind: fast, automatic, intuitive thinking (system 1) versus slow, reflective, rational thinking (system 2). The hope is that system 1 might be prodded in subtle ways, increasing the perceived value of a product, which in turn might influence our purchasing decisions.

In a study led by the neuroscientist Brian Knutson, subjects were shown images of products, followed by prices, and were then asked to press a button if they thought they would buy at that price – their neural activity analysed all the while using fMRI. Knutson found some images of products activated the brain's “reward system” and, just as in the Pepsi challenge, brand value seemed entwined with how positive subjects felt. But when prices were shown, the parts of the brain that process pain kicked in. So the trick, it would seem, is finding ways to tip the balance: if the gain outweighs the loss, we seem inclined to make the purchase.

All this leads to a marketing strategy – increase reward and, at the same time, decrease pain – which can be done explicitly and a little clumsily by lowering the price or increasing the reward (say, by adding more product). But neuromarketing holds out the possibility of doing something else entirely: making subtle changes to the appearance of both the product and the price that can alter our perception of value and pain. They maintain that while decision-making sometimes happens explicitly – out in the open, consciously, under the gaze of system 2 – the unconscious processing done by system 1 has a much greater effect on our choices than we realise and therefore gives the neuromarketer far more opportunities to change our minds.

According to American neuromarketing expert Phil Barden, our automatic system picks up on almost everything, so even the subtlest cues can make a difference to perceived reward and pain. “The autopilot processes every single bit of information that is perceived by our senses – 11 million bits per second, roughly the size of an old floppy disk – no matter whether we're aware of this input or not,” he says. “And every input is processed by the autopilot and can potentially influence our behaviour.”

This processing capacity is contrasted with the 40 bits our working memory can handle, a rough guestimate of the limits of our deliberative system 2. “Even if we wanted to decide reflectively, our limited capacity constrains us from doing so,” Barden says. What's more, there's not much room for manoeuvre when it comes to explicit value – all drain cleaners clean drains – so the action is mostly at the implicit, or hidden, level. That's where perceived value can be added, and where the perceived pain of price can be minimised. Consider value first.

The reward centres of the brain might well be affected by creating a large number of positive associations with the brand in question through advertising. If the brand is strong and its advertising has done its work, this creates positive undercurrents in our neural networks, triggering more action in our reward centres, outweighing the pain of parting with money and finally shifting us into buying behaviour. It's partly why we might be willing to pay £3 for a single cup of Starbucks' coffee and the same amount for an entire bag of ground coffee that can brew 30 perfectly decent cups. Implicit triggers overwhelm us, and system 2 never gets the chance to compare the reward we're actually getting for our money.

But value might be enhanced in other more sneaky ways. Barden's example is packaging specifically designed to set off subtle, subconscious cues: in this case, the persuasive symbols built into a shower gel bottle. By designing the container so its colour and shape are suggestive of motor-oil packaging, a number of cues get picked up by our all-seeing system 1 and pump up the perceived value of the stuff.

What's perhaps less obvious is the malleability of our perception of price. Perhaps prices were once set by plotting demand curves: the aim was to find one that most people were happy to pay but still resulted in a decent return. But now pricing consultancies offer all sorts of advice that has more to do with how our brains work than actual bottom lines.

A raft of studies show that we perceive £2.99 as a much better price than £3, and consultants may try to play on our in-built reaction to scarcity by using “limited time offers”, manipulate our natural tendency to discount the future with the suggestion that we could “buy now, pay later”, or use the power of reciprocity by offering us free gifts. But many other, less obvious factors influence our experience – and how price is presented is enough to change our perception of it.

Using restaurant menus, researchers tried several variations: an entirely numerical version with a pound sign (for example, £10.00), the same but without a sign (10.00), and a version with the price written out, using no numbers at all. People who saw the price without the pound sign spent more – it's thought it's processed by system 1 as a reliable pain signal. And by the same token, a price printed in black and white is perceived as more expensive than the same one presented with the words “discount price” on a blue background. The same number with the words “special price” against a red background seems like even more of a bargain.

However, what appears to have the biggest effect on our perception of price is context – and, in particular, contrast. We don't really know how much something is worth to us unless we have something to compare it to, and that something can be presented to us by those who wish to influence our experience of cost. The best example of this is an unusual offer made by The Economist magazine. Its website presented these options: an online subscription for £39; a print-only subscription for £90; and a print and online subscription, also for £90. But why would anyone go for print-only when you can have a print and an online for the same price?

It turns out that including the duff offer changes how we perceive the value of the other two options and pushes more people into making the more expensive choice. In a study offering 100 students the original three options and another 100 just two, 68 of the latter group choose the cheaper online subscription and 32 choose print and online. But if they also saw the print-only option, just 16 chose online only and 84 opted for the bigger offer.

Price consultants advocate the use of “decoys” such as this whenever products are difficult to compare. Say two competing phone-makers are each selling one phone, each with a range of different features: it's hard for us to work out what matters most. But if you're selling phone A, it makes sense to offer a decoy, phone A-minus, the same phone with, say, a slightly smaller memory and slightly higher price tag. If it's hard for consumers to compare two competing phones, it's easy to compare phones A and A-minus – and more people will end up buying phone A as a result. Decoys like this appear almost everywhere, from wine lists to car lots – all intended to sell something else.

So: how to deal with these manipulations? In the summer of 2011, France made this addition to its bioethics code: “Brain-imaging methods can be used only for medical or scientific research purposes or in the context of court expertise.” The move in effect bans the use of brain imaging for commercial purposes – and the worries voiced in France at the time can be heard in Anglophone discussions now.

Some argue that the claims of neuromarketing are overblown. Brain scans are said to have revealed that eating chocolate is better than kissing – according to an investigation underwritten by Cadbury's. Elsewhere, neuromarketing has disclosed the formula for the perfect holiday – this study was underwritten by Holiday Inn. As one sceptic observed, this is “little more than PR in an ill-fitting science suit”. But other objections start with the possibility that at least some neuroscience can reveal commercially useful facts. The question then is whether or not morally problematic manipulation is going on.

Almost none of the discussion around the “ethics of neuromarketing” on the part of practitioners concerns such moral questions. Instead, there's the promise that neuromarketers will not hoodwink their clients by exaggerating their ability to peer into our minds. There's no reflection on human dignity, the right to privacy or the value of human freedom.

So, to ask a plain question: is taking advantage of an understanding of the way a human mind works and using that to get us to pay more money for something a decent thing to do? Whether it is or not, it's something that happens to you and to me every day.

The Persuaders, by James Garvey (Icon, £12.99), is published on 4 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks