Why the days of student loans as we know them could be numbered

As Rachel Reeves digs in over forcing more graduates to begin repaying their student loans sooner at eye-wateringly high interest rates, she has put the government on a collision course with millions of voters. To make sense of it all, university guide expert Alastair McCall looks at how we got to a place where the poorest pay more than the richest – and how else the UK’s higher education bill could be settled

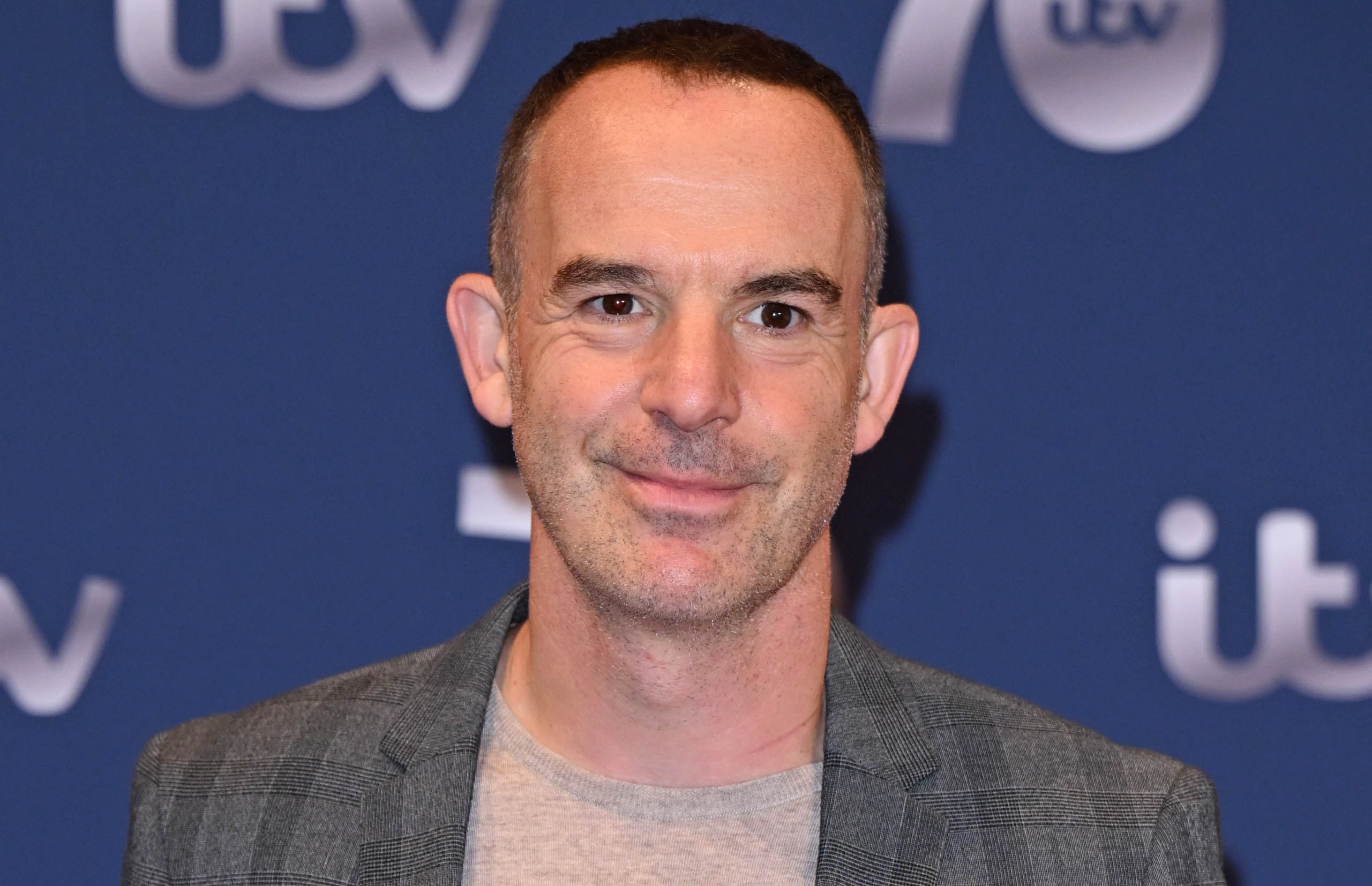

The days of the present student loan system may soon be over. It is hard not to come to that conclusion as the outcry continues surrounding the length and scale of repayments, and the excessive interest being charged on the debt, which has put consumer champion Martin Lewis on a collision course with Rachel Reeves.

As the chancellor doubled down in her defence of student loans, saying they were “fair and reasonable”, it was clear she had no concept of the psychological impact of giving up nine per cent of your salary above a soon-to-be-frozen threshold each month, only for most to see the debt mountain keep on growing.

Reeves might want to start listening to those who do, if only because of the potential impact the 5.8 million voters affected by the freezing of student loan repayment thresholds could have at the next general election, should they mobilise against the government in a significant way.

Lewis is asking graduates to write to their MP about how the government has breached its contractual terms regarding the loans. A YouGov poll last week showed that 44 per cent of the British public believe that some or all student debt should be written off, with a further 76 per cent saying they think the 6 per cent interest being paid is too high.

How did we get here?

Like many, I was once in favour of a university financing system that kept higher education free at the point of delivery. At a social event at Northumbria University shortly after the introduction of “plan 2” loans to coincide with £9,000-a-year tuition fees, I joked with David Willetts, then higher education minister, that he should market student loans as “the only loan you will ever take out that you might never have to repay”. I’m not laughing any longer.

I have skin in the game, having edited and compiled university guides for national newspapers since 1998, all of which have overwhelmingly encouraged sixth formers to progress into higher education. More recently, my three children have been going through or have recently exited the higher education system. Seeing their indebtedness – even after considerable parental financial support – has given me serious pause for thought.

It is hard to believe that our prime minister is the same Sir Keir Starmer who pledged to abolish tuition fees during his party leadership election campaign in 2020. And if we are a long way off those days, we are even further from the concept introduced in 1998 of students making a contribution towards the costs of their higher education in the form of a £1,000-a-year upfront fee.

The intervening years have seen Starmer’s pledge to abolish withdrawn, and the student contribution become the full nine yards. No wonder then that recent graduates are complaining about their level of debt, the rate of interest charged on it and the salary thresholds at which they begin to pay it off.

It is this toxic combination of complaints that now threatens the whole, scarcely fathomable structure we have for paying for higher education in England.

“I am amazed it has taken so long to kick off,” says Gavan Conlon, a partner at London Economics, the policy and economics consultancy that has undertaken considerable research into student loans. “This has been floating around for ages; maybe it reflects the difficulty in understanding the system.”

Doing the student loan maths

Thanks to savage interest rates, many graduates in England, who now have an average student loan debt of £53,000, are facing retrospective repayments of student loans that will amount to £100,000 or more, which they will still be making into their fifties and sixties.

This level of indebtedness might not be quite what prime minister Tony Blair envisaged when he defended in 2004 the proposed introduction of the first tuition fee loans of £3,000. “If we want to increase the numbers going to university still further, and we need extra money for universities that everyone accepts we do, it either comes exclusively from the taxpayer, from families, or by graduates repaying something after they graduate,” he said.

How much graduates pay depends on which plan they are on. There are significant variations in the terms with four undergraduate repayment schemes – plans 1, 2, 4 and 5 – currently active.

The government owns the vast majority of the student loan book, with only a small proportion (£7.4bn) of the £266.6bn incurred by students in England between 1998 and March 2025 sold off to private investors in 2017 and 2018.

So, it is the government that stands to benefit most from the controversial decision in last November’s budget to freeze the threshold – £29,385 – at which repayments begin for 5.8 million plan 2 student loans.

The thresholds had risen by the Retail Prices Index (RPI) inflation rate for both 2025-26 and 2026-27. When plan 2 loans were introduced in 2012, the repayment threshold was £21,000. To take account of cumulative inflation since then, the threshold should already be £30,600. Instead, it will still be more than £1,200 shy of that in four years.

For those plan 2 students who began their degrees between 2012 and 2022, nine per cent of all earnings above this level will be put towards student loan repayment. So, a graduate earning £30,000 a year will pay £55.35 off their student loan debt over a year, rising to £505.35 for those earning £35,000, and £955.35 on a £40,000 annual salary. For every £5,000 increase in annual salary, graduates pay an additional £450 a year off their student loan.

Reeves sees nothing wrong in applying the same fiscal drag tactics on student loan repayments as she is using on headline income tax thresholds. In one interview, she went as far as to tie the row into bringing down NHS waiting lists. “To be able to bring down NHS waiting lists … that does require putting money in. So, my job is to get the balance right between tax and spending, and I do believe those measures [freezing loan repayment thresholds] are fair and proportionate,” she said.

Many others, including Lewis, have cried foul. “The British are traditionally not a very riot-y people,” says Conlon, “but imagine if HSBC changed the fixed rate they locked in three years ago at 2 per cent, saying you are now paying 4 per cent because we don’t like 2 per cent. People would be out in the streets.”

We are not quite at that stage, but Reeves is coming under mounting pressure to reconsider the freezing of the plan 2 repayment threshold at the very least.

And that pressure is triggered in part by a second student loan whammy: interest rates. Lewis is reasonably relaxed about the interest charged on student loans, as the debt is ultimately wiped out 30 or 40 years after graduation, regardless of whether the debt has been paid off. “For most people, the amount you owe is irrelevant,” he says on his moneysavingexpert.com website.

However, graduates are far less relaxed as millions will be deprived of 9 per cent of their income above the repayment threshold for several years longer than they might have been had interest on their student debt been lower – impacting everything from the mortgage they can afford to pay, to the supermarket they can afford to shop in and the holidays they can afford to go on. All of which affects the wider picture of the health of our economy and the much-needed growth which has so far eluded Reeves.

The squeezed middle

At the moment, the maximum 6.2 per cent interest (RPI + 3 per cent) charged to plan 2 graduates earning more than £52,195 means you have to earn more than £65,000 a year simply to outrun the accruing interest on the average student debt in England of £53,000 and begin to pay down the capital sum.

This means inevitably lower and middle earners will pay more than higher earners for their degrees. Our teachers and nurses potentially pay more for their university years than those who go on to be bankers and accountants.

It is another example of the “squeezed middle” bankrolling everyone else, and Rachel Reeves’s freezing of repayment thresholds will only pull in more of that group of plan 2 middle earners to pay student loans off for the full 30-year term.

Lewis’s own ready reckoner calculates that graduates who start work on a salary of £60,000 will pay back around £80,000 to clear a student loan of £50,000 over 16 years, while those starting on £40,000 will pay back more than £100,000 over 30 years without ever fully clearing it.

My two sons are among the plan 2 cohort. The eldest graduated in summer 2023, having borrowed £46,884 over the course of his degree. That debt has grown by 26.4 per cent – or just under £12,400 – to stand at £59,245 this week. At one point, interest was accruing at more than £360 per month with rates as high as 8 per cent shortly after he graduated.

Because interest is charged from the first day after the first payment is made to a student when they begin their degree – another iniquitous aspect of the current system – students leave university already owing vastly more than they have borrowed.

His younger brother left university last summer, having borrowed £55,029 in tuition and maintenance loans. Three months before his first repayment is even due, his debt is already 17.6 per cent higher than that, standing at £64,698 this week.

It is numbers like these that make the present system feel unfair. The level of interest charges – which on plan 2 at least have been running at well above the likely rate at which the government borrowed the money in the first place – will guarantee for many that the maximum 30-year term will be paid on their loan without ever fully paying it off.

And the more recent plan 5 plan is no better. My daughter will be a plan 5 graduate when she leaves university in 2028, part of the cohort that started their degrees after 1 August 2023. They benefit from lower interest rates, currently capped at RPI of 3.2 per cent (rather than 6.2 per cent for plan 2), but they begin making payments on salaries above £25,000 and have to pay for up to 40 years, which will take many to within a whisker of retirement.

“Plan 5 is deeply regressive,” says Conlon. “If you wanted to design a system that disadvantages low- to middle-income earners – predominantly women – you would design a plan 5 loan.”

There is, of course, a cohort of students for whom the present debate over thresholds and interest rates is completely irrelevant. Those from wealthy families can leave with no student tuition fee or maintenance debts at all. Parents who can afford private school fees might actually find that funding university for their children is slightly cheaper than the school years.

Data from four years from 2018-19 to 2021-22 shows that almost one in 10 eligible students did not take out a maintenance loan, while one in 20 did not take a tuition fee loan at all.

At the highest ranking universities attended by larger numbers of privately educated students, the proportion of debt-free graduates is even higher. A recent freedom of information request by the Durham University student newspaper, Palatinate, showed that one in five eligible Durham students did not take out a tuition fee loan.

What are the alternatives?

It would be wrong to say that there are simple solutions to the present student finance mess. Overall, student loan debt includes both tuition fee loans (currently £28,605 for a three-year degree) and maintenance loans to cover the cost of accommodation, food, books and socialising. So, any settlement is about more than simply paying off universities for their teaching services.

Calls to write off all existing student debt – £266.6bn as of March 2025 – are likely to fall on stony ground; the sum is not far short of our annual welfare budget (£333bn) and more than the annual costs of the health and social care (£202.5bn). Reeves has said explicitly that she does not believe the 50 per cent of the population who don’t go to university should pay (through taxation) for the 50 per cent of the population who do.

However, in other European countries, there is no aversion to the state largely picking up the tab for something seen to be of national benefit. In Germany, tuition fees in public universities owned and operated by the state were abolished in 2014. Students pay only a semester fee of between €100 and €400 for each of the six semesters of studying needed for most undergraduate degrees. In France, it costs students at public universities €178 per year for a bachelor’s degree, with the state picking up most of the estimated €11,000 cost of a typical degree.

In England, Conlon believes a “Step Up, Step Down” repayment system could offer a solution that does not see middle-income earners pay the most, keeping high earners repaying for longer by cutting the repayment rates as earnings rise.

So, for example, 3 per cent of earnings between £15,000 and £30,000 could be deducted for the lowest earners, rising to 6 per cent on earnings between £30,000 and £45,000, and dropping back to 3 per cent on earnings above £45,000.

Another idea would be to move to a system based around a graduate tax, which also has a strong appeal for its ability to ensure those who financially benefit the most pay the most. It would remove at a stroke much of the resentment and sense of unfairness surrounding the present system.

“Repayments should be based on the benefits of higher education and not on the costs. Individuals who generate greater benefits from their higher education should contribute more,” says Conlon.

Conlon suggests a graduate tax rate of perhaps 1.5-2 per cent could generate the necessary revenues. It must be recognised, however, that any change to the mechanism by which higher education is funded would require additional significant short-term subsidy from government during the transition period.

However, without such root and branch reform, how many repayment plans will we end up with – plan 10, plan 57? – as successive chancellors try to keep the burden of paying for higher education in England firmly on the shoulders of the graduates?

Prof Jane Harrington, vice-chancellor of the University of Greenwich, believes that the funding of higher education should be split more equitably.

“The cost of university should be split between the state, students and employers – as employers benefit from higher education as well.”

Greenwich is one of the institutions that has flourished with an increasingly socially diverse student body, triggered by the expansion of numbers in higher education over the past 30 years. “Putting the burden on just one group is hard to justify. We risk putting off the very people who ought to be benefiting from higher education.”

A perfect storm could be brewing. The unwritten contract behind high tuition fees (which are rising annually by RPI once more, unlike student loan repayment thresholds) and high levels of student debt has been that graduates, for the most part, land well-paid and high-skilled jobs.

A combination of the uncertainties created by advances in artificial intelligence, a glut of graduates, and depressed graduate salaries risks tearing up that contract.

For Harrington, there is a very clear first step to be taken. “The government must raise the repayment thresholds. They have made an error, and they need to fix that to calm things down.” But how realistic is another fiscal U-turn in a road littered with the wreckage from several recent policy reverses in other areas?

A proactive government would reform the system now – which means doing more than just the welcome reintroduction of maintenance grants for the least well-off. Change is needed for the masses, too – for the politically volatile squeezed middle.

Across 27 annual university guides, I have always held the view that, on balance, having a degree is better than not having one. However, without some imminent radical changes in how we as a country pay for having a better-educated workforce, I will struggle to maintain that view.

Professor Alastair McCall is deputy director of the Centre for Education and Employment Research at the University of Buckingham and editor of the ‘Daily Mail University Guide’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks