Sunao Tsuboi: Hiroshima survivor who called for peace

As co-chair of Nihon Hidankyo, a nationwide group of bomb survivors, he pushed for global condemnation of nuclear weapons

Sunao Tsuboi was on his way to university when he found himself under the mushroom cloud. While walking a little over a mile from where Enola Gay dropped the first atom bomb, the 20-year-old student saw a blinding light before being knocked unconscious. When Tsuboi came round, his body was covered in burns, and the city he inhabited just moments ago was reduced to a fiery wreck.

Like many survivors of the atomic bombs, Tsuboi, who has died aged 96, dedicated his life to campaigning for a world free from weapons of mass destruction. As co-chair of Nihon Hidankyo, a nationwide group of bomb survivors, he pushed for global condemnation of nuclear weapons and ensured that survivors’ voices were heard all over the world.

Teaching was at the very heart of the peace activist’s work, whether it was the many people who heard his testimony or the copious students he inspired while working as a maths tutor. To his students, to whom he would often recount his past in the lead-up to the bomb’s anniversary each year, Tsuboi was known as “Mr Pikadon”, or “Mr Flash Boom”.

As one of the most prolific hibakusha (“bomb-affected-people”), Tsuboi did not shy away from describing the horrific things he saw in graphic detail. “My ears were hanging off,” he recounted. “I saw tens of thousands of bodies everywhere, all burned and dead. I saw such terrible things.” When talking of survivors, he talked of people looking “like ghosts, bleeding and trying to walk before collapsing”.

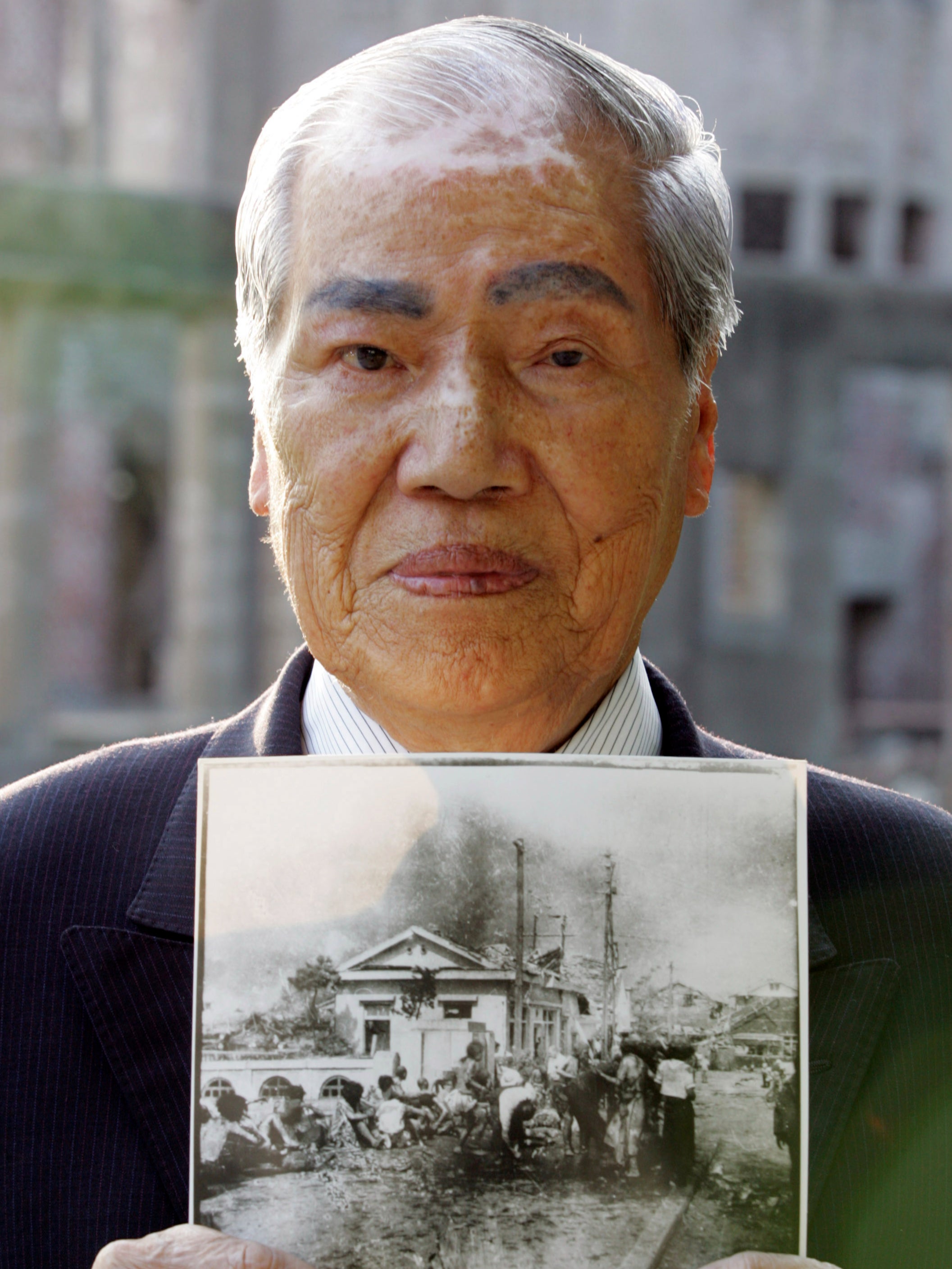

In one of the few images taken of Hiroshima on the morning of the bomb, Tsuboi, alongside other survivors, can be seen struggling for aid at Miyuki Bridge. In the photo, police are rubbing olive oil on children, the only form of relief available for many individuals in the immediate aftermath. Badly burned and believing he could not saved, the activist wrote on a pebble “Tsuboi died here”.

He was so badly injured by the bomb he had to start his recovery by practising crawling on the floor. It was months before he could even turn over in bed. Speaking about his slow recovery, he said: “My life had been spared, but I felt that just living was not good enough.”

Sunao Tsuboi was born 5 May 1925 in Ondo, on Kurahashi Island, and was the fourth of five children. His father, who died of acute pneumonia when he was in high school, was an executive at a fishing net company. As a child, he had an interest in maths and had ambitions to be an inventor.

In 1943, he enrolled in a mechanics course at the Hiroshima Technical Institute and, encouraged by a propaganda regime that emphasised war productivity, wanted to learn all he could to help serve Japan. “I wanted to make good planes and get the enemy,” he recalled in an interview. “While I was a student, all I thought about was winning the war.”

His injuries meant that a physically demanding job would likely kill him and so he gave up his dream of being an inventor. Sick and struggling to heal, Tsuboi turned to books to educate his mind. From 1946 he worked at schools around Japan before eventually retiring in 1986. Each August, when the anniversary of the bombings came round, Tsuboi would recount his story to students, wanting them to understand what it was like to survive.

Tsuboi became more involved with disarmament advocacy after his retirement. In 1993, he took on the role of deputy director of Nihon Hidankyo and in 2000 became chair. Feeling it was his responsibility to not only remind the world of the horrors of nuclear warfare but to demand states abandon any form of nuclear power, he attended events around the world. Giving as many as 70 talks a year, the activist travelled to 12 countries.

Among his many advocacy acts was his protest against the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s controversial decision to put Enola Gay on display. The plane that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima is a horrifying symbol for many survivors. Tsuboi presented a petition with 25,000 signatures pleading with the museum to acknowledge the thousands killed by the bomb and the many thousands more who were injured in its description, something the exhibition made no reference to. The Smithsonian turned down the request.

He was also a fierce advocate for the rights of the hibakusha, and pushed to have the government recognise their status as A-bomb victims and provide state support.

Tsuboi himself suffered from many health problems throughout his life, many of them linked to the lingering effects of the bomb. As well as developing aplastic anaemia, a condition that required him to have intravenous transfusions every two weeks, he was also diagnosed with cancer twice. After 1945, he was hospitalised 11 times and was told on three occasions he was going to die.

In 2016, Tsuboi was one of the many survivors to meet Barack Obama during the president’s historic visit to Hiroshima. After shaking hands with Obama, Tsuboi recalled, the president told him, “Let’s do our best to work together”. In 2011, he was awarded the Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize for efforts against nuclear warfare.

He was married to his wife Suzuko from 1957 until her death in 1992. He is survived by three children and seven grandchildren.

Every year, Tsuboi would make an annual pilgrimage to the Hiroshima Peace Park on 6 August. Wanting to honour the thousands of victims who died that day, he, along with many others, would release a lantern over the Motoyasu River to “guide” the spirits of the dead. The activist was aware that the hibakusha’s numbers were dwindling – it was his mission to do all that he could to leave a warning behind for future generations.

“My parents named me ‘Sunao’ because they wanted me to live my life on the straight and narrow,” Tsuboi said in 2013. “War, nuclear weapons, terrorism, murder – all of them are wrong. Human life is what’s most important. I will continue to proceed in a straight line toward peace.”

Sunao Tsuboi, anti-nuclear activist and teacher, born 5 May 1925, died 24 October 2021

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks