General Election 2015: 'We want to say to our children - our generation did the right thing,' says David Cameron

In his final election essay, Donald Macintyre sees the Prime Minister get passionate with the people of Carlisle

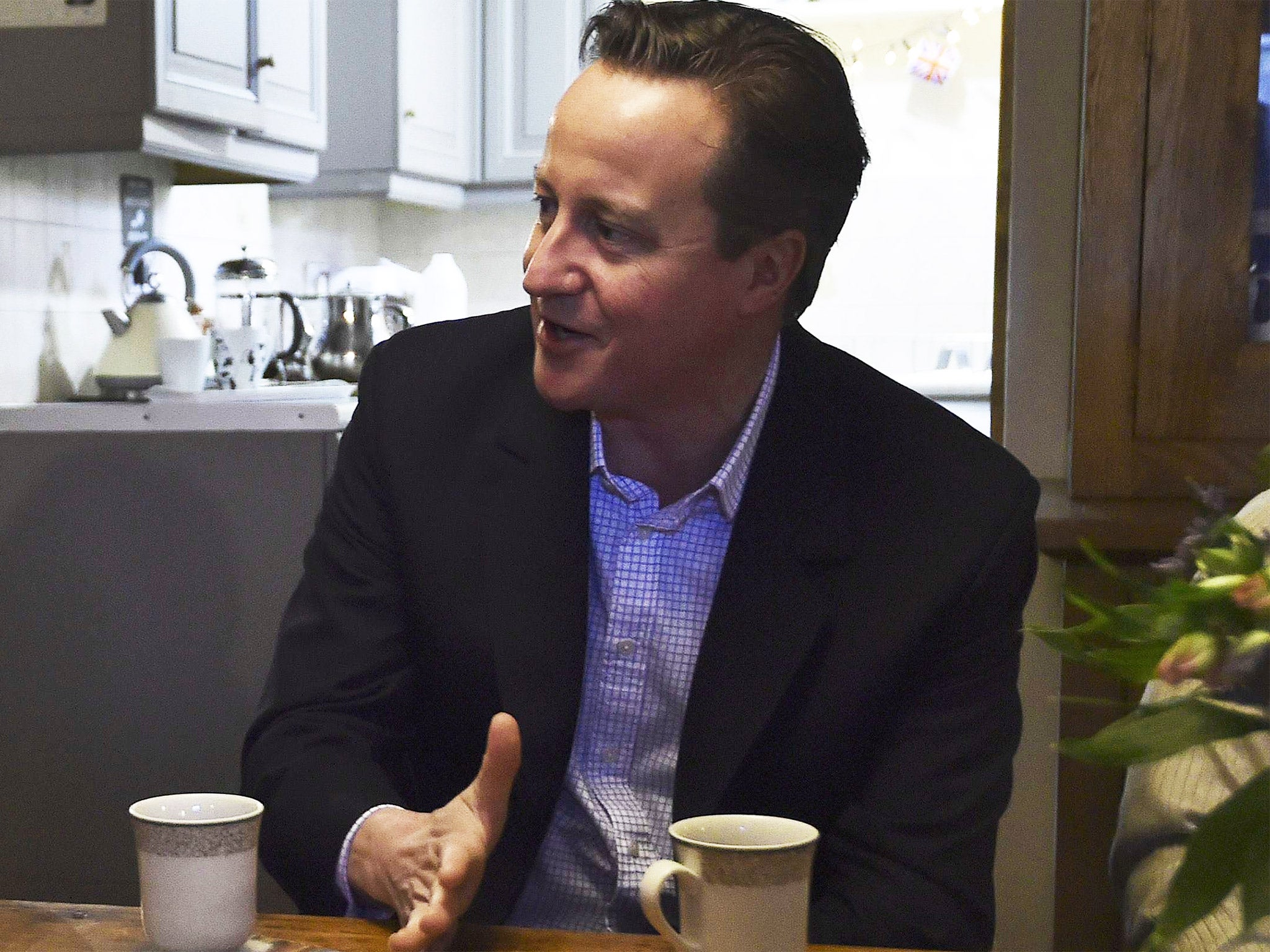

He must be exhausted. But no one could say that David Cameron wasn’t fired up at his final rally in Carlisle. In less than 20 minutes, and to euphoric applause from his Tory audience, he pulled out almost every item in his playbook including the crumpled note – it was a joke but Cameron will never let him forget it – that Labour’s Liam Byrne left at the Treasury saying there was no money.

“Do we build on the work that has been done in the last five years,” he demanded, “or do we go back to square one and waste all the sacrifice, all the work that has been done?”

Raising the rhetorical stakes still higher, he even judged it was not too late to inject a “moral” note into the last night of the campaign. “We are not trying to cut the deficit because we are demented accountants obsessed with numbers. We are doing it because we want to go home at night, look our children in the eye and say, ‘This generation did the right thing’.”

It was an odd mixture of rally and carnival, well timed for the 6pm bulletins. The huge blue banner proclaimed: “Keep Your Economy Strong”; with a strapline: “Keep a stable government” (i.e don’t let the SNP anywhere near it).

But since the venue was Carlisle’s biggest cattle market, there was a cheeky hint of animal odour in the building. And Rory Stewart, Tory MP for neighbouring Penrith, was sporting a rosette in blue and yellow, a nod to the 18th-century local landowner Lord Lonsdale’s insistence that candidates sported his colours.

But what you did realise is that this is a man who badly wants to win and can still turn it up after one of the most protracted election campaigns in British history (if not necessarily as Cameron put it, “the one that will define a generation”).

Of course there have been gaffes. The confusion of West Ham with his supposedly favoured Aston Villa may have reached parts of the electorate that other political news doesn’t. And it was all the odder because when asked who his favourite Villa player was in a Buzzfeed interview early in the campaign he speedily replied “Benteke”. Maybe he had briefed himself for it. But the one that will be remembered much longer was his gaffe – a classic one since it told the truth – of describing the election as “career defining”.

And career defining or not, there is no doubting how pumped he was as he left, pausing only for a couple of inevitable selfies, with Samantha Cameron, the Clinton-adopted Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop (Thinking about tomorrow)” blaring as usual from the speakers. He was also leading with his chin: the Tory MP John Stevenson’s majority is only 853. He declared: “It’s great to be in Carlisle after 36 hours’ campaigning”. It may not seem too great if Labour wins it.

It has been, as Cameron told his fans in Carlisle, a long campaign. It was just a fortnight ago – but seems like an age – that Cameron went to Horsforth in the marginal Pudsey constituency held by the Tory MP Stuart Andrew. (Cameron may not know this, but by a quirky coincidence this is the very village outside Leeds where the infant Ed Miliband was brought up when his father was a professor at the city’s university.)

That day, however, the shirt-sleeved Cameron was at the expanding hi-tech firm TPP, whose chief executive Frank Hester, tactfully ignoring the fact that there’s an election on, said how “delighted” he was at the opportunity to ask him some of “our straight talking Yorkshire questions”.

Cameron was just as “excited” to be making the visit. He produced the standard “statistic” that both he and the Chancellor cite on their visits to Yorkshire, namely that the county has produced “more jobs in the last five years than the whole of France”. And have continued to do even after a BBC North reporter pointed out to Osborne, also in Pudsey, that since France had seen a fall of jobs in the same period, this didn’t seem that spectacular. In Horsforth, Cameron was also sure that the “Yorkshire folk will be living up to their reputation for “plain speaking” and “tough questions”. Well hardly. As often at these workplace sessions the employees could not have been better behaved.

Victoria, a commercial manager at the company, has moved to Leeds for her job and as a first-time home buyer is pretty pleased with the Government’s Help to Buy scheme. What she wanted was an assurance that the scheme is not going to be dropped. Which, surprise, surprise, Cameron was only too pleased to give her.

Probably the “toughest” question Cameron got was from a man called Lance Christie, who said: “Now that we’re a bit more prosperous in Yorkshire and we’re fairly prosperous in Leeds would you consider giving us a motorway right the way round it because the airport and some of our businesses are fairly cut off in the present system.” Cameron banged on for a bit about transpennine rail improvements and upgrading of the M62 before suggesting that Lance has a word with Andrew, the candidate, after the session. So maybe it was a bit tough after all.

To be fair neither Cameron nor Miliband have experienced really dangerous questions from voters in this most controlled of elections – beyond the notably uninhibited audience’s starring role in last week’s BBC Question Time of course; the one exception was Cameron’s fairly raucous run-in with pensioners at an Age Concern event early in the campaign, one that has certainly not been repeated. Indeed never mind avoiding “the Gillian Duffy moment” which dogged the middle of Gordon Brown’s 2010 campaign after he unguardedly described a voter as “that bigoted woman”, and which all the party leaders have naturally been concerned not to repeat.

In pictures: Experts' predictions for the General Election - 03/05/15

Show all 10So sterile have elections become there hasn’t even been the opportunity for a Diana Gould moment. (She was the housewife who nailed Margaret Thatcher over the sinking of the Belgrano in the Falklands War on an election television programme of the sort that the BBC sadly no longer gives us.)

Which doesn’t mean that the Horsforth event wasn’t without interest. The first question was asked by Daniel, a TPP analyst, who said that he’s a diabetic and while courteously acknowledging the “large amount of the NHS budget that is spent on diabetes” suggested that there are devices that he can only buy privately which improve care and asked what can be done to “ensure that the NHS has access to cutting-edge technology”.

Cameron is at his most genuinely impressive in reply, thoughtfully saying that the “consequences” of diabetes already cost the NHS around £20m, that the NHS hasn’t always been “a great adopter of technology”, and that greater use of it would in the long run actually save money. He sounds especially well briefed on the subject but in fairness that may be because, as he points out, his father was a diabetic.

But then the event turns seriously party political. Almost certainly by accident. Like Miliband at his “People’s Question Times” the Prime Minister quite often invites “the media” to pose a few questions at the end of his “Cameron Directs”, though this, as it happens, wasn’t one of those occasions. Instead he called on “that lady over there”. But “that lady” turns out to Beth Rigby of the Financial Times who raises the Scottish Tory Lord (Michael) Forsyth’s ominous warning the previous day that his party is taking a view which is “short term and dangerous” for the Union by talking up the Scottish nationalists for the sole reason that “they see the fact that the nationalists are going to take seats in Scotland will be helpful”. In purely electoral terms.

Rigby also asks him – the still pertinent – question of whether he wants to remain as Tory leader if he fails to achieve the 23 seats that he needs to secure a majority. Everything in his body language since then screams “yes” to Rigby’s second question. But today he dispatches it with a fairly banal answer that he would indeed be “deeply disappointed” to fall short but “I’m not going to fall short” (an argument that would prove less easy to sustain a fortnight later) and the majority was needed for “strong, decisive government”.

But it’s the first question that really got him going, of course. It’s not he says – a theme which will become so much more familiar as the campaign grinds on – his fault that Labour has failed “to get its message across in Scotland”. Repeating that Labour can only “get into Downing Street on the back of SNP support”, he added that “the nationalists are not any old political party – they don’t come to Westminster with a list of interesting demands to make our country stronger and better. They come with one intention – to break up the country and create an independent Scotland. At the end of five years of Ed Miliband in Downing Street and Alex Salmond propping him up, he isn’t going to be thinking ‘isn’t the UK Parliament a great thing? No, what we want people to feel is that the government doesn’t work, the country should break up’.

“That is their intention. I’m not just saying that money will be sucked out of regions like this but if we care about our UK, I care passionately about it, don’t let the SNP into government because they will break it up.”

This went down well of course. There are however several problems with it – what Cameron (or Lynton Crosby) would make the big theme of the campaign’s closing stages. The first and most obvious is that while Cameron may be correctly defining Alex Salmond’s approach, there is no obvious reason why it should be any less so if the Tories are in power than Labour. Quite possibly rather more so, in fact since the Nationalists will be able to point to another five years of a government that Scots didn’t vote for. It’s hard to think of anything that would make it more tempting for Nicola Sturgeon to put a second independence referendum into her 2016 Scottish election manifesto.

Secondly of course he did not directly answer Forsyth’s point – or arguably the rather overlooked and even more devastating one (because he is an old Thatcher war horse without Scottish connections) made by Lord Tebbit who suggested that it might be reasonable for Tories who cared about the Union to consider voting Labour where it was the main challenger to the SNP in order to save the Union. And while it’s true that Cameron can’t be blamed for the hollowing-out of Labour in Scotland he certainly has to take some responsibility for flagging up the issue of English votes for English laws the day after the – dare one say “career defining” – victory for the No camp in September – leaving Scots who voted No wondering whether the influence they thought they would retain over the UK government might soon be evaporating. Not to mention the risk he is taking with the Union – which Labour isn’t – by promising an EU referendum which if England voted No and Scotland Yes would irresistibly turbo-charge the SNP’s demand for independence.

So while this may have worked well – and it has certainly played on the doorsteps these last three weeks as Cameron proclaimed in Carlisle, not adding that this is partly because he never stops talking about it – it is a much more flawed argument than Cameron made out in Horsforth or in Carlisle or in all the places in between.

But of course this is all about Cameron’s attempt to question the “legitimacy” of a Labour government whose Queen’s Speech may be supported – probably without any Labour-SNP negotiation – by the nationalists, and will become part of his second campaign to remain in Downing Street if he ends up at the head of the largest party, but without an overall majority. As the former Cabinet Secretary Lord O’Donnell has pointed out, the real key to “legitimacy” is the simple one of who can get a Queen’s Speech through. That is actually the only real constitutional principle that matters.

Of course Cameron’s intention to stay in office follows the precedent of Stanley Baldwin after the November 1923 election; Baldwin stayed in office as the leader of the largest single party even though the Liberals and Labour together formed a majority, presented a Queen’s Speech which was subsequently voted down; and the King sent for Ramsay MacDonald who then formed a government.

What is making Labour restive, though, is the prospect that if the Tories become the biggest single party in the present fairly hysterical media climate the taunts about “legitimacy”, however flimsily based, will make its job much harder than it was – at least, at first – for MacDonald in 1923-24.

Not only will Cameron’s cheerleaders in the press scream “highway robbery” and “coalition of losers” at Labour’s aspiration to govern, but it may influence the possibly wavering Liberal Democrats to stay away from Labour.

Worse still there could even be a repeat of the “friendly fire” from Blairite figures like David Blunkett and John Reid which helped to sabotage Gordon Brown’s efforts to form a (rather less solidly based) minority government in 2010. It could need iron discipline to prevent some Labour MPs giving up and signing up for another five years in opposition.

Miliband is said to believe that one key reason for the Cameron approach is that he needs to prevent a potentially lethal revolt by his own backbenchers deeply disgruntled at a second failure to win an overall majority, a failure possibly involving the loss of 30 or more seats to Labour. There may be an element of this.

And of course if Labour were to be the largest party, Cameron would have to go. And even if he does “win”, not every Tory MP relishes dependence on Northern Ireland’s DUP. “They’re politically conservative but economically socialist,” said one last week. “They’ll just want more and more and more money. But the conventional wisdom that prevailed for a time after 2010 that Cameron could only survive a second election as leader if he won an overall majority, is now obsolete.

Watching Cameron among the party’s excited supporters in Carlisle, it was impossible to deny that he has plenty of fight left in him. The idea that he was deep down resigned to leaving office, seemed something of a fantasy. He is still despite the stumbles a formidable campaigner, and surely one still addicted to power. But important as the arithmetic is to what happens next, his campaign may well not be over. The second, and even more bitterly contested, phase could begin on Friday.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies