‘All we want is to learn’: Gaza’s children growing up without schools

As children worldwide go back to school, their Palestinian counterparts are still waiting for their education and classrooms to be rebuilt and restored. Esraa Abo Qamar reports from Gaza on how they’re coping

When Hassan Alsarafndi was six years old, he had a happy life with a loving family. He lived in a beautiful house in Rafah, at the southern end of the Gaza Strip, along with his parents, two sisters, and brother. He was full of life, always cheerful and playful, excited to start first grade in elementary school so he could learn the alphabet. He couldn’t wait to read and write.

But 7 October 2023 changed everything. Israeli airstrikes and ground operations destroyed entire neighbourhoods, forcing hundreds of thousands of families to flee their homes and leaving schools, hospitals, and basic services in ruins. Hassan’s world quickly turned into a life of displacement and fear.

More than two years later, Hassan is now in the third grade, and he still can’t read or write properly.

His mother, Heba, 34 years old, explains: “We are already under huge pressure; we can’t find time to teach him. Even if I give one hour, it is never enough. Normally, students at his age take a week or two to absorb a lesson, but I can’t provide him with that on my own.”

Since October 2023, Gaza’s education system has collapsed. More than 650,000 students have been left without schools, with nearly 95 per cent of facilities destroyed or severely damaged. This January marks the third consecutive year that children and students have been deprived of their education and right to attend school.

According to Unicef, at least 87 per cent of schools will require significant reconstruction before they can function again. The United Nations has warned that rebuilding Gaza’s infrastructure could take “anywhere from 16 years to more than 80 years, depending on the pace of reconstruction”. In its humanitarian situation update, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) stated that the ongoing crisis in Gaza will set children’s education “back by up to five years and risks creating a lost generation of permanently disadvantaged youth”.

“It breaks my heart,” Heba said. “Hassan has already lost two years of schooling, years he can never get back. I can see the difference so clearly. Missing these two years didn’t only take away his education; it took away the environment that shapes children, the place where they make friends and learn confidence and good manners. School builds them in ways we sometimes forget, and he’s been denied all of that. His older siblings were reading, writing, and building dreams at his age, but he spends his days carrying big responsibilities and concerns.”

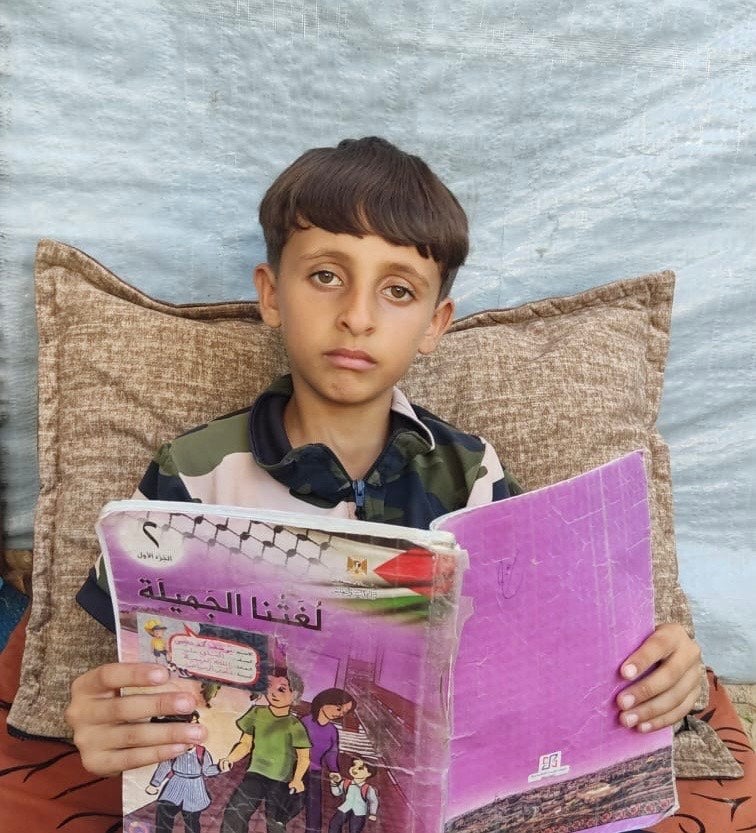

Hassan’s story reflects the experience of a whole generation growing up without classrooms, books, or teachers. He once dreamed of writing his name on a school desk, surrounded by his friends and laughter. Now, he struggles to hold a pencil inside a crowded tent, where he and all his family live, eat, and sleep.

Young children typically learn through listening and repetition, but this takes time and concentration. Hassan is always distracted by the noise inside the tents and the new responsibilities he now has, from filling the water buckets to waiting in queues to bring lunch from the takiyya (a meal distribution centre often organised by local charities). He can’t find a good time or place to practise and study.

Constant hunger has further undermined children’s abilities to learn in Gaza, compounding the effect of displacement and stress. According to Unicef, when children lack adequate nutrition in early childhood, their brain development and cognitive capacity are significantly impaired, which directly affects their ability to concentrate, retain information, and succeed in school. Children like Hassan, who are deprived of essential nutrients, are more likely to fall behind academically, and compromised learning and development will have a lifetime of consequences.

Having no resources to study from creates another obstacle. Schoolbooks are unavailable, and notebooks and pens are so expensive that average families cannot provide them. “I wish I had my own desk,” says Hassan. “I want to organise my notebooks and colours like I used to see my older siblings do.”

While children worldwide are preparing to go back to school after the holidays, Gaza’s children are still searching through the rubble of their classrooms, waiting for the day their right to education is restored. If a ceasefire has come, it must mean more than the silence that follows the bombs. It needs to be the beginning of rebuilding, not only the schools, but the hope and future of children like Hassan, who deserve to grow up without the scars of their stolen childhood and disrupted education.

Students need face-to-face education with their teachers. Ohood Nassar is a 23-year-old student from northern Gaza. She started an educational tent in the western area of Gaza City in November 2024. Her first attempt included around 30 students from grades 1-3; many of them had very low educational levels due to having been cut off from formal schooling since 7 October. She noticed that while the children’s psychological state was generally normal, as the situation in their area at that time had not yet escalated, their academic skills were severely affected.

After the ceasefire, Ohood transformed a shelter tent near her home in Tal al-Zaatar into a learning space, eventually hosting around 100 students from grades 1-7. “At the beginning, I expected teaching to be similar to my experience in west Gaza, but I quickly realised it was very different. Most students had witnessed severe trauma, and many were orphans, having lost one or both parents,” she explained.

To help the children cope, Ohood did more than just teach – she incorporated games and activities that improved their mental wellbeing. “The educational tent became like their second home,” she said. She also received support from the Gaza Great Minds (GGM) organisation, which provided supplies like tables, chairs, and learning materials – resources she could not have afforded on her own.

Her initiative, called al-Ohood School, was officially recognised by the Ministry of Education, marking it as the first accredited educational tent in northern Gaza. Despite ongoing shelling and displacement, she continued teaching as much as possible, helping children practise reading, writing, and storytelling. “Even under these conditions, ensuring the children receive some form of education is crucial,” said Ohood. The educational tent is now considered a red area (danger zone) because Israeli troops and soldiers are still there. Ohood – who is now displaced in central Gaza – believes it has been burned.

It isn’t just younger children who are suffering – it’s university students too. Mariam Mushtaha, a student at the Islamic University of Gaza majoring in English language translation, is struggling to continue her education. Currently in her third year, Mariam describes her journey as filled with endless obstacles, similar to many other students in Gaza.

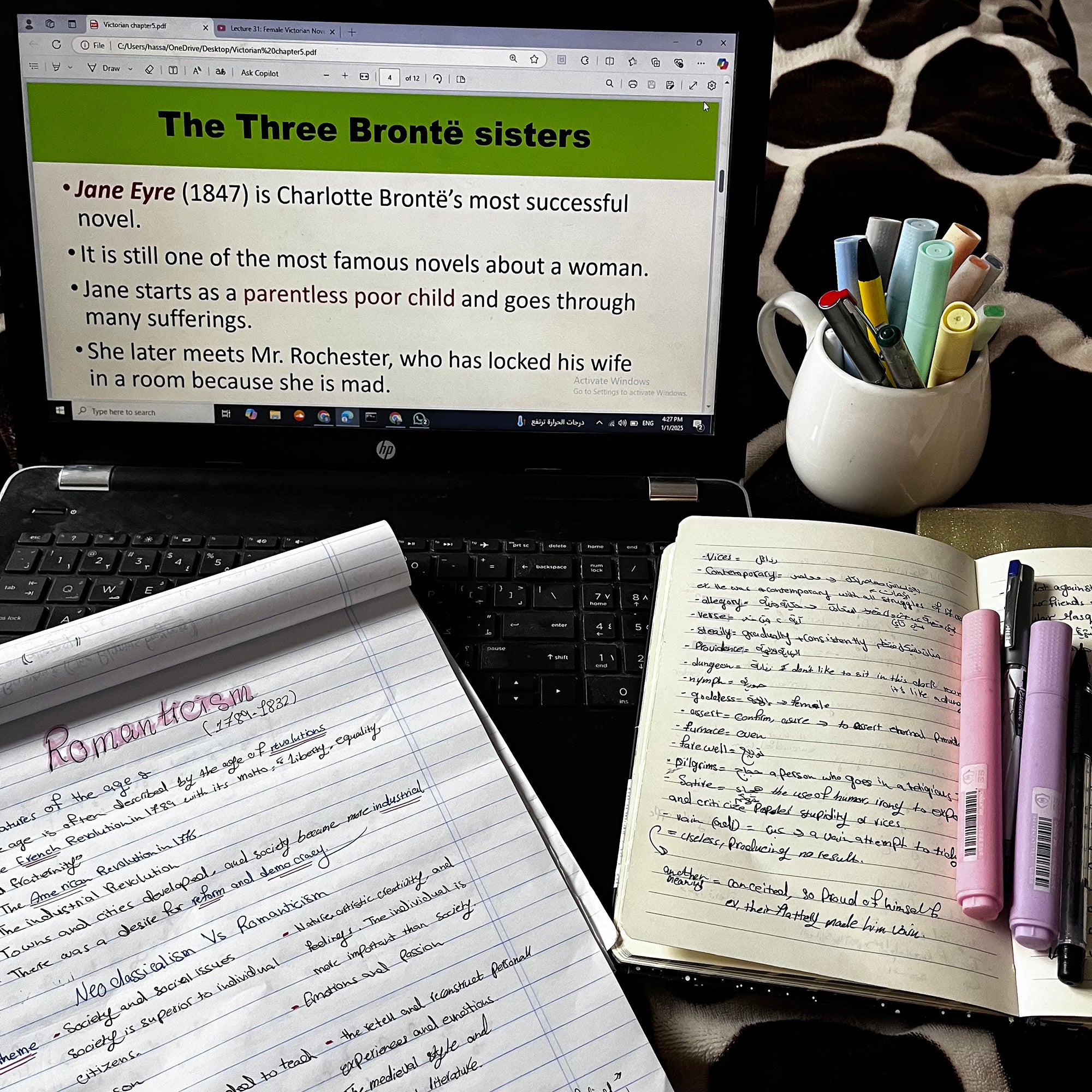

In July 2024, when the university announced the resumption of classes online, Mariam and her family were displaced into a small, overcrowded house with her aunts. “The house was very small, and there were many people, including children. It was not easy at all for me to study,” she recalls. Despite her reluctance to study behind screens, her parents encouraged her: “We are not sure when the war will end; it’s better not to waste more time in your life.” Motivated by their support, Mariam managed to continue her studies.

She had to study at night after the children had gone to bed, sleeping during the daytime. Sometimes she used the balcony because the internet connection was stronger, but studying there was unsafe, especially when she needed to turn on a light. “I had no other choice; I could not find a proper space to study,” she explains.

By January 2025, Mariam had completed her first year with a high GPA. However, her family had to leave the house they were staying in and search for a new home in Tel al-Hawa, where there was almost no internet. The displacement meant all the workspaces with electricity and internet were far away. “I had to walk long distances under the harsh sun just to download lectures or complete exams,” she says.

Transportation was another major issue. Fees had increased fivefold, and cash shortages made it difficult to pay taxi drivers, especially with old or torn bills. “Sometimes I thought of withdrawing from the semester, but I kept telling myself that I had come so far, I had to continue,” she adds.

Even in her second year, Mariam continued to face unstable internet, electricity outages, and the constant stress caused by Israeli threats. “All these challenges could have weakened me, but instead they have strengthened me. Knowledge deserves fighting, and we deserve to be educated,” she says, looking forward to graduating and achieving her dreams of becoming a translator and English teacher.

Education in Gaza has received less than 15 per cent of the required humanitarian funding. Unicef also warned that this remains one of the most underfunded sectors in Gaza’s humanitarian response, leaving teachers unpaid and learning programmes unsustained. As a result, even temporary learning spaces such as Ohood Nassar’s initiative rely entirely on volunteer work and small donations rather than a stable educational system.

The damage is not merely educational; it’s deeply psychological. A report by the World Health Organisation (WHO) found that children in Gaza are experiencing severe trauma symptoms, including anxiety, sleep disturbances, and withdrawal, all of which hinder their ability to learn. Missing consecutive academic years destroys foundational literacy and numeracy skills, making recovery almost impossible without intensive long-term support.

The attacks on Gaza have left more than ruins behind – they have carved deep scars in the minds and futures of thousands of innocent children. An entire generation is growing up without the chance to learn, to read, or to dream freely about a secure future. These are not just numbers; they are the faces of children like Hassan, still struggling to hold a pencil, and young women like Mariam, fighting to study despite all her suffering.

“I hope the world finally sees education here as a priority, not an afterthought,” says Mariam. “We need real support, rebuilding schools, restoring universities, giving us books, teachers, and a safe place to learn. We want the chance to build our future. If the world helps us do that, then maybe this January can be the beginning of something better.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks