My friend Zohran Mamdani is the new mayor of New York City. This is what he’s really like

It was at a small family dinner that the then 28-year-old Zohran Mamdani told Ruchira Gupta that he wanted to go into electoral politics. Six years on, he has been elected mayor of New York City. His was an old-fashioned victory, she writes, rooted in honesty and principle – just like the man she knows him to be

I remember the first time Zohran Kwame Mamdani spoke seriously about entering electoral politics. It was 2019, and four of us were at dinner in Manhattan – his father, the scholar Mahmood Mamdani, along with a mutual friend, Zohran, and me.

The restaurant was quiet enough to allow for a conversation without performance. He didn’t ask what it would take to run for the position of mayor in New York; he already knew the mechanics. What he wanted was ideas – what kind of politics New York needed, what principles should guide someone young and unconnected to big donors or political families – and to understand whether it was still possible for electoral politics to be rooted in ordinary people.

When I asked him the most obvious question – “Do you want help raising money?” – he thought for a moment before answering. “Not from one big donor,” he said. “From many people.”

If he entered politics, he intended to build a base broad enough that no single donor could buy influence. It recalled Mahatma Gandhi’s belief that the means are the ends in motion: you cannot build a democratic politics through plutocratic shortcuts and expect it to serve democracy on the other side.

He worried that the Democratic Party had drifted away from ordinary people, that it had stopped standing alongside unions and started to court hedge-fund money. If he ran, he wanted to do it the other way round – door by door, block by block.

Throughout our dinner, his father listened without lecturing. Mahmood – a Gujarati Muslim from Uganda and one of the most respected writers on colonialism – seemed proud of the clarity his son had reached. He has spent his life studying how power draws boundaries, deciding who belongs and who is excluded. His son was now asking how to redraw those lines.

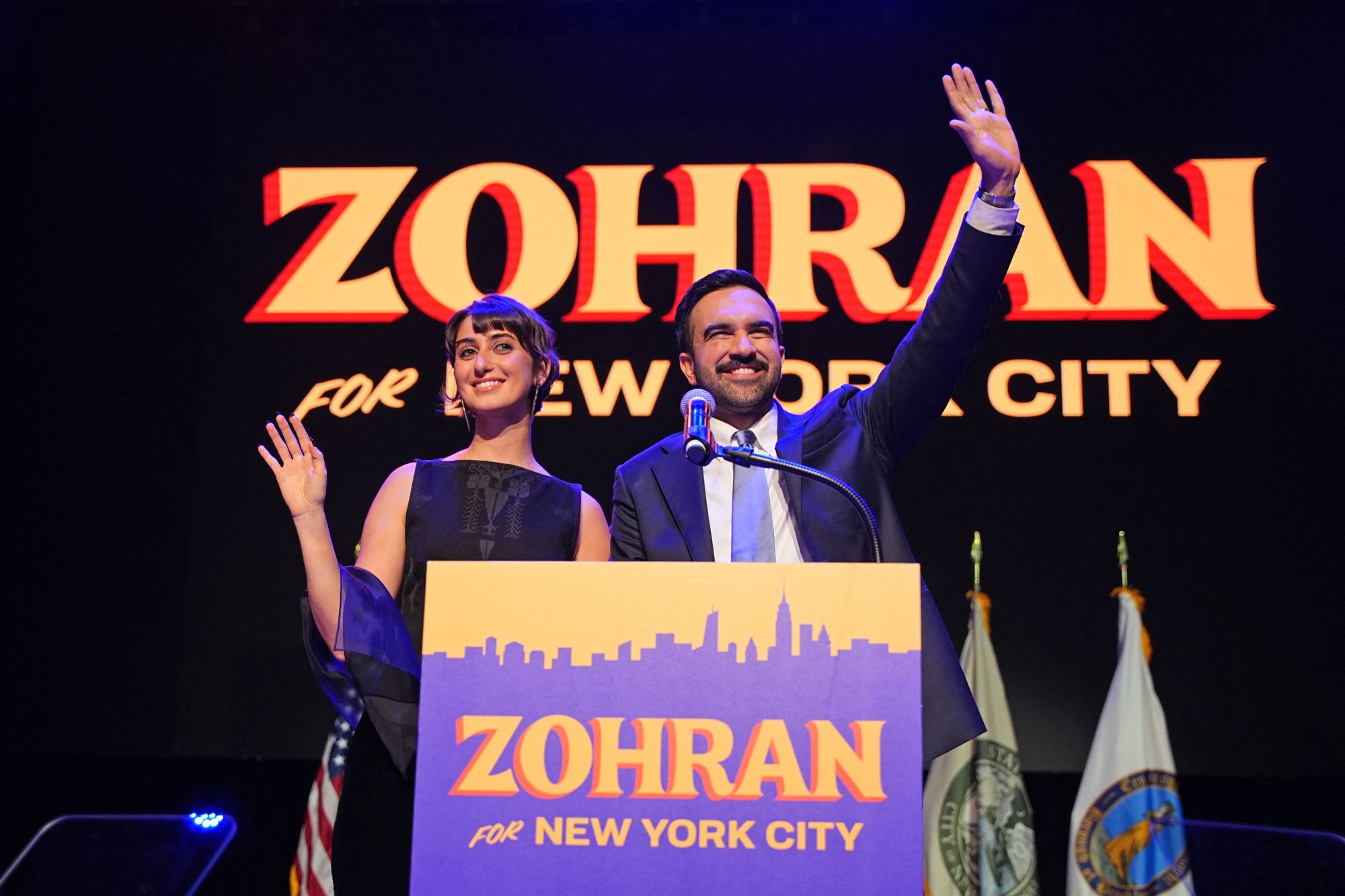

Six years later, New Yorkers elected Zohran mayor.

Commentators have been quick to credit sharp messaging, social-media fluency, smart alliances, a touch of charisma. All were factors, but not on their own sufficient.

His victory was predicated on more old-fashioned elements: honesty, principle, and grassroots organising. From the primary to election day, more than 100,000 volunteers – taxi drivers, students, tenants, aunties, vendors – knocked on over 3 million doors. They persuaded neighbours who had never met a candidate before. There was no algorithmic magic. It was manual.

This was politics the way it used to be: unglamorous, relational, and unavoidably slow.

His campaign didn’t dance around issues; it faced them. Housing was central. In America’s richest city, 150,000 children are homeless, and countless young people postpone having a family because they can’t afford rent. He talked about school segregation – an obscenity in a city that prides itself on diversity. He talked about public transit – because a family’s life can hinge on a bus timetable. He talked about small businesses – cafes, halal carts, bodegas – where the economy is a human encounter, not a statistic.

It spoke to his family values – and I had known the family for years. All of them – his Indian filmmaker mother Mira Nair, his father Mahmood, and Zohran himself, moved fluently between cultures. His parents met while Mira was making Mississippi Masala, her film about Ugandan Indians; their son grew up between Kampala, Delhi and New York. Pluralism wasn’t just an idea to him: he lived it.

He spent part of his childhood in Uganda while Mahmood was writing there, and learnt the beat of African music; he attended the progressive Bank Street School, where his first political act was helping to organise an anti-war event. His father had given him the middle name Kwame, after Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, a former president and revolutionary. It wasn’t a blueprint; it was a compass.

Later, at Bronx Science, he learnt what he calls the democracy of the subway – how a long bus ride cuts into the working day of people who need it most; who gets a school near home; where wealth sits; who gets stopped and frisked, and who gets waved through.

In Delhi, he experienced the easy traffic between faiths and cuisines in a household shaped by Nehruvian socialism. Slogans like “unity in diversity” and “simple living, high thinking” were part of everyday life. That was the material of his politics long before he found a label for it.

By 2019, he had already campaigned for Bernie Sanders, and democratic socialism made sense to him – not as fashion, but as a way to deliver the basics: rent security, good schools, buses that work.

I remember an email he sent me during those early campaign days. He could have written a simple thank-you; instead, he spoke candidly. Having looked up my work, he discovered that I oppose the decriminalisation of pimping and brothel-keeping.

“I know that this issue is very important to you,” he said, “and I want to be transparent about where I stand ... While we do have differing views on this issue, I would still like to work with you on this campaign, on building a New York that works for the many, and on fighting fascism wherever we may find it – in India, America, or anywhere in between.”

In today’s political culture, where disagreement is treated as disqualification, this stood out. He was not triangulating or soothing; he was stating his position and keeping the door open. The message was simple: principled disagreement is not rupture. We can argue, and still work together. This is rare.

His political lineage isn’t a religious inheritance but a movement one – from labour organisers, tenant activists and democratic socialists. That background is reflected in how he moves through the city. The son of a Hindu Punjabi mother and a Muslim Gujarati father, married to a Syrian-American wife, he is as comfortable in a Jackson Heights kebab house as in a Manhattan cafe. When Donald Trump once mocked him for eating biryani with his fingers, Queens saw only familiarity.

And that ease matters. In a moment when majoritarian politics hardens across continents – India included – he embodies the alternative: an everyday, habitual inclusiveness that requires no announcement.

The question now is whether he can govern according to the same commitments on which he campaigned. The work ahead is material and measurable: stabilising rents; keeping schools diverse; protecting small businesses; improving buses; ensuring workers are paid enough to live in the city they serve; subsidising grocery stores for the poor; expanding childcare. It is not glamorous. It is democracy.

That is the point. Authoritarianism thrives when public life breaks down – when housing collapses, when transit fails, when neighbours retreat from one another. Democracy survives when people can live decent lives: housed, mobile, safe, and heard.

This is the mundane truth that strongmen never acknowledge: order is not achieved by fear, but by fairness.

Mamdani’s politics is not radical in its promises; it is radical in its method. It insists on accountability to the many rather than the few. It treats disagreement not as betrayal, but as ordinary. It takes positions rather than dodges them. It makes the case, knocks the door, and stays.

My thoughts return often to that Manhattan dinner: a young man, thinking carefully, refusing shortcuts. A father listening. A conversation about fascism, and about whether electoral politics could still be used as a tool against it.

He answered not with a theory, but with a method: not one big donor – many people.

He chose his side before he ever entered the ballot. The people have now chosen him.

If he governs as he campaigned – patiently, visibly, and in daylight – he may yet remind us of something we are in danger of forgetting: that democracy is protected by citizens being unwilling to give up on each other.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks