‘This is the future of our game’: How AI is transforming tennis, according to the coaches using it at Wimbledon

Tennis has undergone a data revolution over the past decade, writes Lawrence Ostlere. But now artificial intelligence is delivering new levels of instant game-changing insight – which may soon be accessed on the court

Andre Agassi lost his first three matches against Boris Becker in 1988 and 1989, but then won 10 of the last 11 they played. “I didn’t understand how he could read me like that,” Becker later said, perplexed by the grip Agassi held over his serve, somehow able to anticipate the direction of every ball. It was only after their careers had ended that Agassi revealed his secret: he had spotted a tell in Becker’s tongue, which would unconsciously point to where he was aiming as he tossed the ball.

It is the most famous example of tennis espionage, one perhaps never to be repeated. But there is a modern equivalent in the priceless insight tucked by the knees of every coach at Wimbledon this week: an iPad brimming with ATP Tour data about the opponent. Data on serve direction, data on landing spots, data on exactly which type of shot they most frequently miss, with AI deployed to make sense of it all. The platform is called Tennis IQ.

Since rules were relaxed in 2023, coaches have been able to communicate with players during matches, which has coincided with a major step forward in technology. Generative AI is able to answer niche questions about forehand returns in an instant, to the point where the technology is now making live recommendations for how to change the momentum of a match.

“There’s been a huge shift over the last 24 months on what you’re getting during the match,” says Andy Murray’s former coach Dani Vallverdu, speaking to The Independent on a terrace overlooking the All England Club. “Service patterns, shot selection patterns, spin of serves… You can give a lot of information that can really help turn a match around.”

Vallverdu is currently at Wimbledon coaching the Bulgarian Grigor Dimitrov, the world No 19, who is on a deep run into the second week.

“Yesterday he was struggling for a part in the match with the second-serve return. So I’m seeing that as I’m coaching, but it’s difficult to keep track in your mind of serve, serve pattern, speed. So then I go on [Tennis IQ ] and I’m like, OK, second-serve returns, he’s won fewer points in the second set. Then I go on the opponent’s second serve – where has he been serving? Has he been mixing the serve a lot more? I have a feeling that he’s been mixing the speed but now I have proof. So then I can say, look, second serve, be ready, he’s mixing the speed a little faster or slower.”

Coaching, particularly during matches, is all about trust. Players can be a tetchy breed in the heat of battle, about as receptive to instruction as a toddler getting dressed in the morning. But coaches are harder to ignore when they have the landing spot of every serve at the tap of a screen.

“It’s a lot easier for the player to believe the information the coach is giving, because it’s not just me saying, ‘Oh, I think he’s mixing more.’ I’m telling him that because I’m actually seeing it on the tablet, which is 100 per cent accurate.”

Data is hardly new in tennis. The sport has experienced a data revolution over the past decade, with tech companies battling to fill the space. In 2017, Novak Djokovic was the first superstar of his era to employ a data analyst, eager to learn more about every point he lost, obsessed with fixing the flaws in his near-perfect game.

“Novak was always so receptive to finding out new things about himself,” says Craig O’Shannessy, Djokovic’s strategy coach from 2017 to 2019, who has been working with several players at Wimbledon this week. “That was something that’s always separated him from the pack – his thirst to get better and understanding that he’s not played the perfect match, he’s still losing a bunch of points, so how can he improve that? How can he get 1 per cent better?”

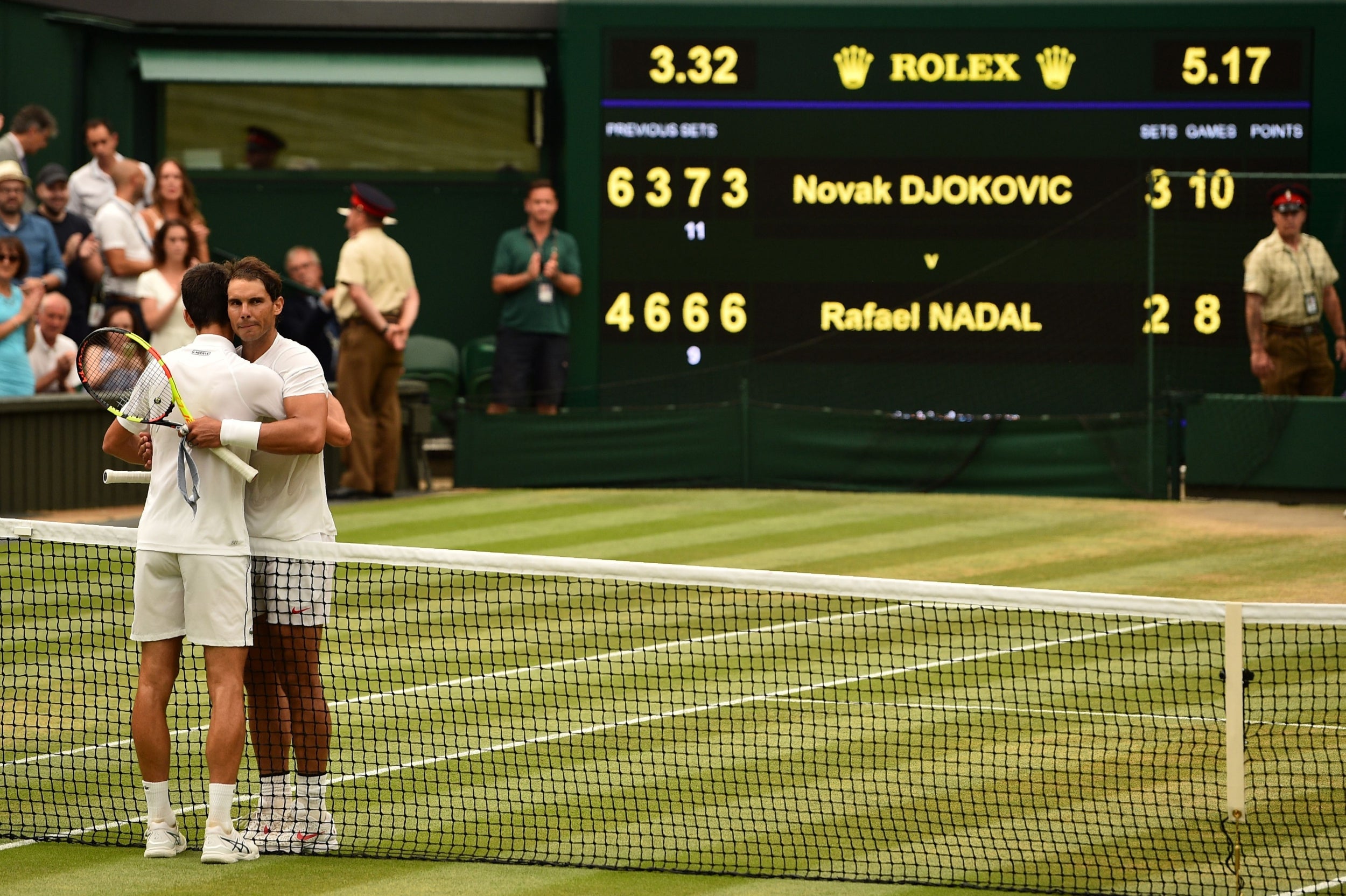

O’Shannessy cites Djokovic’s epic 2018 Wimbledon semi-final with Rafael Nadal, when play stopped overnight. Despite Djokovic’s 2-1 lead, he was struggling to get to grips with Nadal’s serve, breaking it only once in the first three sets, so O’Shannessy woke early the next day to pore over the numbers and footage.

“What I noticed was that in the first three sets, Rafa had not missed a single backhand return in the ad court. He put every single backhand return in play. So I went and watched those points, and he was sitting on it – he knew Novak was going there because in the ad court you’re fearful of going wide to Rafa’s forehand. Those serves down the T were being punished.”

O’Shannessy met Djokovic and his coach Marian Vajda that morning before the semi-final resumed.

“I said, you have to serve out wide because Rafa is jumping to the middle. By the time Novak is hitting the serve, Rafa has moved a great distance and he’s now covering the backhand. In that fifth set especially, Novak was down 15-40 a couple of times and he escaped, and a big part of that was serving to the forehand of Rafa on those big points. Without finding that, I don’t think Novak wins that match.”

O’Shannessy’s nugget of gold required hours sifting through data to identify a pattern – time afforded only because the match was suspended overnight. That is why, until now, data has been used in tennis mainly for pre-match scouting and post-match analysis, when there is time to disseminate the vast forest of information.

Now AI generates pre- and post-match reports within minutes, and what it also makes possible is for a problem to be solved during a match, courtside, with either a simple prompt or, increasingly, suggestions of its own accord. A player might be told they win 74 per cent of points which are less than four shots, but only 35 per cent when rallies go past seven shots.

For a coach, it is like having a genius assistant beside them with world-beating knowledge of both the tennis court and Excel spreadsheets.

“You’re already getting that where, as the match is going on, the AI system is identifying certain patterns of play that are giving you more success than others, without you even asking,” says Vallverdu. “So you’re getting told the top three, let’s say, patterns of play during a match that are giving you a higher chance to succeed in the point.”

It requires some practice using the tools and some coaches are more up to speed than others. Not everyone is convinced by it, and some of the old-school breed still prefer the eye test and a notepad on the knee. But the programme is available to every coach, making it fair across the board.

“That is a big difference from just three years back,” says Oivind Sorvald, technical coach to the Norwegian Casper Ruud. “Everyone had to try to find footage and look up information, and then someone bought a little bit from the big analytic companies, and not everyone had the same. Now, I think it’s a little bit more fair when all players have the information through ATP.

“The future, for the next three to five years, I think it’s going to look a lot different. I think it will be more and more common to utilise this information live. I think that coaching teams will definitely, in the future, look at what happened in the first set, they will start to train their player on the court to see what we can give you for information to change your strategy for the next sets and so on. I think that will be the future of our sport.”

Vallverdu is keen to stress that data is only one part of a tennis player’s armoury. It is a game of technique, physique and mental fortitude, and there is no replacement for a player’s intuition on the court, for gut instinct. But knowledge is power, and knowing that your opponent is serving down the T on every break point is invaluable.

“AI has been a game-changer,” he says. “Right now it is not yet defining the outcome of matches, but it is supporting in a big way.”

Vallverdu’s worry is that the next step might be to sidestep coaches completely, and that players could one day soon be seen sitting on Centre Court with an iPad in front of them at the change of ends.

“The way it’s trending, whether the players can look at it or not themselves, whether they can have a tablet themselves as they’re playing – we could end up there. Do I believe it is the right thing to do? I don’t think so. I think it should be left to the coaching team to digest the information and to know what to share.

“You might get to a point in a few years’ time where the player is sitting down and clicking a button or putting in some headphones, and he’s getting the AI to tell him, ‘Look, when you’re standing six inches to the left, actually you’re returning the wide serve better, you're getting cleaner contact, you’re getting better depth on the return’. But hopefully they’ll keep that with the coaching team and not the player.”

What is certainly coming is more sophisticated video technology which will whip through match footage to produce choice clips from an opening set. And there will be a switch from a decade’s focus on ball data – speed, spin, trajectory – towards body mechanics, such as insight on the optimum wrist angle when serving.

“You will now be able to track every [body] movement in a way that has never been possible,” says Lauren Pedersen, the CEO of SportAI, a Norwegian company which counts chess grandmaster Magnus Carlsen among its investors. Coaches might not have that kind of power at the fingertips this week, but they could do very soon – “by next year if they really lean into it,” says Pedersen.

So it is not hard to imagine that AI will soon be able to read the body of an opponent, to search for physical traits in their game. Thirty years after Agassi read Becker’s tongue, the idea of a machine spotting the same thing is not so far-fetched.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks