The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Harar: exploring Ethiopia's holy Islamic walled citadel

The medieval Unesco World Heritage Site, where khat and coffee are king, contrasts sharply with this largely Orthodox Christian nation

“Faranjo! faranjo!” is the repeated shout in the backstreets of Harar, in the nearby hill villages and from the depths of the camel market. The word means quite simply “foreigner” – essentially, you’ve been spotted, usually by excited children. Otherwise Harar Jugol, a Unesco World Heritage city – said to be Islam’s fourth holiest city on account of 82 mosques – that was once a prosperous, independent kingdom, lives a strangely insular existence. This fortified desert city was built between 13th and 16th centuries and is also home to 102 shrines and townhouses that reveal exceptional interior design. During the sizzling afternoon heat, its male inhabitants seemingly disappear; I soon gather it is the khat habit that keeps them indoors in a beatific daze.

This staunchly Muslim enclave in the far east of Ethiopia, a country renowned for its Orthodox Christian beliefs, was founded in the 10th century and is one of the oldest Islamic cities in East Africa. In spite of the proliferation of mosques, the muezzin are discreet, and only the occasional dome and the main Jami mosque serve to remind of its cultural stature.

Meanwhile, the spaghetti-like maze of lanes and alleyways of the walled medieval town teem with industrious women, gossiping, bartering at the sprawling street market, buying grain at the teff mill to make spongey injera flatbread, choosing colourful fabrics or stocking up on aromatic spices. All are dressed in extravagant hues, although the flowing styles differ wildly according to each ethnic group: Oromo, Argobba, Somali or Adares. A few rare men are bent over treadle sewing machines on Makina Girgir street – makina being inherited from the short-lived Italian colonisation of the 1930s, and girgir from the whirring of the tailors’ antiquated Singers.

With its colourful façades (turquoise, fuchsia, mauve), the magical old town, Harar Jugol, cannot fail to seduce, even if one of the first foreigners to set foot here, in 1855, the British explorer Sir Richard Burton, fled after 10 days, unimpressed by the poverty, mangy dogs, “loud and rude” voices and “laxity of morals” (“intoxicating drinks, beer and mead”).

In contrast, 30 years later, the French poet, coffee-trader and ultimately gun-runner, Arthur Rimbaud, settled in Harar for 10 years. Although his various abodes have long since disappeared, a grand, old, Indian merchant’s mansion now houses a museum full of his grainy photos and other century-old images. The poet is also honoured in the new town by Charleville Street, named after his hometown in the Ardennes. Now this central avenue swarms with turquoise Peugeot 404s from the 1960s, recently rivaled by imported Indian bajaji (auto rickshaws).

A couple of streets from Rimbaud’s museum, in an equally ornate Indian mansion, is the private museum of cultural specialist Abdela Sherif. Packed with Quranic manuscripts, coins, jewellery and costumes, it is proof of Harar’s once thriving status as a trading crossroads that lured Armenians, Portuguese, Arabs and Indians to deal in ivory, coffee, cotton, tobacco and slaves (the latter only ended in the 1930s).

Today such exports have been largely replaced by the stimulant khat, a lucrative crop that has its production and frenetic all-night market just north of Harar, at Awaday. From here it is trucked at alarming speed to Somaliland’s eager consumers, about four hours to the east. When we set off to Babile to see the camel market, Isuzu trucks roar past us, interspersed by the odd herd of ambling camels led by semi-nomadic Hawiya. Life seems to operate at two speeds.

We find the livestock market in full swing in the arid hills of the Eastern Rift Valley where, beyond, unfolds the Valley of Marvels, an enchanting landscape of surreal rock formations where dromedaries occupy one section and goats and sheep the other. Abdul, our guide, explains that camel bidding is by silent finger pressure, so no one else knows the price offered.

It is all orderly and strangely quiet, though the pace shifts up a notch in the bleating goat and sheep section where women traders energetically count fat wads of birr. Old men with henna-bright beards, sunglasses and necklaces watch us curiously, while a shouted “faranjo!” occasionally penetrates the murmurs. And of course there are women selling bunches of fresh khat and lethargic male camel-owners flat out in the shade of a tea-stand.

Afterwards we bounce up dirt roads into the hills around Koromi to visit eastern Ethiopia’s coffee-farmers, the Argobba. Greeting us outside their simple, stone houses are women dressed in decorative, vibrant colours, scarves, earrings and necklaces. It may be dry in the valley below, but here mountain streams flow freely. However one woman shares her concern about the drought in north-eastern Ethiopia, adding that “the spring rains haven’t come here either”. The Longberry arabica coffee that they grow using centuries-old techniques – cultivating and drying by hand on small, family-owned plantations – is considered one of the world’s top beans so, back in Harar, I dive into the coffee mill to buy a one-kilo packet (£5) to take home.

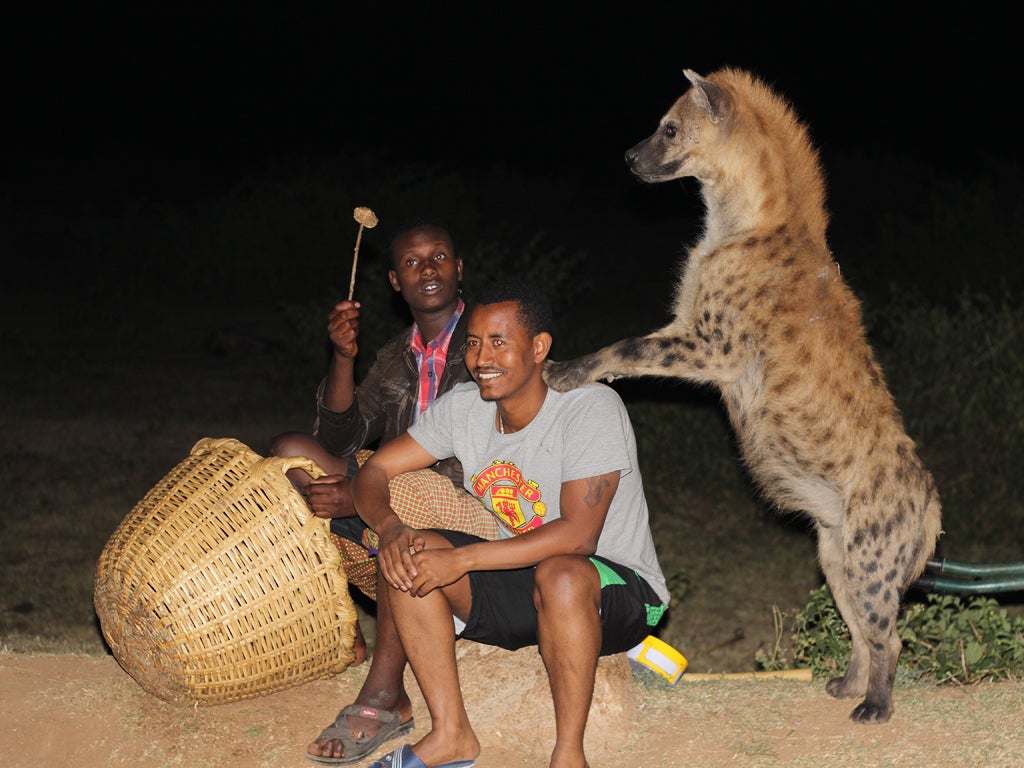

Just before nightfall we head outside the walls to see perhaps the city’s most curious custom: hyena feeding. One lone man, the sixth generation of a Harari family to do this, sits beside two large baskets of meat scraps and bones as some 20 hyenas materialise from the inky night. The huge, spotted mammals circle, then, as he calls them individually, home in to be fed chunks from a stick, illuminated by car headlights for the enthralled faranjo. Developed as a ploy to preempt attacks in town, the sunset feed has also become a minor tourist industry.

On my return home, cup after cup of rich Harar coffee propels me back to that bewitching place, its cloistered people, colours, camels, khat and prowling hyenas.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Ethiopian Airlines (ethiopianairlines.com) flies daily from Heathrow to Addis Ababa, with connections for Dire Dawa (for Harar). The onward journey takes around one hour by bus. The alternative is a nine-hour bus-ride from Addis Ababa.

Local tour operators such as Awaze Tours (00 251 11 663 4439; awazetours.com) can arrange a three-night Harar package including flights, driver, guide, Ras Hotel, meals and excursions from US$800 per person.

Staying there

Ras Hotel, Charleville Street, Harar (00 251 25 666027): in the new town on a noisy avenue but acceptable comfort for Harar, with Italian Art Deco touches, hot showers, bar and restaurant. Doubles from US$40 including breakfast.

Rowda Waber Guesthouse (00 251 666 2211; 00 251 92 187 2867). A popular, seven-room traditional guesthouse in Harar Jugol with shared facilities. Rates from US$25 per person including breakfast.

More information

Bradt’s Ethiopia by Philip Briggs, 7th edition £17.99 (bradtguides.com).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks