Wales has mastered the art of beautiful gloom

I love it that the Welsh have a positive - indeed, greedy - genius for melancholy

I am, if anything, Welsh, so I know what it is to be despised and rejected. And so, when Howard Jacobson won the Man Booker Prize with The Finkler Question, his flamboyantly Jewish novel, I wrote to him saying: "Congratulations from one persecuted minority to another. You are brilliant at literature, but we are very good at rugby." Jacobson immediately shot a reply to me saying: "We could have been good at rugby too, but wanted to leave you something."

Even the Welsh dislike the Welsh. Dylan Thomas said: "Land of my fathers, and my fathers can keep it!" Funny, but unfair of the Rimbaud of Cwmdonkin Drive to say so. My wife and I have reason to go to Wales, and Wales always demands we return. With neither borders nor security, our regular journey from south London to north Wales is one of my favourites, because it's a 200-mile graphic of the universal pains and pleasures of travel.

Leaving London is the familiar grinding misery that gets more profound as you approach Birmingham. Only after about 150 miles of motorway anxiety, just after Shrewsbury, do you begin to feel the gravitational force of London draining away. Just a few more miles on the A5, then turn off at Knockin, feeling thrillingly free.

Into the beautiful Tanat Valley now, and after half an hour on a road gently winding through intense greenery, we are in Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant. We are far away, but, in a sense, I have come home and that is what we seek in travel.

I love it that the Welsh have a positive – indeed, greedy – genius for melancholy. The poet Gwyn Thomas said: "There are still parts of Wales where the only concession to gaiety is a striped shroud." Indeed, the Welsh contribution to man-made beauty is not first-rate. How strange it is that grandiose nature seems often to stimulate architectural mediocrity. Outside Llanrhaeadr is a small cluster of houses that would bring the gulags into disrepute.

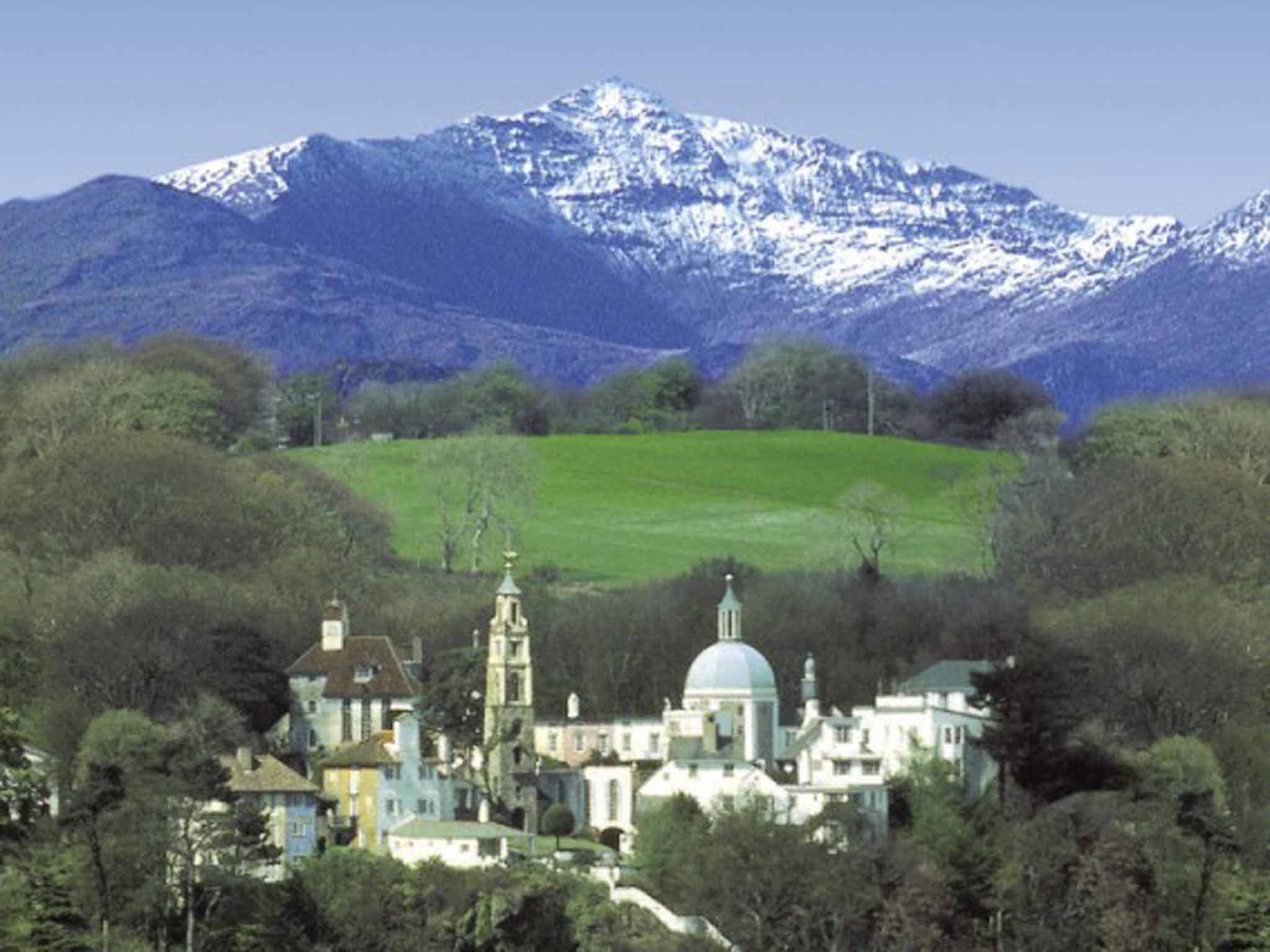

Nearby is Clough Williams-Ellis's paranoiacally surreal Portmeirion where we were once detained by a harrowingly violent thunderstorm. You can see why The Prisoner felt trapped here. Also down the road is Lake Vyrnwy, where villages were drowned to irrigate an ungrateful Liverpool. Even in sunlight, Vyrnwy looks grim. At mysterious Pennant-Melangell you'll find one of the oldest Romanesque shrines in the country, and the haunting legend of an Irish virgin saint and her adventures with a hare and a prince.

In 1893, W B Yeats published Celtic Twilight, inspired by the folklore of Sligo and Galway. There's only a quantum of semantic difference between the noble "twilight" and more essentially Welsh "gloom". Great pleasure can be had from connoisseurship, and in Wales you can be a connoisseur of beautiful gloom. Or so I think as, after three nights, I load-up the car for the return journey. I dislike leaving Wales, but want to get back to London and another version of home. That's why a journey is such a perfect miniature of the traveller's eternal perplexity.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies