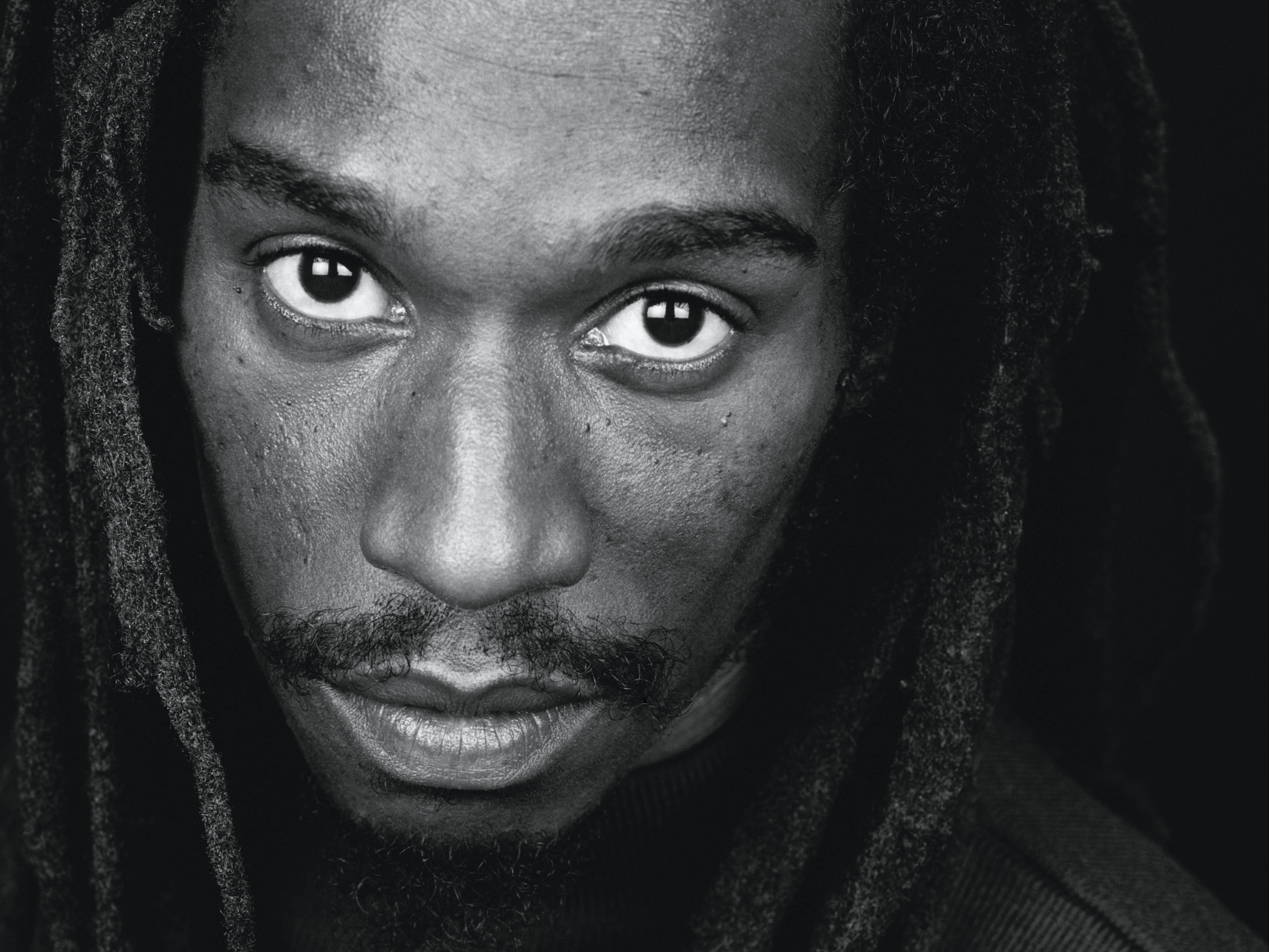

Benjamin Zephaniah was the heart and consciousness of Black Britain

The dub poet and national treasure did not try to fit in. Instead, he embraced the language and rhythm of his upbringing – and in doing so, he changed the establishment, writes academic and activist Kehinde Andrews

I’ve never been one to mourn celebrities. I have never really understood the logic of being sad that someone I don’t personally know has passed away. Until now, that is.

Even though I never met Benjamin Zephaniah, it feels like I knew him. His words and presence have always been there. No doubt, this is in no small part because he was a Birmingham icon, who grew up just down the road from me in Handsworth. He physically left the city as a young man, but Birmingham never left him. It was ever present in his accent and his commitment to his hometown.

His role in Peaky Blinders as Jimmy Jesus, a real-life Jamaican soldier from the 1920s, was the perfect role for him; an icon of the city, set in its iconic show. Zephaniah was a voice for the Black community in the UK in general, but Birmingham in particular. It is impossible to overestimate how much an inspiration it was to see a Black writer from the neighbourhood rise to prominence in the Eighties.

What made Zephaniah so special was that he didn’t change himself to be popular. He stayed true to his roots, his politics and himself. His dub poetry rose out of resistance to racism, hallmarked by his Rastafarian faith.

When Caribbean children first came to Britain in large numbers in the Sixties, they were deemed “education subnormal”, because of their “patois” – which was seen as “broken English”. Rastafarians were demonised as unruly ghetto youth, to be feared and policed. When the urban rebellions rocked the nation in the Eighties, in places like Brixton and Handsworth, the soundtrack was reggae – and the lyrics captured the resistance at the heart of Rastafari. These revolts further criminalised the image of Rastafarians and their trademark dreadlocks are still seen by some as a sign of dysfunction that can get a child banned from attending school.

But Zephaniah did not try to fit in to English poetry society or British society overall. Instead, he embraced the language and rhythm of his upbringing – and in doing so, he changed the establishment. He was dyslexic, left school at 13 and went on to become one of Britain most revered modern poets and a professor at Brunel – all while keeping his dreadlocks. Representation can often be a diversion from real change, but with his integrity and authenticity Zephaniah truly made a difference.

Yet he never let his fame or ambition get in the way of his politics. He remained on the front line of protest, marching against the Iraq invasion and for his cousin Mikey Powell, who died in Birmingham in police custody.

His poetry called out racism and he had harsh words for Black people who climbed the ladder and pulled it up behind them.

His principles were immortalised when he publicly rejected the Order of the British Empire (OBE) offered by Tony Blair’s government in 2003. His rejection was classic Zephaniah, when he wrote that his first thoughts were “up yours” to the invitation. Writing directly to those in power, he said: “No way Mr Blair; no way, Mrs Queen. I am profoundly anti-empire.”

At the time, this was a stunning breath of fresh air from someone not only refusing to play the game, but publicly rebuking those in power. We didn’t have social media back then. His notoriety was forged within the community; conversations about him were blasted straight into the mainstream. His poem, “Bought and Sold”, to me perfectly captures the feelings of what trying so hard to fit in was doing to Black artists:

Smart big awards and prize money

Is killing off black poetry

It’s not censors or dictators that are cutting up our art.

The lure of meeting royalty

And touching high society

Is damping creativity and eating at our heart.

This is one of my favourite Zephaniah poems – the description embodies everything he was not.

He will be sorely missed. He represented the heart and consciousness of Black Britain in a way that few ever have. He was the “people’s laureate”; a voice for the community that was so clear and unapologetic that it always cut through.

In honouring his memory, we should always remember to speak the truth loudly – and most of all, never change ourselves to seek “success”.

Kehinde Nkosi Andrews is a professor of Black Studies in the School of Social Sciences at Birmingham City University. He is the author of Back to Black: Retelling Black Radicalism for the 21st Century (2018) and Resisting Racism: Race, Inequality and the Black Supplementary School Movement (2013)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks