The findings that the UK intelligence agencies knew of torture during the Iraq War reveals the dark side of the special relationship

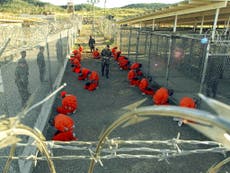

The only thing the British seem not to have done (probably) is actually waterboard the prisoners concerned or bundle them onto the planes to Guantanamo Bay

The report of the Commons Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC), for all its lawyerly hedging and cautious caveats, could really not be clearer. The British government, through its security agencies, acquiesced in the use of torture during the war on terror after 9/11. It was “inexcusable”. During the subsequent invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, of Iraq and a variety of other military and covert operations, MI5 and MI6 were complicit in what was euphemistically described as “extraordinary rendition” – official extrajudicial kidnappings and illegal detention. The British helped to fund such operations, supplied intelligence to facilitate them, knew more widely about cases of maltreatment, directly witnessed some 13 identifiable examples, and usually did nothing about it, and went along with the American way of war for many years.

There is precision in numbers as well as wording in the report. There were 25 incidents where British personnel were told by detainees that they had been abused and 128 where UK intelligence and security officers were told by foreign counterparts about mistreatment. In some cases they were “properly” investigated, but not consistently. In 28 cases, UK agencies agreed to rendition operations proposed by others.

The only thing the British seem not to have done (probably) is actually waterboard the prisoners concerned or bundle them onto the planes to Guantanamo Bay. Apart from that, pretty much anything went, it would seem.

So it is a damning report. The select committee is chaired by Dominic Grieve, better known now as a crusader for parliamentary rights over Brexit. He is a former attorney general, and his carefully chosen phrases in the report beg some further questions. When, for example, the ISC says that there is “no smoking gun” to suggest there was a deliberate policy to overlook prisoner abuses, that does not mean there was no tacit policy to do so – merely that they can’t find an email or a minute that sets it down. Culturally it was obviously tolerated. Similarly, the ISC states that there is “no evidence” that British personnel directly carried out physical mistreatment of detainees – again, this does not mean that no such thing ever took place.

It will be countered that those the American, British and other allied forces were up against in the region were no angels. The Taliban, Al-Qaeda, Isis and all the other groups were hardly enthusiasts for human rights, and their abuses put whatever allied troops or spies did into some sort of perspective. Yet no one expects western forces to operate outside the rule of law or the international conventions on warfare, “asymmetric” or not.

If Isis throw gay people off the tops of buildings, would that make it OK for the Americans or British to start doing the same? Precisely the same question applies to torture, unlawful detention, denial of a fair trial and all the other abuses we become so wearily familiar with, including the obscene mistreatment of captured Iraqi soldiers in American controlled jails, captured in photographs taken like holiday snaps by US troops.

The point about the war on terror was that it was a war for human rights, and forces fighting for human rights should not be involved in directly or indirectly violating them. Evidence gained via torture is not admissible in law and, many experienced service personally believe, is unreliable at best. There is, as the committee says, no excuse for getting involved in it, no matter how tangentially.

There should be political accountability for all of this. The then prime minister, Tony Blair, and foreign secretary, Jack Straw, plainly had cases to answer. Despite all the many inquiries into the Iraq War, some aspects remain stubbornly unclear, and for no good reason. The Labour Party, through shadow attorney general Baroness Chakrabarti, has called for a judicial inquiry. That will be necessary, because the questions must be answered properly.

It would be better all round, though, if Mr Blair and Mr Straw, and any other ministers around at the time, voluntarily made a more detailed response to the ISC report and listed their part in and knowledge (if any) of some shameful and counterproductive activities.

As matters stand today, what the Blair government said at the time undermines trust in politics and gives conspiracy theories unnecessary credence. Mr Straw, for example, told a parliamentary committee in 2005 (also taking the opportunity to speak for the then US secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice): “Unless we all start to believe in conspiracy theories and that the officials are lying, that I am lying, that behind this there is some kind of secret state which is in league with some dark forces in the United States, and also let me say, we believe that Secretary Rice is lying, there simply is no truth in the claims that the United Kingdom has been involved in rendition, full stop, because we have not been, and so what on earth a judicial inquiry would start to do I have no idea. I do not think it would be justified.”

No doubt Mr Straw would interpret his phrase “involved in rendition” differently to Mr Grieve.

In policy terms, the ISC concludes that the British could have done more to influence the Americans, but chose not to – the fear was that the UK would lose its privileged access to US intelligence. If so, then the question is at what price are we paying for this special relationship with the US?

The more that seeps out of the official machine about what the intelligence services and the politicians knew and did in the 2000s, the more we understand about what a judicial inquiry would start to do and why such an inquiry would be justified.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies