These authors’ books are some of the most challenged in the US. They’re speaking out

Maia Kobabe, Ibram X Kendi, and Susan Kuklin speak to Clémence Michallon

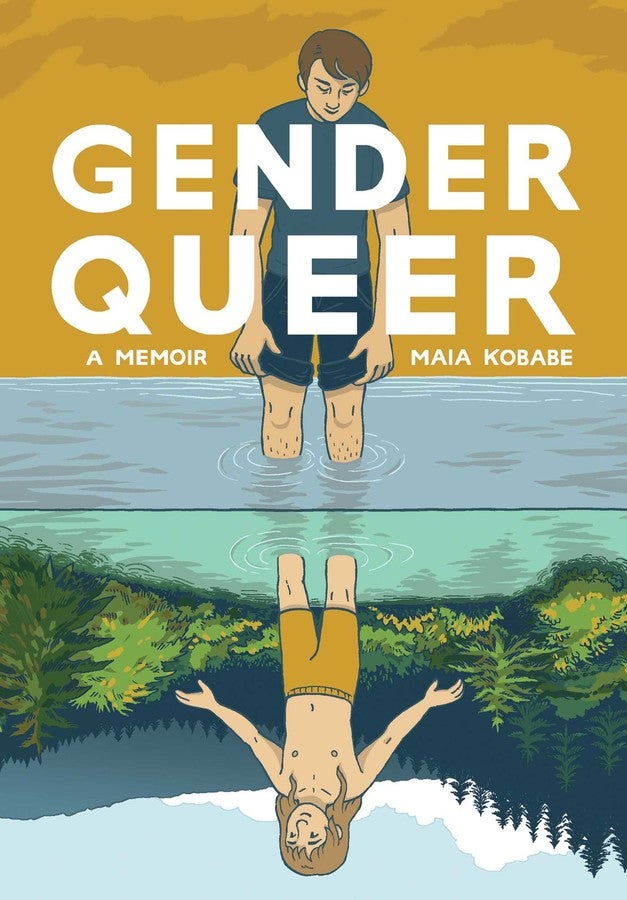

In the fall of 2021, Maia Kobabe, a cartoonist and author of the 2019 graphic memoir Gender Queer, came upon a paragraph in a report by the American Library Association (ALA) on banned books. Kobabe, who uses e/em/eir pronouns, says this was eir first inkling that the book was facing challenges. It was, in fact, the most challenged book that year by the association’s count.

“Very shortly after that issue was released, a parent in a Fairfax, Virginia, school district loudly challenged my book and shared excerpts in a school board meeting which was filmed and went viral on social media,” Kobabe tells The Independent in an email. “This challenge was the first spark of a chain reaction which hasn’t slowed down to this day.”

Kobabe is one of multiple authors The Independent spoke to, whose work has been a target in the recent influx of book challenges by conservative groups in US public schools. The ALA, which has tracked book challenges in libraries and schools, reported a record number of demands to censor library books and other materials last year. There were 1,269 such demands in 2022, according to the association – almost twice the number recorded in 2021, when there were 729.

Over the course of those demands, 2,571 unique titles were targeted. “Of those titles, the vast majority were written by or about members of the LGBTQIA+ community and people of color,” the ALA noted.

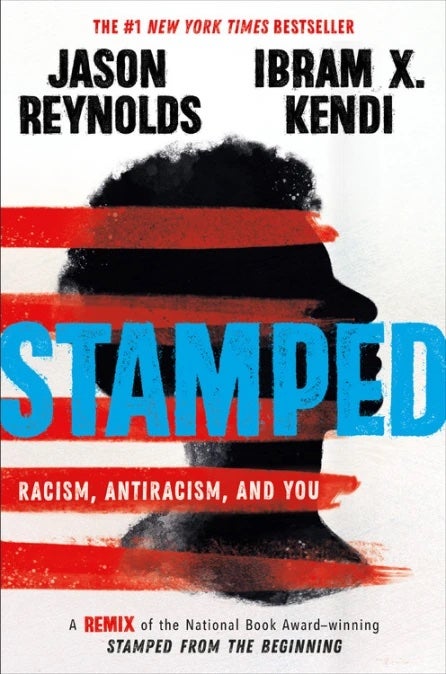

In 2020, one of the ALA’s 10 most challenged books was Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, a nonfiction book about racism and antiracism in America, co-authored by Ibram X Kendi and Jason Reynolds for young readers, and published that same year. For Kendi, like Kobabe’s experience, the book’s presence on the ALA’s shortlist (it was the second most challenged book of 2020) was the first sign the book was being targeted.

“On the one hand, it was enraging, because we’re writing these books so that children and even adults can learn about the world that they’re living in so that they can contribute to creating equality and equity and justice for all. And so, to think that there are people out there who don’t want those books is quite disturbing,” Kendi tells The Independent in a phone interview.

“On the other hand, as an historian, I know that books by abolitionists were banned. I know that books by civil rights thinkers were banned – really, any book that did not share a sort of Lost Cause history in the Jim Crow South was banned. This is just the latest iteration. Before, it was enslavers and Jim Crow segregationists, and now you have this current flock of people banning anti-racist books.”

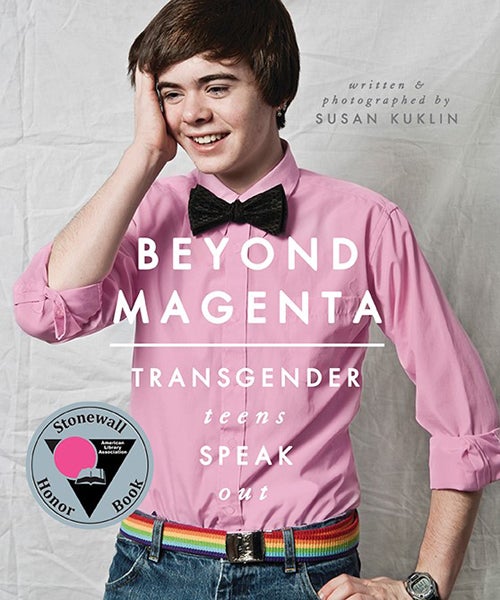

Also on the ALA’s shortlist in 2015, 2019, and 2021 was Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out, a book by photographer and writer Susan Kuklin. It tells the stories of six young people, all transgender or nonbinary. Kuklin began researching the book in 2010. She interviewed and photographed all six participants individually, working closely with each of them.

“It has been a great honor to be trusted with the participants’ stories,” she tells The Independent in an email. “A privilege. A sacred trust. As we worked together, I felt extremely close to the young adults and their families. At times, my maternal instinct would pop out and I felt the need to protect them. I rationalized, naively, that if I didn’t include some of the tough parts of their life, they would go away. (This was a fleeting feeling, to be sure.) I had to remind myself that the best support and protection I could give the contributors was to let them be their authentic selves.”

When Kuklin’s publisher informed her, the year after Beyond Magenta’s publication, that the book was on the ALA’s shortlist, she was surprised.

“At first, it felt odd,” she tells The Independent. “Why now? Why would anyone want to prohibit another person’s truth, especially when it was not designed to harm any others? Very quickly, I became angry. I’m still angry. Here were six decent, honest, brave young people speaking out to help others and to define themselves in their own terms only to be told to shut up. That sends an ugly message that they and, implicitly, many others are unacceptable, that they do not matter. Well, they do matter.”

To Kobabe, learning that Gender Queer was being challenged was “deeply frustrating, for many reasons, one of which is that many people who challenge my book proudly claim that they haven’t even read it.”

“But in a wider sense, it feels like just one piece of the current wave of conservative efforts to erase trans, queer, nonbinary, and other minority voices from the public sphere,” e adds. “Book challenges in schools have led to legislation in some states, most notably Florida, which limit the queer and Black history that teachers are allowed to share in the classroom.”

Kobabe cites Florida House Bill 1467, which increases parents’ ability to challenge books in school media centers. “All across the US, states are introducing legislation to ban drag performances, healthcare for trans minors, health insurance coverage for trans medical needs, banning trans students from participating in sports and using public restrooms,” e tells The Independent. “It’s not just about books, it’s about making life actively harder and worse for queer and trans people across the country.”

So, what of the young readers who might benefit from reading Kobabe’s, Kendi’s, and Kuklin’s words, but can no longer find their books at school?

“I would encourage those kids to figure out ways to access those books online,” Kendi says. “Or if you could organize fundraisers, you could buy the books for yourself as well as your classmates. They can’t really stop us from buying the books at our local bookstore ourselves. And I would encourage young people to get involved in the efforts to ensure that they have access to all books. Throughout this nation’s history, when adults were doing things that were restricting their education, young people typically organized together and pushed back.”

Kuklin, too, points would-be readers to the internet, where Beyond Magenta is available in digital and audio formats.

“My advice about how to get access to the book causes a bit of a conundrum because, on the one hand, I believe parents should have the right to decide what their children can or cannot read. But by the same token, other parents should not be deprived of their right to decide what is best for their children,” she writes in her email. “On the other hand, it is important that the full range of young people see themselves in literature. The fact that in some communities in the US, young adults, whether questioning or not, do not have access to my and other LGBTQAI+ books in some schools and libraries is becoming a very big problem.”

Kobabe hopes young readers remain curious and determined to read a broad range of materials: “To young people who are seeing my book and many others removed from schools and libraries, I would say: people who ban books are always on the wrong side of history.

“People who ban books are trying to limit your education, your potential, your window into the wide, beautiful, complicated, diverse world. Don’t let them make you afraid; don’t let them limit your curiosity. The books they are trying to take from you are probably the ones you’d find the most revolutionary.”

Unsurprisingly, Kobabe says these book challenges have had a negative effect on eir life.

“The book challenges have wasted a lot of my time, but they have also massively increased my book’s sales and my platform as an author,” e says. “I spent more time doing interviews and less time drawing than I did before the media attention, but it also helped me sell my second book. What I have learned is that book challenges don’t really negatively impact a book or its author; what they negatively impact is the community where the challenge takes place and the readers whose rights and access to information are removed. Across the nation, I see conservatives impoverishing and attacking their own communities, which is terrible. But it’s only made me more determined to keep writing stories centering trans, queer, and nonbinary characters.”

Kobabe doesn’t “think the people who are banning my book would listen to me,” but if they did, e would tell them: “There are many things that could be done to improve the safety and happiness of children in school, but banning books isn’t one of them.

“If you want to protect and support students, advocate for reforms in gun ownership, in free lunch programs, for teacher’s raises, for increased budgets for arts, science, music, sports, after school programs. Think of ways to provide more resources to students, not less.”

Kendi says that even outside the realm of book banning,”people have always deemed the idea of racial equality, and [the idea that] the problem is bad policies and not bad people to be controversial.”

“We’ve always had to prove that there’s nothing wrong or inferior about Black people. We’ve always had to demonstrate the importance of the American people learning about the experiences that are distinct for different groups in this country,” he says. “So I’ve always had to be quite careful with what I’m saying and what I’m writing, and as a scholar, ensuring that I’m speaking from the standpoint of evidence and research.”

What’s been most challenging for him, he says, is “witnessing people misrepresent or distort what my books are about in order to justify banning them.” “They don’t want to say, ‘This book is expressing to children that we’re all equal,’ even though that’s what’s true. Witnessing people not only ban books, but lie to people about the books that they’re banning, has been difficult.”

Kendi urges people to get involved in their local or state politics.

“That involvement could be joining a local organization that’s fighting against book banning. That can mean fundraising or funding that kind of organization, that could mean running for a position of power on the school board, that can mean talking to teachers and librarians and asking them how they can be supported,” he says. “Teachers and librarians are, in many ways, on the front lines. Their profession, their intellectual capability, and their skill sets have been completely demonized and dismissed. That’s one of the most tragic aspects of this: We’re not allowing teachers and librarians to do their jobs.”

To Kendi, there is a direct link between book banning and tyranny. “If people were to think about the most extreme, harmful, and violent tyrants in recent human history, chances are those people were banning books. Chances are they were not allowing for the truth, for evidence, for science, for multiculturalism to be put forth,” he says.

“Book banning has long been an indication of some of the most tyrannical forces in human history. If they can ban books, and those books contain experiences and cultures and beliefs and characters, then the next step is literally banning those people, their cultures, their experiences, their humanity.”

Especially striking, to him, is that “the book banners are claiming that the authors that they’re banning are trying to indoctrinate people – even though one of the most effective ways to indoctrinate people is to ban books.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks