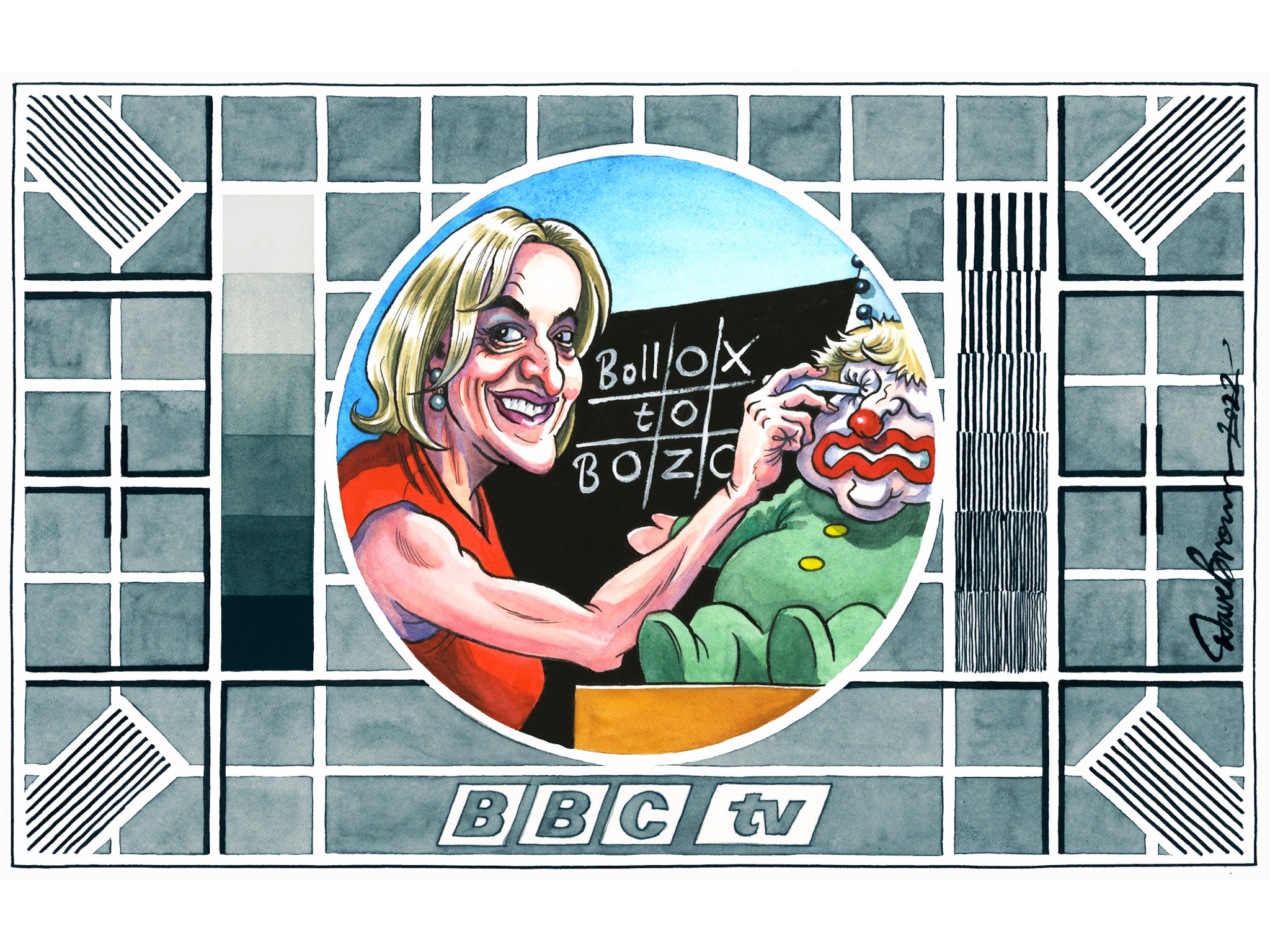

What Emily Maitlis gets wrong about BBC impartiality

Impartiality is the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow – it is enshrined in BBC producer guidelines and legislation, but its practical application moves with the times, writes Sean O’Grady

I may be one of the few people with a genuine admiration for both Emily Maitlis, an excellent journalist, and her apparent bete noir, Sir Robbie Gibb, also an excellent journalist but better known as the former head of communications to Theresa May, and therefore a Big Tory, and nowadays BBC board member.

According to Maitlis, Gibb is almost some kind of fifth columnist within the corporation, or an “active agent of the Conservative Party” as she puts it in unnecessarily conspiratorial terms, who is shaping the broadcaster’s news output by acting “as the arbiter of BBC impartiality”. The implication – no, actually, her fairly explicit claim – is that he is unsuitable for such a role.

I’m not sure about that. Certainly, anyone who had anything to do with the creation of GB News, as Gibb did, can’t be contemplated entirely with equanimity, though it’s fair to add that the foam-flecked, anti-vax, Meghan-obsessed, Reform UK propagandist, conspiracist station of today is even more unbalanced than the one that, presumably, Gibb and Andrew Neil envisaged as livening up the broadcasting ecosystem. The precedent it set, blessed by the then culture secretary Oliver Dowden, has been a disastrous experiment.

Even so, I had the pleasure of working with Gibb many years ago when he was a political journalist with the corporation and found him far from an “agent” of the political right. He was certainly someone with firm views and sometimes pungent opinions, his voting habits were no secret, and his devotion to Michael Portillo verged on the manic. But journalists usually have their passions and pet hates, even if they affect bloodless neutrality and are unwilling to admit them.

Gibb was impressive because he combined unusually strong feelings about politics with an equally pronounced taste for civilised, respectful debate and could keep his prejudices in check when the professional need arose, which was nearly all the time. Interestingly, as a libertarian sort of Conservative, and occupying crucial roles in the political output, he was also a standing indictment of the lazy claim people made that the BBC was full of communists. It never was, and there were always more Tories around than anyone outside seemed to realise. Indeed, those with Conservative sympathies, and therefore accompanying insights and contacts, were prized by the editors of political programmes seeking balance and an “in” with Tory ministers or spads.

Gibb was no slavish apologist for the Major government of the time, and he didn’t think much of the European Union, but that was nothing unusual. Indeed, looking back, it’s interesting how the two prime ministers of the 1990s, John Major and Tony Blair, came to power deriding their predecessor’s anti-Europeanism and full of optimism about Britain’s place “at the heart of Europe”, yet soon enough grew frustrated and disillusioned by Brussels and all its works.

Which brings me to Brexit. If Gibb was and is trying to ensure the BBC produces balanced, impartial output in the eyes of as wide a public as possible, then it is no surprise he’s going to come in for a kicking. Maitlis may be right in some theoretical sense that the Brexit argument isn’t balanced because the economic case is and was so overwhelmingly against it, and so few economists think it a good idea. It’s also true that the B-word figures surprisingly rarely in all the discussions about inflation, the labour market, investment, and productivity.

There can be something bogus or contrived about what Maitlis terms “both-sides-ism” and giving equal air time and parity of esteem to individuals talking speculatively, if not nonsensically about the “opportunities of Brexit” (which Brexiteers disagree about anyway – hard vs soft). She doesn’t mention the constitutional stuff about sovereignty and democracy, where the arguments were genuinely more evenly balanced, but we’ll let that pass.

Prime ministers have often loathed the BBC but it is not a good place for the BBC when the politicians’ dissatisfaction is shared by licence payers

Where Maitlis gets it wrong is that the BBC isn’t supposed to be impartial, but rather it’s supposed to be seen to be impartial by those who pay for it – the general public via the licence fee. Impartiality is a will-o-the-wisp, the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, an ideal that can never be secured. It is enshrined in BBC producer guidelines and legislation, but its practical application is dynamic, a matter of day-to-day judgement. It moves around with time.

What would have been an “impartial” discussion about gay rights in 1957 would have been (and was) conducted in very different terms (without even the word “gay”) from how it would be conducted in 2022. The same goes for almost everything. Where once climate “sceptics” were automatically given equal status to the other side, they no longer are. Once upon a time, privatising water and sewage services was thought lunatic; then they were sold off; now it is lunatic again. For many years, when the European question was more or less settled, there was little room for people talking about the fantastical idea of leaving the EU.

I suspect that this reality, that “impartiality” is framed by a kind of wide Overton window of public opinion, is all that Gibb has been trying to impress on his colleagues at the BBC during the various jobs he’s had there. I can see very well why they resented it, but he was trying to do them and the BBC a favour by steering it through such a traumatic episode with minimal collateral damage in terms of its public support.

It was not completely successful because to this day, the likes of Nigel Farage routinely call the BBC biased, Boris Johnson dubbed it the "Bashing Britain Corporation" and Liz Truss says the BBC doesn’t get its facts right. Prime ministers have often loathed the BBC – Harold Wilson, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair especially – but it is not a good place for the BBC when the politicians’ dissatisfaction is shared by licence payers.

Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that the government held a referendum on whether the policy of HMG should be that the world is flat. Now, you might well say, Maitlis-style, that everyone knows the Earth is round (near enough), people who think it is flat are cranks, and believing that it’s flat is anyway against the national interest. She would find chairing a debate between two “scientists”, one pro-flat Earth, the other anti-flat Earth, pointless and irksome (though no doubt conducted professionally).

But if about a third or a half of the British people were devout flat Earthers, distrusted the round globalists and wanted to rebel against the experts and the conventional wisdom, then every bit of BBC output on the subject would have to reflect that reality, even if Emily thinks it’s bonkers. Robbie Gibb was, and is, there to make sure that the cussed, unreasonable, ideological “flag-shagging” Brexiteer licence-payers got to hear what they wanted, as well as the likes of David Cameron and Nick Clegg.

Something of the same goes for the one big mistake Maitlis made in her long and distinguished journalistic career – the intense monologue she performed about Dominic Cummings at the height of the “Barnard Castle” scandal in 2020. It turns out, thanks to an interview Cummings later gave to Laura Kuenssberg, on the BBC, that certain elements of the account he gave in the famous press conference on the Downing Street Rose Garden were wrong. Therefore, some at least of what Maitlis said about Cummings earlier was later proved correct.

She said Cummings had “broken the rules” and “the country can see that, and it’s shocked the government cannot”. All true. But that was not obvious, or proven, when she delivered what amounted to a personal statement, and she was anyway wrong to do so. Presenters aren’t supposed to editorialise. End of. That was why Gibb, and others, acted against her when Downing Street complained.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Maitlis in turn complains of lack of “due process” and is obviously still sore about it. I’ve sympathy. The BBC should treat complaints from prime ministers the same as it would from postmen, by directing them to the relevant forms and Ofcom. As it happens, this is also what should have happened during the Blair government when Alastair Campbell blew up at the BBC about Andrew Gilligan and the Iraq "dodgy dossier”. Things would have been better if it had gone through the usual channels and the programme complaints unit.

That’s not the real world though, and it would have made no difference in the end. Maitlis made an egregious error of judgement. She only needed to let the facts about Cummings speak for themselves; the public hardly needed to be informed that they were angry (an anger shared and openly voiced by many Tory MPs at the time).

Ironically, these American-style monologues are the very thing that GB News and TalkTV do, and her example is used to justify the now widespread abuse of journalistic ethics and the weakening of regulations that protect balance in broadcasting.

The Maitlis monologue also gave substance, however slight, to the persistent myth that the “biased mainstream media” has been gunning for Johnson and Brexit because they hate it so much, and they can’t “move on”. Hence the conspiracy theory that Johnson was “stabbed in the back” by conspirators such as Maitlis.

Of course, the truth is that Johnson was the author of his own downfall, no less than Prince Andrew was when he gave his ill-fated interview to Maitlis for Newsnight. She did a superb job, rightly award-winning, and he made a fool of himself, but his earlier actions were the reason for his fall from grace, not the media. It is a further painful irony that Maitlis’s quietly angry rant about Dominic Cummings should seemingly have played such a part in her gradual detachment from the BBC. Her loss, but also ours.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks