Making A Murderer: Murder cases can enthral all, except the victim’s family

The Netflix show is gripping stuff, but it’s too easy to forget the misery behind the ratings hit

Thanks to Making A Murderer, the latest US hit courtesy of Netflix, the world has murder on its mind. Well, when doesn’t it? Violent crime has sustained drama for centuries, tapping into our fascination with human nature’s sinister side.

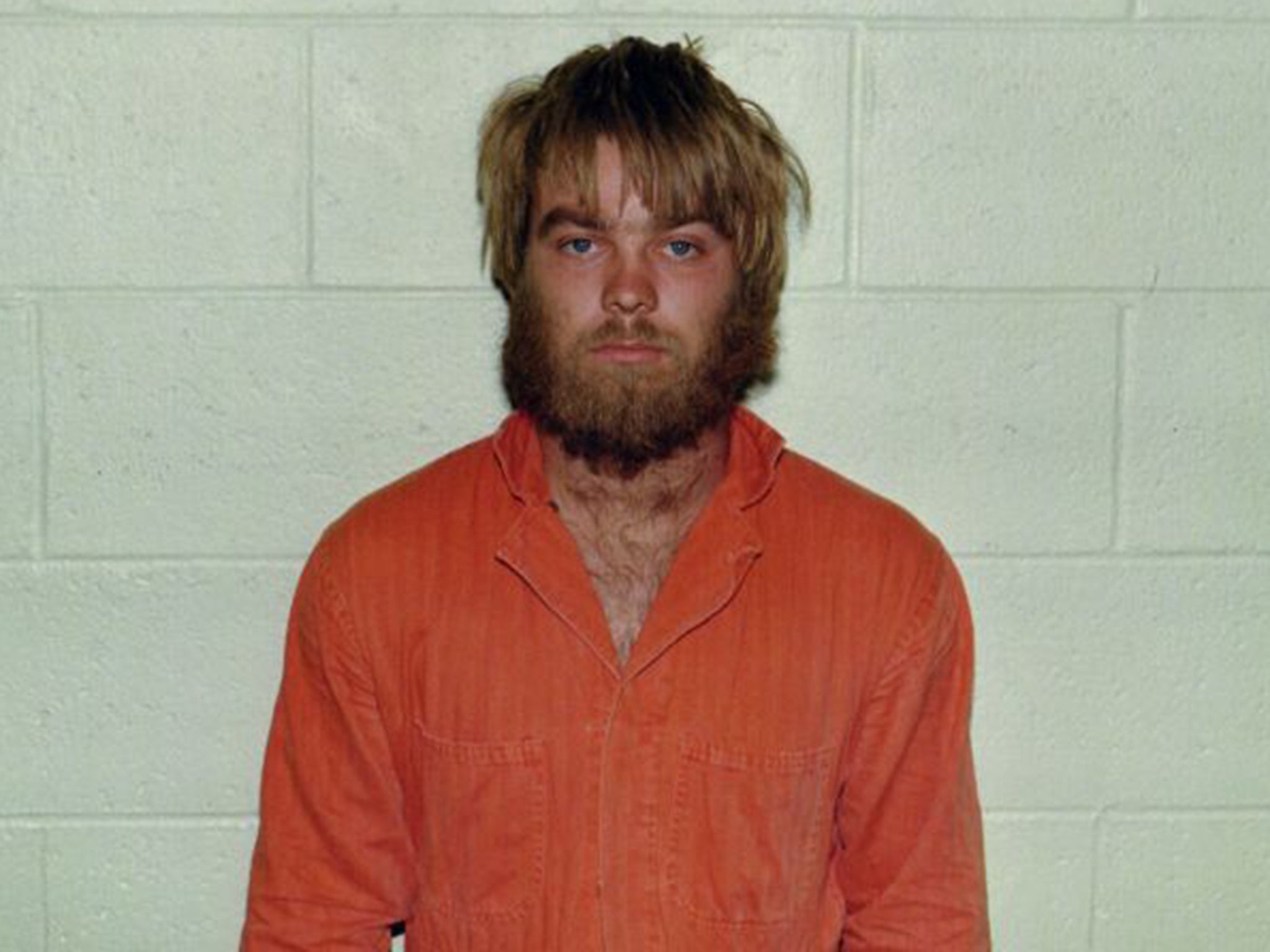

But this series, which looks at the case of Steven Avery who was imprisoned for sexual assault, then exonerated, and then subsequently jailed along with his nephew for the murder of 25-year-old Teresa Halbach, brings with it a new layer of intrigue – that of the true-crime series that dredges up an old case and re-examines the evidence, and makes the audience part of the process.

Making A Murderer made its debut three weeks ago and instantly lit up social media and online message boards as viewers pored over case details and offered their own theories. Affectionately mocking Tumblrs have even appeared devoted to Avery’s defence lawyer, Dean Strang, and his “Seinfeld-era fashion blandness”.

While those behind the series claim impartiality with regard to Avery, Making A Murderer puts forward a clear case of a morally bankrupt judicial system. But amid the speculation and amateur sleuthing, one might ask what the show’s success says about us.

The fever surrounding the series is similar to that of the 2014 podcast “Serial” that re-examined the murder of a young woman, Hae Min Lee, for which her ex-boyfriend, Adnan Syed, was convicted. The series producer, Sarah Koenig, sifted through the evidence and conducted interviews with many of the major players, including Syed. What was assumed to be a niche show became a mega-hit, reaching 75 million downloads. There are also similarities to last year’s HBO mini-series The Jinx, a true-crime documentary about a Manhattan property tycoon who was accused and then acquitted of the murder of a neighbour in Texas, and implicated in the disappearance of his first wife.

While avoiding the sensationalism typical of American network television, Making a Murderer and The Jinx are carefully paced and slickly made. Information is drip-fed, and plot-twists are sporadically lobbed in to maintain the suspense. Also notable are the stylish opening credits and fashionably lo-fi theme tunes, both similar to the fictional murder-mystery True Detective. These are true stories that are, to all intents and purposes, dressed up as fiction. This approach makes it easy to forget that we are watching real lives.

I say this as an avid viewer/listener of these shows. If sitting in my pyjamas pontificating over suspect DNA evidence, shady witness statements and off-kilter timelines is an offence then go ahead officer, bring out the handcuffs. We all like a good criminal yarn, whether it’s terrestrial reruns of Columbo or the shinier, big-budget offerings on subscription television. But, when it involves real victims, we might want to think harder about the ethics of serving it up as entertainment.

Right now, there’s something particularly queasy-making about the viewers who rail against the online spoilers for Making A Murderer. Netflix made all 10 episodes available at once, meaning many are yet to get to the end. Why such fury? Because they want to savour the cliffhangers.

And where do these series leave the victims and their families? In true-crime sagas, the story of the victim is often little more than a narrative footnote since they’re not around to tell their tale.

In the midst of the hysteria over “Serial”, a man who claimed to be the brother of Hae Min Lee posted a message on Reddit – “To me its [sic] real life, to you listeners, its [sic] another murder mystery... I pray you don’t have to go through what we went through.” The family of Teresa Halbach made a similar statement expressing their sadness at the “individuals and corporations [that] continue to create entertainment and to seek profit from our loss”.

Of course, there’s an argument that these series provide a public service, stepping in where the justice system has failed and often gathering new intelligence. Following the first series of “Serial”, and despite no firm conclusions being reached by Koenig, the fight to exonerate Adnan Syed has gathered pace and the Court of Special Appeals has agreed to hear a request for a new trial. A friend of Syed’s, Rabia Chaudry, who launched her own podcast about the case, wrote: “This is not just citizen journalism, this is citizen investigation and crowd-sourced sleuthing.”

Given the noise around Making A Murderer, the plight of Steven Avery and his nephew is unlikely to go away either. A petition has already taken off demanding that the two men be pardoned (to which the Obama administration’s response could be reasonably be summed up as: “You’ve gotta be kidding”).

But as any lawyer would tell us, none of these shows can present all of the evidence from all of the angles since that would make for catastrophically dull viewing. No matter how even-handed their intentions, the film-makers must slash, emphasise and editorialise as they go. Only a partial picture can emerge.

From the Jack the Ripper killings to the death of Meredith Kercher, history has shown us that real-life crime can mesmerise as much as horrify. In the case of Kercher and her alleged assailant, Amanda Knox, there was barely a person in the land who didn’t have an opinion about what happened, proof that you don’t need a documentary series to help you make a sweepingly ill-informed judgement.

These latest crime-dramas are brilliantly executed and hugely addictive, but let’s not kid ourselves. A nation of detectives we are not. More importantly, one person’s nail-biting whodunnit is another’s person’s terrible tragedy. The people in these stories exist and these things really happened. We’d do well to remember that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks